Five years after January 14, 2011, many questions on what happened after the bloody nights of January 15, 16 and 17 have not been completely answered. Ben Ali, the fallen dictator, had nevertheless already left for Saudi Arabia. Here is a provisional account of a panic situation which includes the unexpected, common to revolutions.

Tunisian civil society, caught up in an overload of tense, fast-paced political events, perhaps forgot to demand the truth about various intrigues during the revolution that have been covered by a heavy official silence. The long trials of senior Interior Ministry security officials have done nothing to bring these truths to light.

Did the army fire on civilians?

Yes. This is borne out by statistics.

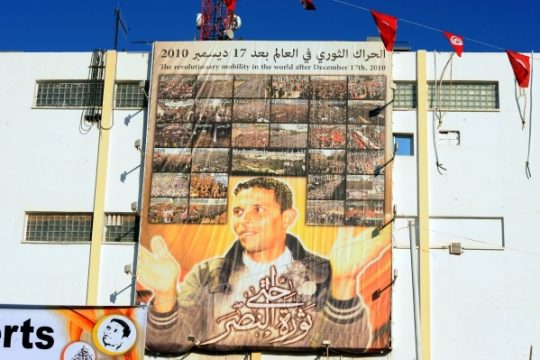

For their book entitled “The Investigation” (Apollonia Editions, April 2013), journalist Abdelaziz Belkhodja and Tarak Cheikh Rouhou, a young computer expert with a passion for information, followed a year’s work of the National Inquiry Commission on abuses recorded from December 17, 2010 to February 2011. Their research found that the army was tasked from January 7, 2011 to the imposition of a curfew five days later only with securing important national institutions. This mandate drew sympathy from the population, whose hatred of the police rose exponentially after the self-immolation of young street trader Mohamed Bouazizi on December 17, 2010.

The situation changed, however, after the ex-president fled to Saudi Arabia on January 14. After that, the army did not stay peaceful. On January 15, according to the book’s authors, 34 people were shot dead, of whom 20 by the army, eight by the police and six by unidentified gunmen. The next day, according to their investigation, 18 people were killed, of whom 10 by the army. On January 17, eight people were killed, of whom six by the army.

Soldiers fired during the ceasefire with a weapon of war, the Steyr assault rifle. “Even if the soldiers sometimes aimed at the legs, bullets from a Steyr can kill as they ricochet,” says Tarak Cheikh Rouhou. Some inexperienced officers, pupils of the Military Academy called as reinforcements during the state of emergency, fired hails of bullets, probably out of fear.

In journalist Pierre Puchot’s book “The Stolen Revolution” (Actes Sud, April 2012), there is this account from Hela Ammar, a lawyer and member of the Commission investigating the abuses: “It is clear that the soldiers, who were not much used to ensuring public order, committed many tragic mistakes during the period of the curfew. But nobody wanted to communicate about them for fear the population might push the country into chaos, say sources in the army and Interior Ministry.”

The myth of a Republican army during the revolution was a strong link with the population. To overturn it would shake the fragile balance in the turbulent times of “Tunisian explosion”, according to historian Kmar Bendana.

Were there any snipers?

That seems not to be the case. This semi-answer given by Beji Caid Essebssi, current President of Tunisia, when he was transitional Prime Minister in 2011, looks like an attempt to close the debate around grey areas of the revolution. His declaration met with scepticism at the time, notably in the media. Much had already been written about the professional sharpshooters, special units that do exist within the army, the Anti-Terrorist Brigade (BAT), the Presidential Guard and the National Guard.

The most fabulous tales circulated about these élite shooters, whose number is really quite small, saying they had been sent by the authorities to suppress the popular uprising. In Kasserine, witnesses claimed they had seen a female sniper as beautiful as a siren running across the town’s roofs. Others said they had heard snipers speaking Hebrew. One member of the Commission charged with investigating abuses, who interviewed hundreds of injured people, said there were not enough credible testimonies about this.

Paradoxically, it was the sniper psychosis mixed with a flagrant lack of coordination between the different security forces that killed more than the élite shooters themselves. Several pitched battles between soldiers and special units broke out on the roofs of Tunis buildings, with each thinking the other was part of these soldiers of terror.

Psychologist and senior police commissioner Yousri Daly was charged until January 14, 2011 with recruiting officers, agents and snipers of the Presidential Guard. He puts forward a hypothesis and makes a distinction between three periods. “On January 7 and 8, 2011, the security forces’ sharpshooters fired with 7.62 rifles, known to be used by snipers, from the roofs of their stations, either to terrorize the protesters or to defend their territory,” he says. “In Tala and Kasserine, they were confused with snipers. Around January 14, witnesses say they saw men in civilian clothes with sniper rifles. We think these people, ejected from the army or internal security forces for one reason or another, were militia put together in haste to help rescue the dying regime of Ben Ali. After January 14, I think there were lots of blunders committed by the army. For those who manipulated public opinion in the panic-stricken days after the ex-president’s flight, the snipers were a welcome diversion.”

Was the Presidential Guard plotting Ben Ali’s return?

No. As of January 14 evening, official communiqués from the Ministry of Defence accused the 2,500-strong Presidential Guard and its powerful director Ali Seriati, said to have fled to the south of the country, of trying to terrorize the population.

In fact Ali Seriati had been arrested on the orders of Defence Minister Ridha Grira at 18.17 on the evening of January 14 in the VIP room of the Aouina government airport. He had just accompanied Ben Ali and his family to their plane for Saudi Arabia and was calmly waiting for instructions from his boss, the ex-president’s daughter Ghazoua Ben Ali, and her husband Slim Zarrouk, whose departure to the island of Djerba he was supposed to oversee. Did he, in the chaos of the ensuing nights after Ben Ali left, try to make Tunisians regret their uprising against the regime and bring back their former Head of State as the saviour of their lost nation? Was he motivated by the lust for power of senior security officials?

Kmar Bendana tries to explain this situation where History seemed to have speeded up. “I think there were several people who wanted to lead a coup d’Etat, including people that Ben Ali had called to his aid in the run-up to January 14. The power vacuum might have lent itself to that,” she says. “There were conflicting interests, against a background of social crisis, but they finally wiped each other out.”

“It will take a lot of time to unravel the complexity of the event and establish a clear picture of what happened during those days of January 2011 when the chaos that is a feature of revolutions reigned,” she adds.

In principle, the Truth and Dignity Commission should in its final report establish the truth about these events and the chain of responsibility for orders to fire on peaceful protesters during that period. That could help shed light on a part of Tunisia’s history which is still obscure.