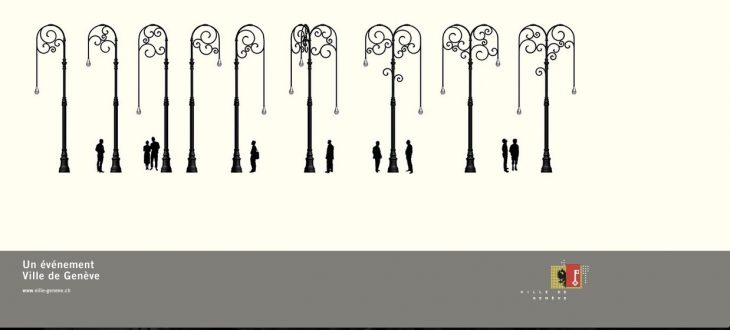

After long years the “Streetlights of Memory”, a work by French artist Melik Ohanian, found a home in Geneva on April 13. It first needed the Geneva parliament in 1998 and then the Swiss parliament in 2003 to recognize the Armenian genocide.

It then required the determination of those defending remembrance, the City of Geneva and especially the Municipal Fund for Contemporary Art (FMAC) to get a monument selected that evokes the Armenian genocide and the evil that man can inflict on man. Finally, the promoters of the monument had to overcome the reservations of several parties, often linked to fear of upsetting the Turkish authorities. Istanbul, which still refuses to recognize the Armenian genocide, made known its fierce opposition. But isn’t the history of every country made up of good and bad times?

It is a good thing that Geneva and Switzerland have given a home to the “Streetlights of Memory” because, like every tragedy, the Armenian one needs to be remembered. This is all the more necessary because denial remains strong. Let us remember that in October 2015 Switzerland was sanctioned on appeal at the European Court of Human Rights for infringing the freedom of expression of a Turkish politician who had denied the existence of the Armenian genocide.

Treaty of Lausanne

The Armenian tragedy should make us reflect, because it was a precursor to events that followed in the 20th century and right up to now, especially the persecution of minorities and policies of ethnic cleansing, under the often indifferent eyes of the cold monsters that are States. The big colonial powers of the time, France and Britain, divided up the spoils of the Ottoman empire in the Middle East (Sykes-Picot accords of 1916), whilst not far away hundreds of thousands of men, women and children were being deported and killed. In this sea of misery there were nevertheless some bright spots – the development of refugee protection and international humanitarian law. In other words, the Armenian genocide and its aftermath are inseparable from the history of Switzerland and the modern world.

It was on Swiss soil that key decisions were taken, drawing the map of Turkey today after the massacres of Armenians in 1915-1916. In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne, negotiated at Ouchy Castle, satisfied the government of Kemal Ataturk by refusing to create an Armenian state in the northeast of present day Turkey. Such a state had nevertheless been promised by the winners of the First World War in the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. But the Treaty of Lausanne overruled the Treaty of Sèvres.

It was also the Treaty of Lausanne which, in the wake of broken promises to the Armenians and Kurds, forced population exchanges between Greece and Turkey. More than 1.5 Ottoman Greeks and nearly 400,000 Greek Muslims, with the “knife to their backs”, had to leave their respective homes for a supposed motherland that they had never known. Thus the big powers of the time allowed the Armenian genocide to happen and then backed a policy of ethnic cleansing such as we have continued to see in the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s and very recently in the ongoing persecution of different minorities in Syria and Iraq, including the Yezidis.

On a more positive note, it was in Geneva that in 1924, the now defunct League of Nations – whose headquarters was only a few hundred metres from the “Streetlights of Memory” – gave a form of international protection, the Nansen passport, to stateless persons and Armenian survivors, to facilitate their quest for an asylum country. Some found a home in Switzerland.

Hitler and the Armenians

It was also from the spilled blood of Armenians that international humanitarian law, so close to the hearts of Geneva and Switzerland, developed to tackle a new and monstrous reality of war: the fact that civilian populations had become a target for annihilation. Indeed, after the massacres of Armenians had started, France, Britain and Russia denounced in a 1915 joint declaration a “crime against humanity and against civilization”. Apart from one speaker at the 1794 Paris Convention who called slavery a crime against humanity, this was the first time that concept had been so clearly affirmed.

But even if the western powers and Russia at the time denounced the massacres of Armenians, they did not intervene. This led Adolf Hitler to say on August 22,1939, just days before the invasion of Poland : “Who remembers the massacre of Armenians now?”. Speaking to the German high command, he encouraged his generals to treat the Jews and Slavs in the eastern territories the Nazis planned to conquer with extreme brutality, promising them total impunity which he thought was guaranteed by the world’s passivity towards the massacres of Armenians.

It was Polish jurist Raphaël Lemkin, comparing in his book Axis Rule over Occupied Europe the world’s failure to assist the Armenians in 1915-1916 and Jews in the Second World War, who coined the term genocide (derived from the Greek word genos for race, and the Latin word cide, meaning to kill). He wanted to capture both conceptually and in legal terms a new, monstrous reality of war -- the extermination of civilian populations --, so as to better fight it. Lemkin was also the tireless architect of the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Tragically, neither international law nor the lessons from the Armenian genocide a century ago have provided a sufficient guarantee against new horrors. We know this all too well, as millions of Syrians and Iraqis continue to suffer a pitiless war without end.

The “Streetlights of Memory” invites us to make the link between the Armenian tragedy a century ago and the tragedies of the present, sometimes in the same places where so many Armenians died.