Let’s starts with the conclusions. On 21 January 2021, The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) established Russia’s “effective control” over the Georgian occupied regions and found Russia responsible for five major categories of violations: “killing of civilians, torching and looting of houses in Georgian villages and expulsion of Georgian civilian population”; “denial of Georgian nationals to return to their homes in Tskhinvali Region/South Ossetia and Abkhazia”; “unlawful and inhuman detention and treatment of Georgian civilians”; “torture of Georgian prisoners of war”; “failure to carry out an adequate and effective investigation into the killings committed during the active phase of hostilities and in the period of occupation.” The Court accepted Georgia’s argument that the violations form part of a repetitive pattern of acts and omissions that amount to an administrative practice incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

Georgia went to the ECtHR in the face of Russian military aggression with the aim of ending hostilities, human suffering and seeking redress for the victims. War was ongoing when on August 11, 2008, Georgia applied to the Court with a first request for interim measures. On February 6, 2009, Georgia filed a full application and invited the Court to find Russia in violation of eight articles of its Convention and Protocol, including “right to life”, “prohibition of torture, inhuman and degrading treatment”, “right to liberty and security”, “right to property,” “right to education” and “freedom of movement” and for its failure to carry out investigations into the incidents forming the basis of these violations.

In the same period of time, Georgia sued Russia at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and requested provisional measures against ongoing ethnic discrimination. The ICJ granted Georgia’s request on 15 October 2008, but declined to examine the case on merit, on a technical ground of non-exhaustion of negotiation obligation. In august 2008, as a state party to the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court (ICC), Georgia started to regularly communicate with the Office of the Prosecutor, while its own national criminal investigations were ongoing. In 2016, the ICC Prosecutor formally opened an investigation into potential war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Tskhinvali Region/South Ossetia. That investigation continues.

Duty to enable Georgians to return

Out if the three proceedings started by Georgia, the ECtHR judgment delivered last week is in fact the first comprehensive legal assessment of Russia’s accountability for gross human rights violations committed in the context of the August 2008 war. In Georgia, thousands of internally displaced persons and victims of the war are directly concerned by the judgment.

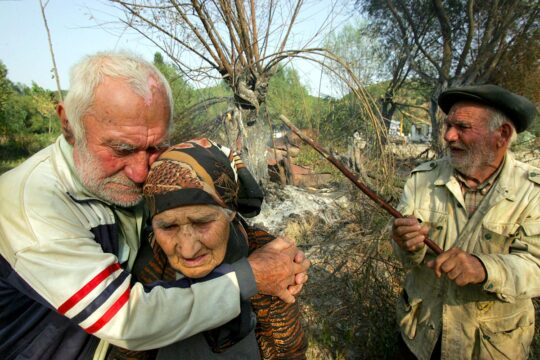

The Court accepted Georgia’s argument that the Russian Federation, through its regular army and de facto militias under its authority and control, engaged in a campaign of ethnic cleansing that had intensified after the cessation of the active hostilities on August 12 and lasted for months, ending only after nearly the entire ethnic Georgian population of Tskhinvali Region/South Ossetia had been expelled from their homes. Contrary to the Russian submissions that the de facto militias were responsible for these gross violations, the ECtHR considered that it had sufficient evidence to conclude beyond reasonable doubt that the crimes were perpetrated either with direct participation of Russian soldiers or with official tolerance from the Russian state authorities.

Although the ECtHR reserved the question of just satisfaction for victims for a later stage, the judgment unequivocally stated that the de facto South Ossetian and Abkhazian authorities, and the Russian Federation, which has today “effective control” over those regions, have a duty to enable inhabitants of Georgian origin to return to their respective homes. The judgment can therefore create optimism in Georgia about the outcome of a few hundred [about 270, editor’s note] individual applications related to unlawful killing, torture, destruction of property and denial of return, among other violations, pending at the European Court for more than a decade.

No “effective control” of Russia during the active phase of hostilities

One reasoning of the judgment, however, could raise legitimate concerns. The Court differentiated the complains on killings of civilians by bombings, shelling and artillery fire committed during the active phase of war (from 8 to 12 August), from the systemic campaign of killings of civilians in the period of occupation after the cessation of hostilities on August 12. While the ECtHR found Russian Federation responsible for the killing of civilians (along with looting and destruction of property) in the later period of its military occupation, it refused to enter into the examination of killings committed during the first period, in the course of active hostilities (bombing, shelling, artillery fire) aimed at obtaining territorial gain or advancement. The Court considered that, due to “the very reality of armed confrontation and fighting between enemy military forces seeking to establish control over an area in a context of chaos” Russia had “no effective control”, nor jurisdiction, during the first period.

we find it troubling that the Court remains reluctant to hold a state responsible for its violations of the Convention perpetrated extraterritorially in international armed conflicts and treats it as an almost exclusive matter of international humanitarian law."

The Court also stated that a State’s responsibility could not be engaged in respect of “an instantaneous extraterritorial act”, as the Convention does not recognize a ‘cause and effect’ notion of jurisdiction.” In the words of the ECtHR, “such situations [conduct of hostilities in international armed conflict] are predominantly regulated by legal norms other than those of the Convention (specifically, international humanitarian law or the law of armed conflict),” as it involves “large number of victims and contested incidents, the magnitude of the evidence produced,” and it is associated with “the difficulty in establishing the relevant circumstances.” The ECtHR admitted that this approach “may seem unsatisfactory to the alleged victims of acts and omissions by a respondent state during the active phase of hostilities in the context of an international armed conflict […], as well as to the state in whose territory the active hostilities take place.” Indeed, we find it troubling that the Court remains reluctant to hold a state responsible for its violations of the Convention perpetrated extraterritorially in international armed conflicts and treats it as an almost exclusive matter of international humanitarian law. Paradoxically, the same actions committed on the state’s own territory, in the context of non-international armed conflict, would trigger application of the Convention.

At the same time and equally paradoxically, the ECtHR did not hesitate to find Russia responsible for its failure to investigate all allegations of unlawful killings, whether they were committed in or after the active phase of hostilities. In the face of seriousness and the scale of the crimes committed, the investigations carried out by the Russian authorities were considered “neither prompt, nor effective or independent” by the judgment.

Justice for victims will not be served easily

Justice for Georgian victims will not be served immediately or easily. The ECtHR will have to further elaborate on Russia’s obligations and determine the most appropriate measures for victims in the individual applications pending before the Court, potentially within one or two years. Effective investigation and compensation will be considered for individual victims, along with the duty to ensure return of internally displaced Georgian population. On its own side, the government of Georgia will have to continue engagement with the Court to make a comprehensive claim on just satisfaction.

Both judgments, on the interstate and on individual cases, will be sent for enforcement to the Committee of Ministers, the Council of Europe’s political body. Contrary to its international legal obligations, Russian Federation refuses to comply with decisions of international courts, including the ECtHR, if it determines that the enforcement would violate its Constitution. Russia has not yet enforced a first judgement delivered on January 31st, 2019. In this case, the Court awarded 10 million euros to at least 1500 Georgian nationals arrested, mistreated and expelled from the Russian federation in 2006, in response to an arrest of Russian spies in Tbilisi, capital of Georgia.

The significance of the Georgia v. Russian Federation second interstate judgement delivered last week in Strasbourg goes beyond the cases originated from the Russia-Georgia war of 2008 and will certainly have impact on the pending interstate and individual cases related to war-time application of the European Convention, including the one filed by Ukraine re Crimea. Victims of human rights violations committed in armed conflicts continue to benefit from the Convention protection and the Court can and must be a guarantor when domestic legal remedies are not available.

Tina Burjaliani is a Georgian lawyer who served as the First Deputy Minister of Justice (2007-2012) responsible for international litigation. Earlier Ms. Burjaliani was head of Legal Department at the Office of Prosecutor General and Government Agent to the European Court of Human Rights. She also worked as Senior Advisor at the American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative’s Middle East and North Africa Division.