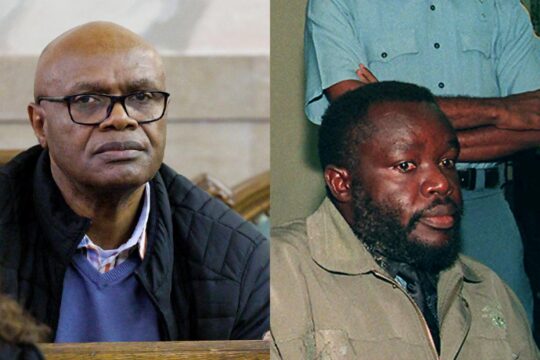

After two trials and nearly three years, the appeals court in Bobigny (Paris area) reached the same conclusions as the lower court in Paris on former intelligence agent Simbikangwa’s role in the 1994 genocide, during which many Tutsis were killed on roadblocks. “Pascal Simbikangwa gave arms and instructions to the people manning some of these roadblocks, knowing that the victims were Tutsis and civilians,” declared presiding judge Régis de Jorna, quoting the December 3 judgment. This came despite the vehement denials of the accused and the fragility of some testimonies given 22 years after the events.

In their six-page reasoning, which is less detailed than the first judgment, the twelve appeals jurors (three professional and nine non-professional) confirmed Simbikangwa’s conviction for genocide and complicity in crimes against humanity. “His closeness to the presidential circle (of former President Habyarimana) and his reputation meant he was assumed rightly or wrongly to be part of the so-called Akazu, composed of political and military figures close to the president accused of having extremist views and having carried out abuses in the name of the extremist ideology.” Evidence of his participation in arms distribution and his presence on the roadblocks rests, according to the written decision, on the testimonies of three security guards who worked at or near his residence. Three other witnesses also testified to the presence of weapons at his house.

“Not a foregone conclusion”

“It was not a foregone conclusion once we heard the defence pulling the testimonies apart one by one,” said a relieved Alain Gauthier, president of the Collective of Civil Parties for Rwanda (CPCR), which helped bring the case. Gauthier, who has followed both the lower court and appeals court trials, admits that some testimonies had “certain weaknesses”. He thinks the appeals trial brought nothing new. “We could have done without it,” he said the day after the verdict. “Hearing the same nonsense, the same Simbikangwa as he was before, it forces us to go through things that we do not want to relive. I admit that these appeals trials are very wearing for us, the CPCR and the victims.”

“A botched decision”

Following this second verdict, Simbikangwa’s defence lawyers announced their intention to go to the Supreme Court. “It is a botched decision unworthy of the French judicial system,” complained lawyer Fabrice Epstein, adding that he did not understand “how after six weeks of debates you can hand down such a thinly reasoned verdict in four hours backing the theory that if you were in Kigali between April and July 1994 you must be guilty of genocide.” For him and Alexandra Bourgeot, who defended Pascal Simbikangwa in both his trials, it is a failure for their efforts to systematically undermine the credibility of the 50 witnesses presented for the appeal.

Epstein thinks none of the testimonies used to back the conviction are credible. “Either they were alone, or they were not corroborated, or they contradicted themselves,” he says. “We have got the same result (as in the first trial) but the reasoning is very, very vague. The only development is that the jurors were not convinced by certain incidents. That is perhaps down to the work of the defence.”

“A fair judgment”

The civil parties see things quite differently. “We had two very different trials, one in Paris and one in Bobigny, with very different judges and jury,” commented CPCR lawyer Simon Foreman. “If the decision was the same, it means it is right, and it remains right.” He sees it as a sanction against the defence strategy of “negating everything, accusing absolutely everyone of lying as soon as there is the slightest comma of difference between what a witness said at one time and what he said at the hearing”. This strategy, according to Foreman, “only highlighted Pascal Simbikangwa’s own lies on everything. At the beginning of the investigation he said he was in the countryside during the genocide, and then he said he was in Kigali. If there was someone who was not consistent in their declarations, it was him.”

There is still frustration for the victims, according to the CPCR lawyer. “The victims always dream of the accused making confessions, apologising and explaining, which would help make sense of what happened. We did not get that, which is not necessarily surprising, but it is a shame.”

Just the beginning

With this verdict in the Simbikangwa case and the July 6 conviction of two Rwandan ex-mayors by a Paris court, 2016 has been a busy trial year for France’s special crimes against humanity unit. It currently has some 15 investigations under way on Rwandan genocide suspects residing in France. Some of these are expected to be completed in early 2017, with new trials likely in 2018.

This should therefore be just the start of Rwandan trials in France under the principle of universal jurisdiction. But there is the risk of a logjam for these long and costly trials. At the specialized unit, magistrates are considering joint trials so as to limit costs and keep to deadlines. However, the French system of the appeals court – composed of twelve appeals jurors (of which nine non-professional) -- will always mean Rwandan trials spending the first half of hearings on explanations of the Rwandan context, often by the same experts. Professionalizing the jury, which is proposed by some, could speed things up by several years. But it would require a change in the law which, according to sources close the special unit, is not on the cards.

“Now the focus is not political will but practical feasibility for the unit,” says Simon Foreman. “I do not know how relations between France and Rwanda will develop. Are we going into a new period of slowdown? I hope not, but it is possible.”