In 2010, the relatives of Spanish and Argentinian citizens killed at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) by Francoist forces filed a complaint in Argentina for the crimes of the Spanish dictatorship. The unprecedented decision was symbolically charged: it was announced on April 14, the anniversary of the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, which Franco’s coup overthrew in 1936, in the presence of Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Argentinian human rights activist and recipient of the 1980 Nobel Peace Prize, and Nora Cortiñas, President of Argentine relatives’ association Madres de Plaza de Mayo. With the support of human rights lawyers Carlos Slepoy and Ana Messuti, both longtime residents in Spain after being exiled from their native Argentina, the plaintiffs launched what became a criminal case, “Case 4591/10 on charges of genocide and/or crimes against humanity committed in Spain by the Franco dictatorship between July 17, 1936 and June 15, 1977”. The case, commonly known as the Argentinian Complaint (querella argentina), is being instructed by Judge María Servini de Cubría in the Federal Criminal and Correctional Court No.1 in the Argentinian capital Buenos Aires. Without knowing it, the plaintiffs also initiated a process that would redefine the struggle for the recovery of historical memory that had emerged in Spain in 2000.

The Argentinian Complaint, the only case open in the world to prosecute Franco’s crimes

The struggle of Franco’s victims gained momentum throughout the 2000s, and in 2007 the so-called Historical Memory Law was approved by the Spanish Congress. Introduced by the Socialist Party, the Law was criticized by opponents and advocates of the recovery of historical memory alike. For the former, the Law reopens old wounds that Spain chose to heal when it adopted its Amnesty Law in 1977. As for Franco’s victims and their relatives, they complained that it provides only limited reparations, that it merely encourages local authorities to remove Francoist symbols from public spaces and to provide assistance with the exhumations of the graves of the Civil War and the dictatorship, and that it does not annul the sentences handed down by illegitimate Francoist tribunals. Right-wing local authorities, but also many of those governed by the left, have not implemented the Law. Besides, following their return to power in 2011, conservatives cut funds for the recovery of historical memory and closed down the unit in charge of overseeing the implementation of the 2007 Law.

On the other hand, many associations and individuals wanted Franco’s crimes to be judged by the courts. Several complaints had been filed throughout Spain since December 2006, and in 2008 Judge Baltasar Garzón declared himself competent to investigate Franco’s crimes. The following year, he was accused of abusing his authority. Two more cases were subsequently opened against him and in February 2012 Garzón was suspended for illegally wiretapping conversations in one of them, a corruption case. A few weeks later, the Spanish Supreme Court acknowledged a right to memory for Franco’s victims but defined it as a purely private matter. Garzón’s earlier suspension and the Supreme Court’s decision were perceived as the definitive burial of historical memory and justice for Franco’s victims in Spain. As a result, the Argentinian Complaint is the only case open in the world to prosecute Franco’s crimes. The remainder of the article explains how a growing number of victims’ and relatives’ associations have since then joined the first plaintiffs and redefined the significance of the Argentinian Complaint.

Human rights activism across borders and the broadening of historical memory

Franco’s victims have invoked the principle of universal jurisdiction for crimes against humanity to seek justice in Argentina. This might seem paradoxical insofar as the crimes of several Latin American dictatorships were investigated in recent years in Spain, leading the government to repeal the universal jurisdiction law in 2014 after a court ordered the detention of several Chinese leaders for the repression in Tibet. Some cases however continue, under other principles such as citizenship links between Spain and victims or perpetrators in or from Latin America. While Garzón sought to investigate the crimes committed in Spain between 1936 and 1951, the time frame of the Argentinian Complaint is much wider since it encompasses the period between July 17, 1936, the date of the right-wing Nationalist uprising that provoked the Civil War, and June 15, 1977, the date of the first democratic elections after Franco’s death in 1975. Spain’s Amnesty Law covers all crimes “of a political nature” committed prior to December 1976, but it is estimated that more than 180 individuals were killed by security forces or paramilitary groups linked to the state between 1975 and 1983. As the number of complaints filed in Argentina kept increasing, a National Coordination Group in Support of the Argentinian Complaint (Coordinadora Estatal de Apoyo a la Querella Argentina, CeAQUA) was created in Spain in May 2013. It has been very active in Spain and abroad, taking its members’ cause to institutions such as the Spanish Congress and the European Parliament.

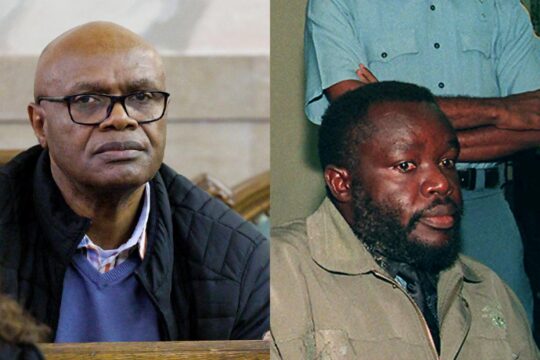

The Argentinian Complaint created an opportunity for victims of repression during the second, supposedly less violent, part of the Spanish dictatorship to acquire visibility. In addition to Spaniards in exile and former prisoners, complaints have been filed by thousands of individuals who suspect that they or their biological children, who were pronounced dead at birth, are in fact some of the babies who were stolen from their parents in maternity wards over the course of various decades. Complainants also include victims of the Vitoria massacre of 1976 and their relatives, in which the police repressed a general strike, killing five workers and injuring dozens of demonstrators. The perpetrators of these crimes have never been brought to justice. One of the most notorious suspects is Rodolfo Martín Villa, a politician who served in various cabinets under the dictatorship and was Minister of the Interior between 1976 and 1979. Judge Servini accuses him of ordering the Vitoria massacre. Protected by the Amnesty Law, Martín Villa sat in the Madrid local assembly between 1989 and 1997, and until 2010 chaired various companies, including Spain’s major electric utility company ENDESA. By requesting the extradition of these individuals, Judge Servini has put the spotlight on the plight of victims and their relatives as well as on the scope of impunity and its consequences in Spain.

Documentary about the Vitoria massacre

Documentary about Spain’s stolen babies

The achievements of the Argentinian Complaint

Judge Servini issues the first arrest warrants in Argentina against former members of the Spanish dictatorship (September 2013)

Since the Argentinian Complaint was launched in 2010, almost two hundred complaints have been filed. More will undoubtedly follow. The extradition of more than 20 individuals has been requested. Yet Spanish courts and the government have refused to collaborate with Argentinian justice. Nevertheless, it should not be concluded that the efforts of Franco’s victims and their relatives have been in vain. Although perpetrators still enjoy impunity, Spaniards now know that the repression carried on even after Franco’s death. Likewise, while only a handful of Spaniards knew about the Vitoria massacre just a few years ago, as a consequence of the process set in motion in Argentina, this and other previously little-known aspects of the repression have received more attention [see Info Box]. Even if it cannot replace justice, truth remains essential to memory-making.

|

Info Box: groups of victims represented by the delegates of CeAQUA’s delegation that traveled to the European Parliament in March 2015 |

|

|

José María ‘Chato’ Galante and Luis Suárez Carreño |

Former prisoners and victims of torture |

|

Paqui Maqueda |

Relatives of victims of forced disappearance |

|

Merçona Puig Antich |

Sister of anarchist activist Salvador Puig Antich who was sentenced to death by a military court for allegedly firing the shots that killed a Civil Guard in an operation aimed at detaining anarchist activists. Despite much opposition to the sentence in Spain and abroad, in 1974 he was the last person executed by garrote by the dictatorship. |

|

Soledad Luque Delgado |

Stolen children |

|

Elsa Osaba |

Spaniards in exile, victims of deportation and their relatives |

|

Josu Ibargutxi |

Victims of the Vitoria massacre and their relatives |

|

Irene de la Cuerda |

Victims of forced labour |

In fact, the growing visibility of these various episodes and forms of past repression also reflects the emergence of new actors within the movement for the recovery of historical memory. An association of former prisoners, La Comuna, and several associations of relatives of the stolen babies, played a crucial role in the creation of CeAQUA. Some of these associations are relatively recent, and they have remained at the forefront of the struggle of Franco’s victims. By creating an opportunity to obtain justice, the Argentine Complaint has been instrumental in uniting a range of actors and pooling their efforts, which has given the wider movement a new momentum. Moreover, although the Spanish Second Republic and its political project remain important elements in the movement’s discourse, the Argentinian Complaint has facilitated a growing role of international law in both the strategy and discourse of the movement for the recovery of memory, illustrating the extent to which international law can be a powerful tool for domestic social movements.

It remains to be seen whether the emergence of new actors, combined with the adoption of a new language that has been successful in boosting the legitimacy of similar struggles elsewhere, might help to advance the cause of Franco’s victims at home. Spain is unlikely to come to terms with her past as long as conservatives and those politicians who were involved in the transition to democracy are in power. But Spanish activists have already demonstrated that the passing of time, an amnesty law and state-sponsored amnesia may not tame memory and the demand for justice.