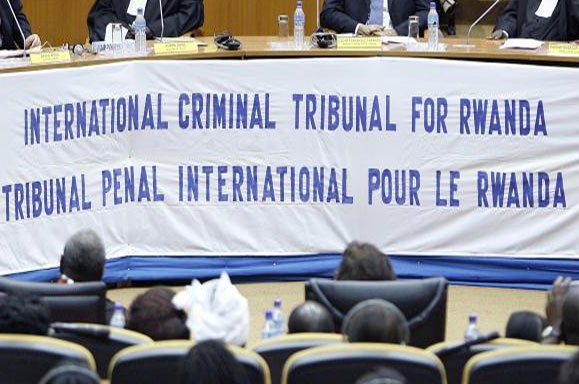

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), which has officially closed its doors and handed down its last judgment after some 20 years of work, is a bit like the United Nations that set it up after the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. It was costly, slow and much criticized, but also ground-breaking, precedent-setting and necessary. But was it independent, as international justice claims to be? Can justice ever be independent of politics?

The ICTR was only the second international tribunal (after the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia, ICTY) with a mandate to try international crimes after the Nuremberg trials at the end of the Second World War. It has helped forge international justice and combat impunity. Its vast jurisprudence is an important legacy, especially on genocide and the prosecution of sexual crimes.

At the heart of its work was its relationship with Rwanda, which was not easy. The ICTR was criticized, first of all by Kigali, for being outside Rwanda, far from the victims of the genocide. It was created against a background of a new, mainly Tutsi government in Rwanda, representing the ethnic group of genocide victims, and Western guilt at having done little or nothing to stop the genocide. Being outside Rwanda in Arusha, Tanzania, it relied on cooperation from Kigali to bring Rwandan witnesses to testify in its cases.

Most observers agree that the ICTR’s work has been important. The main criticism is that it only prosecuted crimes of genocide by the predominantly Hutu government and not alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity by the predominantly Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) which won the war and has been in power in Kigali since July 1994.

The ICTR was set up under UN Security Council Resolution 955, which gave it a mandate to hunt down and bring to justice those most responsible for “genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of Rwanda, and Rwandan citizens responsible for genocide and other such violations committed in the territory of neighbouring States, between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994.”

The mandate limits the Tribunal’s jurisdiction to 1994, so it could not go after alleged Rwandan crimes in subsequent years, such as 1996 in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo. But the Tribunal’s mandate was not restricted to genocide, it also included “other serious violations of international humanitarian law”.

No prosecutions of the RPF

“Choosing to focus on prosecuting and trying the authors of the genocide was justified in the conditions that were those of the ICTR when it was set up, as well as a duty towards the victims and survivors,” French sociologist André Guichaoua, who has testified as an expert in several ICTR trials, told JusticeInfo.net in late 2014. “But the fact that successive Prosecutors subsequently bowed – with the blessing of the UN Security Council – to the refusal of the military men in power (in Kigali) to have the whole of the Court’s mandate carried out has weakened its credibility and the scope of its judgments, truth telling and most certainly the appeasing of passions and controversies between parties to the conflict,” he said. “So the task given to the ICTR has not been completed,” added Guichaoua, in reference to crimes allegedly perpetrated by members of the ex-rebel RPF.

Géraldine Mattioli-Zeltner of Human Rights Watch, an NGO that helped spearhead the creation of the ICTR, says this is “perhaps the greatest failure of the ICTR”.

“Not a single case concerning these crimes was brought before the court,” she told JusticeInfo.net, “despite the fact that it has a clear mandate to also prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the RPF in 1994. These crimes cannot at all be equated with the genocide, but the victims also have a right to justice. The ICTR’s reticence to try RPF crimes can be explained by strong pressure from the Rwandan government and the risk that it would jeopardize the government’s cooperation in other cases. Nevertheless, the failure to try RPF crimes is a stain on the Tribunal’s legacy. It creates the impression that the ICTR handed down victor’s justice, and undermines its credibility, notably with the Rwandan population, the main people the Tribunal was meant to serve.”

The only ICTR Prosecutor who looked as if she might go after the RPF for its alleged crimes during the war, Carla Del Ponte of Switzerland, was removed from the job under pressure from Kigali.

Also, the ICTR never really looked into the downing of the late ex-president Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane over Kigali on April 6, 1994, the event that triggered the genocide. “It does not fall under our mandate,” current Prosecutor Hassan Bubacar Jallow repeatedly told reporters. And yet, there were some investigations. The late Australian ICTR investigator Michael Hourigan (he died of a heart attack in 2013), working under a mandate from Prosecutor at that time Louise Arbour of Canada, said he had submitted first-hand witness testimony to the Tribunal that current Rwandan President Paul Kagame ordered the downing of the plane but that his report had been suppressed by Arbour.

Dependence on Rwandan cooperation

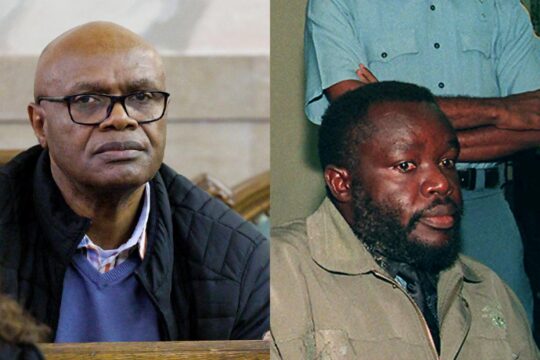

A striking example of the Tribunal’s dependence on Rwandan cooperation (and a major low point in their relations) came in November 1999, when the ICTR Appeals Court in The Hague ordered the release of Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, propagandist for the regime that presided over the genocide, leader of the extremist Hutu CDR party and chairman of the executive committee of Radio-Télévision des Mille Collines (RTLM), the notorious radio that incited genocide. The ICTR Appeals Court ordered his release on grounds of violation of his rights. The ICTR had been too slow, had not respected the rights of detainees, the Court said. It was a warning to the ICTR. But Rwanda was incensed. It suspended cooperation with the ICTR and said no more witnesses would be coming. That would basically mean the ICTR was dead.

Normally, an Appeals judgment cannot be reversed, unless “new facts” are brought as evidence. So, faced with this situation, the ICTR Prosecutor at the time (Carla Del Ponte) went out of her way to present some. The decision was reversed and Rwanda resumed cooperation with the ICTR. Barayagwiza was never released. He declared himself a political prisoner of the UN and boycotted his trial, was convicted in absentia and died of illness in prison in Benin in 2010.

Another problem was faced by the defence. Some defence teams feared to go to Rwanda for security reasons, so gathering evidence was difficult, and this gave the prosecution another de facto advantage.

British lawyer Stephen Kay, counsel for former tea factory boss Alfred Musema, was the first ICTR defence lawyer to go to Rwanda in 1999. It opened a door for other defence teams, although it was still not clear that prosecution and defence had equal possibilities to gather evidence.

The validity of the ICTR’s work, its judgments and its contribution to international justice are not in question, but observers think these issues of independence and balance somewhat tarnished the Tribunal’s image. “It is also important to remember what worked less well, so as to improve the functioning of this type of tribunal in the future”, Géraldine Mattioli-Zeltner of Human Rights Watch recently told JusticeInfo.net.