JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

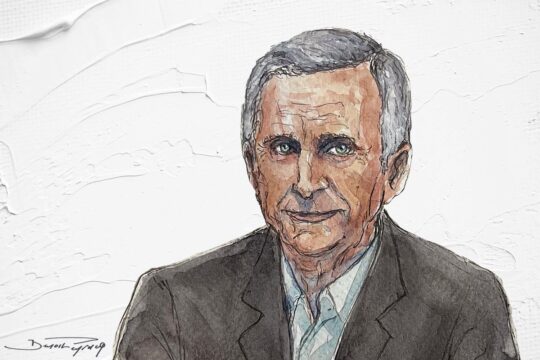

Leigh Payne

Latin America has been a hotbed of attempts to hold business accountable for serious human rights violations. Oxford sociology professor Leigh Payne has been working on the topic for decades. She explains how this region of the world has been able to multiply strategies and achieve some success.

JUSTICE INFO: How does your perspective as a sociologist rather than a lawyer allow you to approach the subject of corporate responsibility in serious crimes in a different way?

LEIGH PAYNE: As a sociologist, I find the focus on law frustrating because if you look at the world in terms of “law on the books”, it seems like a really wonderful place to be. But the gap between what we call “law on the books” and “law in practice” is enormous. There's a big gap between what is right, how to protect victims, and how victims can access those rights on the books in everyday practice.

In the field of corporate accountability you can see lots of ways in which the law could be interpreted as business having specific obligations, responsibilities, duties and obligations. And yet, there is an argument made in the legal scholarship that, in fact, there are no binding or enforceable obligations on business. How is this possible? How can victims have the right to truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-repetition on the books, but lack the binding or enforceable mechanisms to realize those rights? How can those legal instruments become applicable? What innovative lawyers have been able to do is to find creative ways around legal constraints and advance initiatives for victims of corporate abuses to realize their rights.

What we are trying to do as non-lawyers is to think about what is possible, what can become possible, and how we make it possible by looking at the key actors in society who are doing the work. The matter is: how are the victims able to gain access to truth, justice, reparations and the guarantees of non-recurrence? There is a real struggle. We've tried to identify what factors seem to be at play in making it possible for victims, who are weak actors in the Global South, to still stand up to these powerful domestic companies, sometimes multinational, who have all the protections of top lawyers.

Almost every country in Latin America has incorporated international human rights law into domestic law. It means victims don't have to depend on international courts but they can depend on local courts to apply the law.

On some level you could say: we don't really need transitional justice because a lot of instruments are already in place for victims in ordinary laws. Transitional justice has identified patterns of abuses that occurred within and across countries experiencing authoritarian rule and armed conflict. Once those patterns were identified and connected to existing international human rights laws, then victims and human rights advocates could mobilize to incorporate those international human rights laws into domestic constitutions.

Almost every country in Latin America has incorporated international human rights law into domestic law in the form of constitutions, but also in criminal law codes. It means victims don't have to depend on international courts but they can depend on local courts to apply the law, and it's the law of the land. Transitional justice, therefore, is not necessarily a special form of justice, but the application of justice to address human rights wrongs during authoritarian or armed conflict pasts.

In Latin America, and elsewhere, international human rights law is not required in law faculties. It thus becomes very important to have these laws incorporated into domestic law and to be able to rely on those laws. Judges understand that they need to apply domestic laws – laws incorporated into constitutions and criminal and civil codes. They may not understand that they can apply international laws.

A functioning watchdog or monitoring body exists in Latin America that has not yet evolved in other regions of the world.

Why is this region an example in having corporations challenged in courts?

We found that in African or Asian countries, victims have had to use foreign courts, like in the Netherlands or in France, to adjudicate these cases. One reason is that the domestic human rights law instrument and the set of human rights law innovators are not as strong outside Latin America. A powerful regional human rights body, moreover, exists in the region: the Inter-American Commission and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. That system has ruled against member states in Latin America for failing to adopt into their own legislation the region’s human rights. Indeed, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights can rule against member states that have violated the Inter-American Convention. This acts as a pressure on states to adopt those Conventions that are meant to be binding on member states. In short, a functioning watchdog or monitoring body exists in Latin America that has not yet evolved in other regions of the world.

There is a mobilized, organized civil society that's making demands for its rights in every Latin American country.

You wrote in one of your articles that “the transitional justice efforts in several Latin American countries could become a global model for promoting the accountability of economic actors for their involvement in serious human rights violations”. What’s specific about transitional justice in Latin America?

We have, in Latin America more than any other region in the world, a concentration of human rights trials and truth commissions. First, as I said, because we have the Inter-American Commission and Court of Human Rights. Every year, it goes to another part of Latin America. It has hearings where justice scholars and practitioners can participate, for example in Bogota, or more recently in Washington D.C. So there is an engagement with civil society by the Inter-American Commission and Court. It doesn't just write reports, it also brings countries to court if they violate human rights provisions embodied in the System’s Conventions.

The other reason is that the legal community in Latin America has been very strongly supported by international groups. The most powerful human rights NGOs in the world are in Latin America: CELS [Center for Legal and Social Studies] in Argentina, Dejusticia in Colombia, different NGOs in Mexico, etc. There is a mobilized, organized civil society that's making demands for its rights in every Latin American country. I don't want to give the impression that Latin America is uniform in this; there's a lot of variation between Brazil and Argentina, for example. But comparing to other regions in the world, there are more countries with internationally supported human rights organizations that have been able to do some of this creative thinking.

There are also legal practitioners who come out of an experience of gross violations of human rights and have committed their lives and their careers to promoting human rights. Many of them were trained outside Latin America; they were exiled during the dictatorship, so they began to have their formal training outside the region during a period of time in which authoritarian systems dominated in the region. When they came back to their countries, they worked hard, particularly with the Inter-American Commission, to make sure that there were advances in these areas of rights. They are very powerful protagonists. But they come up against very powerful “veto players”, as we call them, because we have a strong conservative legal tradition in Latin America. In this David and Goliath story, you sometimes have victories for the weaker civil society forces in the region, even where you might not expect them.

Some of these veto players involve companies that were domestic companies and grew into Latin American multinationals or “multilatinas”, as they're called. They are companies doing business all over the world that have grown very powerful and capable of resisting those kinds of demands for human rights protections for victims of corporate abuse.

Step by step we brought together people who have been at the forefront of advancing corporate accountability. We created a network and we also have been preparing a set of guidelines for how to advance these cases.

How was your approach to transitional justice built on the issue of corporate responsibility and for what purpose?

I began to work in the area of transitional justice before we had a name for it in the 1980s. I was working on my doctoral thesis on Brazilian business elites who had participated in the 1964 coup and how they responded to the transition to democracy. Some of them were beginning to speak about the "truth about the authoritarian regime". Later, when I began working in the defined field of transitional justice, I was not looking at business, but rather how to determine whether truth commissions, trials, and amnesty laws contributed to strengthening democracy and lowering human rights violations. A subsequent project examined “alternative accountabilities” and we considered mechanisms to hold non-state actors responsible for human rights violations; I began looking again at business during dictatorships and armed conflicts. Then, around 2011, I had lunch in Oxford with a member of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights who knew that I was working on transitional justice. She asked me if I might be interested in building a database to see if the Ruggie principles work. [The UN’s Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, known as the Ruggie Principles, formalize the concept of "due diligence" and its application to companies through proportionate measures to identify, prevent and remedy the negative impacts of their actions on human rights.] I answered that I would be very interested in building a database to evaluate whether the role of transitional justice in holding businesses accountable for past human rights violations, but I could not determine if the Ruggie Principles were relevant to that process.

Gabriel Pereira, now a law professor at the University of Tucuman [north of Argentina] and a founder of a human rights NGO called Andhes, joined me. Andhes brought some initial cases for violations by companies in the north of Argentina, mainly sugar mill companies. They were famous cases of torture, killings, and disappearance of workers and others by these powerful companies in the region. Next Laura Bernal, a sociologist and law professor at the Javeriana University in Bogota who had written her thesis on the successful trial against palm oil companies by Afro-Colombian victims of human rights abuses. She joined us and the three of us built the Corporate Accountability and Transitional Justice database.

Step by step we brought together people who have been at the forefront of advancing corporate accountability and we are now working with prosecutors, judges, and advocates to think about what lessons we can take across borders to remove blockages to accountability. We created a network and we also have been preparing a set of guidelines for how to advance these cases.

For example, during the Argentine dictatorship and elsewhere, there were cases of workers who were disappeared from the workplace. They went to work that morning and were never seen again. The companies where they worked were implicated in the disappearance. In some cases, the companies had their own detention centres on site. Creative efforts have been used to try to hold companies accountable for these disappearances. These creative efforts involved a blending of labor laws and international human rights norms embedded in domestic constitutions. Labor law in Argentina requires companies to protect the safety of workers. Their disappearance from the workplace violates those protections. However, those safety protections have a statute of limitations of only a couple of years; the statute of limitations had run out by the time it was possible to bring these cases after the end of the dictatorship.

Under international human rights law, that is also incorporated into Argentina's constitution, there is no statute of limitations for crimes against humanity. Disappearance is a crime against humanity. Therefore, innovative strategies were adopted to hold businesses accountable for their failure to protect workers' safety from disappearance, blending domestic labor law and international human rights protections in the country's constitution.

The aim of our corporate accountability collaboration is to put more tools in their hands of victims and their advocates, to better defend victims of corporate human rights violations. By developing a network of support if something does happen – if somebody is threatened, if somebody is intimidated – we can alert people and raise visibility to these tactics to suppress accountability.

In Brazil, a group of businessmen organized a way to help finance the dictatorship’s repressive apparatus to end conflicts with labor. Some companies even had their own detention centers on the company premises where employees faced tortured.

Did you identify specific stories of violations and reparations?

We did a study of all the published truth commissions reports that we could find. And we went through and looked for any reference to companies in relation to violations of human rights. In Guatemala, there are a few big companies like Coca Cola that were mentioned in the report. In addition, a number of powerful landholders in specific regions were mentioned who lack the kind of global power of Coca Cola. In Brazil, with the huge incentives for foreign investment before and during the dictatorship, multinational investment by firms such as Volkswagen, Mercedes, Ford and Fiat occured, but national companies like Petrobras or Odebrecht also grew during the dictatorship. The coup was in 1964 and these companies remain powerful today. Many were involved in supporting the coup, the dictatorship, and its repressive apparatus.

To give a more concrete model, Volkswagen was operating in the industrial area around Sao Paulo during the dictatorship. At the same time, trade unionists were developing. A group of businessmen organized a way to help finance the dictatorship’s repressive apparatus to end conflicts with labor. Some companies even had their own detention centers on the company premises where employees faced tortured. The National Truth Commission didn't pay attention to these violations initially. It didn't have a mandate to investigate corporations’ involvement in human rights violations. It was the Sao Paulo Truth Commission [set up in 2012 in parallel to the National Truth Commission] that really focused on the business and its role during the dictatorship. The trade union movement had worked with that Commission to carry out investigations; they produced documents sent to the Sao Paulo Truth Commission who conducted research in the archives of the business federations in Sao Paulo. Local Commission actors and trade unionists then pressured the National Truth Commission. The national Commission eventually included the Sao Paulo findings in the final report. The recommendations of that report were to investigate criminal violations of human rights. Sao Paulo state prosecutors began these investigations against Volkswagen drawing on trade union’s research and documents. Eventually, with strong pressures from Brazil and Germany, Volkswagen agreed to settle the case with individual and collective reparations. They also agreed to build a memory site in Brazil and to support investigation into other companies activities during the dictatorship.

We have violations in the mining sector in Peru, in sugar mills in Argentina, auto manufacturers in Brazil, and landholders in Guatemala. It really is quite a range of companies.

Did you identify what types of businesses have been prosecuted in Latin America? Were they only large companies or also small companies and in which particular sectors?

We thought there would be a targeting of the mining sector because of so many violations. But in fact, we find everything, including small businesses. We have violations in the mining sector in Peru, in sugar mills in Argentina, auto manufacturers in Brazil, and landholders in Guatemala. It really is quite a range of companies.

In the case of Paine, in Central Chile, the individual who was prosecuted, Juan Francisco Luzoro Montenegro, owned a transportation company but he was also a landowner. The people of Paine had received land under the Frei and Allende governments before the Pinochet dictatorship. They were political activists; some of them were part of the armed left. During the dictatorship, a high number of community activists were tortured and massacred. Some of the bodies have never been found. The military police was found guilty in that case but also Luzoro was held accountable in the Chilean high court.

One of the big successful cases is the Argentine case against Ford Motor Company. Two top officials in the Ford Motor Company were found guilty and were sent to prison for similar kind of story as Volkswagen: torture within the Ford plant in Argentina. That case was also brought simultaneously in US courts, but has not advanced. These executives have appealed the Argentine decision. The employers are 92 and 95 years old, however, so it is likely they will die of natural causes before the appeal is completed. But they may die convicted for the role they played in the torture of the 1970’s.

Since that Shell agreement, the US Supreme Court has made it harder and harder to bring cases through the Alien Tort Statute.

The dictatorship period in Latin America is 40 or 50 years ago. What about current violations?

I just came back from Colombia where, despite the peace accords, a conflict continues. Violations today are definitely linked to the transition and transitional justice process. People who work in business and human rights still hold out hope that the courts in the “Global north” might prove powerful enough to get convictions for ongoing – post-transition -- human rights violations around the world. The United Kingdom, France, Switzerland are beginning to consider adopting national laws that allow their courts to hold companies accountable for crimes against humanity that are committed outside their countries and by non-national companies.

This was what has been tried in the US under the Alien Tort Claims Act. It's a civil claim so you can't put individuals in jail but you can fine them heavily for the harm that's committed. Crimes against humanity, genocide are against the law of nations. So that would enable US courts under this statute to hear those cases even if the crime did not take place on US soil or did not even involve a US company. That's what happened with Shell in Nigeria: it was brought to courts in the US for civil claims. Shell is a Dutch company, the crimes were committed in Nigeria, but the US courts nonetheless took the case. Eventually Shell settled a very dramatic settlement for the Ogoni people in Nigeria who were victims of massacres. It was a success. But since that Shell agreement, the US Supreme Court has made it harder and harder to bring cases through the Alien Tort Statute.

Why?

In recent decisions the US Supreme Court has limited the possibility of taking these cases through the US courts because there's not enough, as the Supreme Court justices said, “touch and concern”. It doesn't touch our land and it doesn't concern our people enough, they said. Another decision that weakens the use of this Act for corporate accountability relates to foreign policy: that when there are foreign policy considerations, US courts should not be involved since they are not foreign policy making bodies. The new developments in Europe have a lot of potential to fill a gap left by the Alien Torts Statute. But this is at a preliminary stage without any certainty about whether the same kind of pushback that has happened in the US will also happen in Europe.

The transitional justice in Colombia really tried to make up for all of the past gaps in accountability. Now, because of political pressure, it may end up being a very limited process.

If you take Colombia and its comprehensive transitional justice process, how do you see it addressing corporate accountability for serious crimes?

In our conversations with some of the attorneys in Bogota, they prefer to resort to ordinary justice because transitional justice has become too politicized. There's so much pressure against it from the government [This interview took place before the change of government in Colombia following June’s presidential and general elections] that everyone who's trying in these leadership positions is being threatened. In a country of 50 years of violence you really don't ignore those security threats.

So that's a little bit disillusioning because the transitional justice in Colombia really tried to make up for all of the past gaps in accountability. Now, because of political pressure, it may end up being a very limited process. On the other hand, cases are going through the ordinary courts. We had some astonishing victories like for the Afro-Colombian workers on palm oil plants who have seen justice in ordinary courts against palm oil companies, or the Chiquita Brands case and the Drummond case.

In fact, what I take away from the project on corporate accountability as a lesson is this: Try wherever you can. Go international. Go foreign. Go transitional justice. Go ordinary courts. Be creative. Do everything you can because these cases are really hard to win.

Interviewed by Clémentine Méténier

Leigh Payne is a professor of Sociology and Latin America at the University of Oxford, St Antony’s College, UK. She is the author of numerous books and articles on transitional justice in Latin America, including Disappearances in the Post-Transition Era in Latin America, edited by Karina Ansolabehere, Barbara Frey, and Leigh Payne, Oxford University Press (2021) and Transitional Justice and Corporate Accountability, edited by Leigh Payne, Gabriel Pereira and Laura Bernal-Bermúdez, Cambridge University Press (2020).