The news didn’t make a big splash in the international media, despite the person’s stature. Enoch Ruhigira, who was the last head of presidential staff under Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana, was arrested in July in Germany on the basis of a Rwandan arrest warrant accusing him of crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity committed between 1990 and 1994. The Hutu former dignitary is being detained on the basis of accusations which were found to be baseless in New Zealand, the country where he had citizenship, and Belgium, where he had also spent some time.

It was mostly the Rwandan media that picked up the news. According to the blog News from Kigali in Brussels (Les Nouvelles de Kigali à Bruxelles), Enoch Ruhigira “was living quite openly for more than 20 years”, without changing his name or his appearance, and without the protection of any foreign power, even if the online newspaper Igihe reminded readers that Belgium had facilitated his flight into exile on April 12, 1994.

The News from Kigali in Brussels blog goes on to say that according to certain allegations, Enoch Ruhigira “had been approached to join the new regime straight after the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) rebels took power in July 1994”.

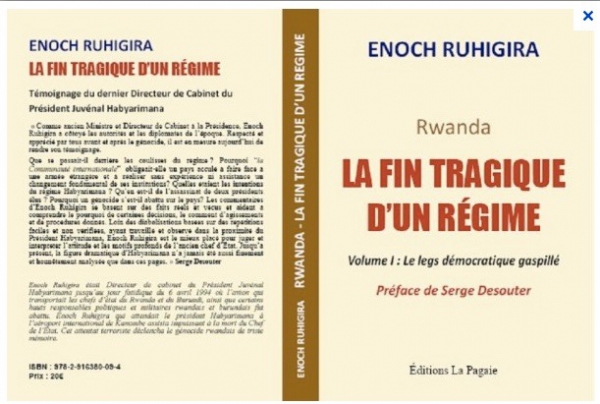

In 2011, he had published Rwanda: the tragic end of a regime, in which he offered a different interpretation of the Rwandan 1990-1994 tragedy. The book encourages a more nuanced approach to, or categorically casts doubt on, certain statements that are often presented as facts or public knowledge. Thus the author denies that France blindly supported President Juvénal Habyarimana and suggests that the Tutsi businessman and leader Landouald Ndasingwa, who had been a member of the transitional government, could well have been killed at the start of the genocide not by the government army but by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) “as he was beginning to grow tired of RPF interference” in his own political group, the Liberal Party (PL).

“There could be a link between his decision to testify through this book, as well as through other channels, and his recent problems with the justice system”, speculates News from Kigali in Brussels.

Head of Habyarimana’s presidential staff

Now aged 65, Enoch Ruhigira, an agronomist by training, is from Bwakira district, in the former Rwandan prefecture of Kibuye. Many testimonies, including that of the then Belgian ambassador in Kigali, Johan Swinnen, confirm that Enoch Ruhigira did not accompany his boss, Juvénal Habyarimana, to the summit in Dar-es-Salaam on April 6, 1994, the day of the attack which killed the head of state after a missile hit his plane as it was preparing to land at Kigali international airport that evening. Habyarimana had asked him to start negotiations with Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana that same day on steps towards establishing transitional institutions as soon as he returned.

The day after the attack, according to Johan Swinnen, Enoch Ruhigira managed to take refuge in the residence of the Belgian embassy, whereas other senior dignitaries from the presidential party, the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND), sought refuge in the French embassy, escorted, in some cases, by elements of the Presidential Guard.

When the interim government was set up on April 9, 1994, Enoch Ruhigira, who was still staying at the Belgian diplomatic representation, was reappointed in his absence to his old post as chief of staff of the president’s office, with Théodore Sindikubwabo as president. But Ruhigira would never take up this post under Sindikubwabo, because on April 12, 1994, the Belgian army evacuated him to Nairobi, and from there he travelled to Belgium.

One month later, President Habyarimana's former close aide had still not turned up to see his new boss Théodore Sindikubwabo. In an official telegram dated May 13,1994, delivered two days later by the foreign affairs ministry, Sindikubwabo instructed the Rwandan embassy in Nairobi “to contact Mr Ruhigira Enoch, chief of staff of the president’s office” and “ask him to come to the [president’s] office immediately.” The embassy also received an order to “facilitate his travel to Kigali”.

But Enoch Ruhigira would never turn up, and the interim government had to replace him with Daniel Mbangura, another member of the MRND party.

Red notice

As soon as the genocide ended in July 1994, names of officials of the former regime suspected of having played a role in the preparation or implementation of the genocide were published in the media and in reports by non-governmental organizations. Enoch Ruhigira’s name did not appear anywhere. The new Rwandan government published its own list of suspects, which was revised several times, but Enoch Ruhigira’s name did not feature in that list either.

In 2004, Interpol issued a “red notice” at Rwanda’s request, but it was not until May 2006 that Enoch Ruhigira’s name appeared for the first time on the Rwandan list “of people suspected of having committed genocide and living outside Rwanda”.

How could the possible involvement of such a senior figure have escaped the attention of investigators at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the Rwandan justice system for so long? Probably intrigued by this question, the authorities in New Zealand carried out further investigations of their own.

In 2007 and 2009, the different strands of information gathered in the New Zealand and belgian procedures invalidated all the alleged accusations. When he heard about the existence of an Interpol red notice against him, Ruhigira himself protested his innocence and asked that the arrest warrant be cancelled. And on April 15, 2014, the New Zealand minister responsible for immigration informed Ruhigira – a citizen of New Zealand – of the result of their investigation. “The result of the investigation is that there is nothing linking you directly to the planning of or involvement in the genocide.”

Over the last few years, Rwanda has not filed any formal extradition request to Interpol and the “red notice” was withdrawn. Indeed Enoch Ruhigira and his wife travelled to Australia in December 2015, then to the Philippines in January and February 2016, without encountering any problems. So in June 2016, they bought tickets to spend their holiday in Europe.

That was when the pro-government Rwandan newspaper The New Times announced on July 1 that the public prosecution authorities in Kigali had issued two sets of charges against people suspected of involvement in the genocide who were living as refugees in New Zealand. On July 19, as Enoch Ruhigira was on a plane to Europe, the prosecution authorities in Kigali made public the names of the two accused: “They are being prosecuted for genocide and crimes against humanity. (Eugène) Uwimana committed the crimes in Butare, particularly at the UNR (National University of Rwanda) whereas Ruhigira was in Kigali,” Nkusi, the spokesperson of the National Public Prosecution Authority, explained to The New Times.

On July 26, the same Rwandan daily announced the arrest of Enoch Ruhigira in Frankfurt six days earlier, quoting the spokesperson of the public prosecuting authority again: “We received the official information on July 22 from Interpol. We are now preparing official extradition documents to be submitted in Germany to the General Prosecutor’s Office by October 19.”

Questions

As a plethora of policemen were mobilized at Frankfurt airport to arrest “one of the most important Rwandan genocide suspects” on the run for more than 20 years, a few questions should be asked.

First of all, there are questions of procedure: on what legal basis could the Frankfurt prosecuting authorities arrest and detain Enoch Ruhigira, like a major criminal, when he was just in transit, in the absence -- as it turned out later -- of any arrest warrant or Interpol notification?

On what information did the Frankfurt border police and prosecuting authorities base their “presumption” of guilt when when during a first stopover in Singapore, a few hours before he reached Germany on a Lufthansa flight, Singapore airport authorities had given him an entry visa to the spend the day of July 18-19 in Singapore without finding anything on the Interpol website? Just as the Australian and Philippines authorities had done a few months earlier.

In formal terms, it appears to be a proprio motu decision by the prosecuting authorities of Frankfurt which would have taken the initiative itself to transmit for approval in the authorities of Kigali the arrest warrant of 2004 found in the archives of the German police. An opportunity at hand, in a way that Rwanda could not refuse … or an affirmative answer to the prosecutor's department of Kigali which had announced the emission of new mandates to Rwandans living in New Zealand when he learnt that Enoch Ruhigira was going to move in Europe?

Furthermore, why did the Frankfurt prosecuting authorities immediately ask the public prosecuting authorities in Rwanda to send through a provisional warrant and put together an extradition file, apparently without asking Interpol about any history of previous documents which either did not exist or had been withdrawn? Why, from the outset, did they impose on the suspect, presuming him guilty, a long and harsh period of incarceration without asking the authorities of the country of which he is a citizen how he could benefit from such unlikely impunity for so many years, despite the very serious crimes of which he might be accused? New Zealand’s outstanding international reputation in terms of rule of law and democracy should have meant that the Frankfurt prosecuting authorities could consider it, from the outset, as legitimate and credible an interlocutor as Rwanda.

Then, there are questions of substance. How can such serious crimes attributed to a prominent figure -- who, what's more, never even tried to hide or to conceal his real identity -- remain unknown to the international public for so long, without any independent investigator or any expert witness, including those who testified to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), ever involving the former chief of presidential staff in their investigations into the 1990-1994 Rwandan tragedy and prosecutions that have taken place since?

Will the Frankfurt prosecuting authorities therefore extradite Ruhigira to New Zealand, where the case is already closed? If he is tried by the German justice system, what kind of justice will he receive in a country which rushed to arrest him, blindly executing a virtual arrest warrant, on accusations that were found to be baseless and were rejected by all the foreign administrative and judicial authorities who have had to consider them so far? Anyone facing criminal accusations has the right to know why they have been arrested and the precise accusations against them.

It is disturbing enough that a public prosecutor arrests a passenger in transit, in anticipation of an extradition process towards a country which has not issued an arrest warrant. Even more concerning is the fact that the German authorities are now detaining someone for at least three months to enable Rwanda to draw up an indictment which it has failed to define twenty years after the alleged crimes.