On 15 December 2025, an assize court in Paris found Congolese former rebel Roger Lumbala guilty of complicity in crimes against humanity committed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) between 2002 and 2003. He was sentenced to 30 years’ prison. The case has been covered extensively by Justice Info.

Lumbala’s conviction has been celebrated by victims’ rights organizations. According to the Baltasar Garzón International Foundation, which advocates universal jurisdiction trials, it has been a “landmark ruling [that] marks a significant milestone in the fight against impunity for crimes committed during the Second Congo War.” The charges addressed Operation “Effacer le tableau” (Wipe the Slate Clean), a military campaign that terrorised eastern Congo in 2002 and 2003. International organizations and civil society groups have recorded atrocity crimes in the DRC for decades. This work is reflected in the 2010 UN Mapping report, a seminal document which detailed the violence in the country between 1993 and 2003. Regardless, Lumbala is arguably only the third person, after Germain Katanga and Bosco Ntaganda, to be held responsible either internally or internationally for the extensive, devastating violence directed against civilians in DRC.

Although the verdict represents accountability after decades of impunity, the case also exposes the downsides of universal jurisdiction practices. These shortcomings are both principled, in terms of the purpose of criminal punishment, and procedural, in terms of how accountability is balanced against the defendants’ rights.

Procedural Risks: Ensuring the Rights of the Defence

Public trials serve several social roles. As exercises in rule of law transparency, they communicate what sort of behaviour is criminal while simultaneously ensuring the defendant’s rights. Defendant’s rights begin with the presumption of innocence, which requires the prosecution to prove guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt” (common law) or “intime conviction” (French law). Defendants also enjoy the right to a fair trial which includes legal representation.

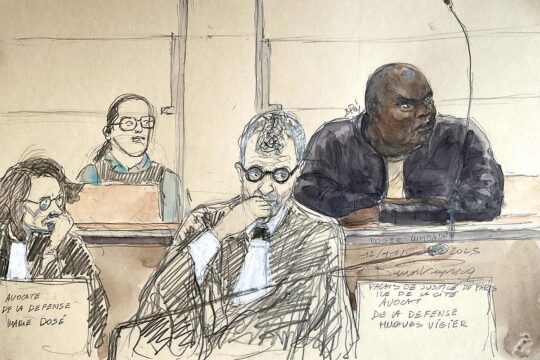

At the start of trial, Lumbala and his attorneys vigorously contested the right of the Paris court to hear the case, raising arguments that had been heard, and rejected, prior to trial. At the end of the first day of trial, having failed to obtain with these arguments, Lumbala “fired” his attorneys, announced that he did not recognise the court’s jurisdiction, and refused to participate in the trial.

Faced with an absent defence, the judge ordered Lumbala’s attorneys to serve the court as “commis d’office” appointed by the court to serve the interests of the defence. Lumbala’s attorneys refused the court’s request, arguing that it would breach their professional responsibilities to act so blatantly in opposition to their client. For the remainder of the trial, the defence bench sat empty, with neither Lumbala nor his attorneys in attendance.

We have seen “commis d’office” counsels in relation to atrocity crimes before, most notably in the work of the Chambres africaines extraordinaires, the special court established in Senegal that tried, and convicted, Chad’s ex-president Hisséne Habré in 2016. In that case, attorneys appointed by Habré also utilized what is termed “defense de rupture,” challenging the process of the trial itself by refusing to participate. At the opening of the Habré trial, therefore, the court adjourned for 45 days while it appointed defence counsels to represent Habré’s interests, against his will. Habré did not cooperate with or recognize these attorneys. Nonetheless, they represented his “interests” before the court by raising legal challenges in his name. These challenges included procedural challenges, i.e. ways in which the Habré court’s actions violated the procedural rules under which it was constituted, as well as content challenges, for example to proof and witness statements.

The Paris court asked Lumbala’s appointed attorneys to both represent the interest of the court and the interest of the defendant and they refused. Instead of adjourning the proceedings to appoint other counsels, incurring further delays in an already years’ long process and sacrificing the resources already employed in constituting the jury, scheduling the witnesses, and reserving the court’s time, the Paris court continued the trial, concluding on schedule with a conviction.

Trials in absentia are permissible in France. Moreover, the system is designed to represent the defendant’s interests throughout the whole judicial process, meaning that the dossier that makes it to trial includes the defendant’s arguments. Nonetheless, the absence of a participating defence clearly stymied the judge president, who paused the proceedings several times, asked the victims lawyers and the prosecutors for their observations, and muttered various versions of “this is nuts!” in the days that followed.

Principled Risks: The Purpose of Criminal Prosecution and Punishment

Criminal punishment serves both an individual, anti-recidivist agenda as well as a collective, communicative agenda. Criminal law professionalizes vengeance, moving private conflicts into the sphere of the state. By routinizing and standardizing punishment, criminal law transforms individual convictions into broader social messaging regarding what sorts of behaviour is permissible, seeking to deter impermissible behaviour.

International criminal law justifies individual trials in similar terms, even though many of the rationales legitimizing criminal law as social control are absent. Universal jurisdiction, wherein international atrocity crimes are tried in third countries, cannot address these absent justifications. A central communicative element of domestic criminal law is predictability, establishing what behaviour is impermissible and subject to punishment. Universal jurisdiction does not predictably address criminality through punishment, however. This is because it is by necessity opportunist, trying only tiny subset of atrocity cases based on a series of contingent, chance-based factors, such as foreign perpetrators having their names flagged in an administrative process, as happened with Lumbala.

Research on universal jurisdiction prosecutions suggests that there is bias in those prosecutions, where low level perpetrators are significantly more likely than high level perpetrators to be brought to justice. This represents another aspect of universal jurisdiction as a challenge to rule of law principles, since law’s legitimacy depends on its application regardless of social position. The Lumbala case can also be seen in this light. On the one hand, Lumbala is a former leader, and therefore an outlier in data showing that universal jurisdiction cases skew towards low-level perpetrators. On the other hand, Lumbala found himself before a French court after falling out with leadership in DRC, having become so politically weak and threatened that he was seeking asylum protection in France. The International Criminal Court has been critiqued in this same vein, as “a court that only tries rebels.” Principled rule of law applications also suffers when defendants must be weak before the law can touch them.

Finally, universal jurisdiction removes atrocity crimes from the communities, circumstances and contexts in which they occurred, challenging their communicative potential. When quitting the trial, Lumbala told the court:“This is reminiscent of past centuries. The jury is French; the prosecutor is French. This court does not even know geographically where DRC is!”

According to information France provided the UN Secretary-General, Lumbala’s conviction is the ninth conviction obtained under universal jurisdiction since France changed its law to allow it. According to this same report, several other investigations leading to possible trials are ongoing. A central question remains unanswered: what message will these trials send, and to whom?

Kerstin Carlson is an Associate Professor at Roskilde University (Denmark), where her work focuses on the development of international law and legal institutions in the practice of transitional justice. She also teaches at The American University of Paris, where she is co-director of the Justice Lab. She is the author of The Justice Laboratory: International Law in Africa (Chatham House/Brookings Institute, 2022) and Model(ing) Justice: Perfecting the Promise of International Criminal Law (Cambridge University Press 2018).