On December 7, 1972, the crew of Apollo 17 was 45,000 km from Earth. The three astronauts had the sun behind them and were heading for the Moon, where they were going to land. It was then they took the first photo of our planet. Earth looks like a blue marble that children play with. And so the first image of Earth was called the Blue Marble. This iconic photo marks a turning point in the development of our ecological awareness. For the first time, the Earth appeared at the same time unique, beautiful, fragile and vulnerable, a tiny point in the infinite universe.

Awareness has grown slowly but gradually of the need to protect it, and so also to protect life, against the damage caused by mankind. The link between environmental rights and human rights has been better established and proven scientifically, but politics and economics have hardly taken this into account. It was only in September this year, i.e. four decades later, that the Prosecutor’s office at the International Criminal Court (ICC), in a document full of judicial precautions (“this document does not give rise to legal rights, and is subject to revision”) entitled “Policy Paper on Case Selection and Prioritisation”, evoked the crime of ecocide, without actually naming it. This term is formed from the prefix eco meaning home or habitat (oikos in Greek) and the suffix -cide meaning to kill (caedo in Latin).

The ICC prosecution's new policy document states that it will now give particular consideration to prosecuting Rome Statute crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes) "that are committed by means of, or that result in, inter alia, the destruction of the environment, the illegal exploitation of natural resources or the illegal dispossession of land". It says the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) “will also seek to cooperate and provide assistance to States, upon request, with respect to conduct which constitutes a serious crime under national law, such as the illegal exploitation of natural resources, arms trafficking, human trafficking, terrorism, financial crimes, land grabbing or the destruction of the environment”.

And so the concept of ecocide, first debated by the UN’s International Law Commission in 1947 (!) as a potential crime against the peace and security of humanity, has finally been given a legal expression. However cautious the OTP’s wording is, it represents a small victory for NGOs and all those who have been fighting for years for an international legal framework to punish environmental crimes.

Gillian Caldwell, director of NGO Global Witness, which has been in the forefront of this fight, sees this as a sign that “the age of impunity is coming to an end. Company bosses and politicians complicit in violently seizing land, razing tropical forests or poisoning water sources could soon find themselves standing trial in The Hague alongside war criminals and dictators. The ICC’s interest could help improve the lives of millions of people and protect critical ecosystems”. As an activist, it is natural for Gillian Caldwell to be resolutely optimistic, even if she is perhaps overly so.

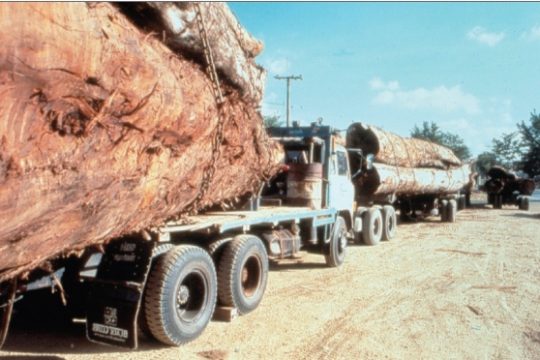

According to Global Witness, millions of people in the developing world have been chased from their land illegally and often violently in countries that do not have an independent justice system. Still according to this NGO, in 2015 more than three people were murdered a week defending their land from theft and destructive industries. “Conflicts over mining were the number one cause of killings, followed by agribusiness, hydroelectric dams and logging,” it says.

Law firm Global Diligence has already filed a request to the ICC on behalf of 10 Cambodians, asking it to investigate massive land-grabbing for profit by the government and army in Cambodia, as a crime against humanity. Some 350,000 people in Cambodia have thus been forcibly evicted from their land since 2002, says Global Diligence. According to its argument, land-grabbing is not a crime against humanity in itself, but if it leads to forcible transfer of population on a large scale it can be considered one and thus fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC.

Given the ICC’s 15-year track record, it is likely that the Prosecutor will be much more cautious than activists would like. It will in fact be even more difficult to demonstrate the individual responsibility of perpetrators of environmental crimes than of mass violations of humanitarian law, which is already a considerable challenge. Having said that, the will to extend the Court’s jurisdiction signifies a shift at a time when the ICC is being weakened by several African countries’ moves to withdraw their membership. The Court is trying to listen to the concerns of millions of people worried by natural resources running out, global warming, scarcity of drinking water and precious metals. All these things are worrying and we know they could lead to new conflicts.

In this sense, the Court’s interest in the crime of ecocide is symbolically important. It represents a realization at the highest level that the protection of human rights and protection of the planet are intimately linked.