Four white plaster walls and a reddish brown metal roof. All houses are identical, in Shavshvebi, central Georgia. The sleet, Covid-19 and lack of activity during this holiday season do not encourage anyone to go outside. The alleys of the housing estate are on a perfect grid; you only need to know how to count to get to the house of Natela Kebersaeva, an Ossetian married to Levan, a Georgian. The couple fled with their children when the first bombs began to fall on Kermeti, their village in South Ossetia, on August 7, 2008.

Twelve years later they are still here, in this camp for "internally displaced persons" on the highway leading to Gori, hometown of Joseph Stalin, who was Georgian. Natela has created a sewing workshop, a kindergarten and a small association called Hope for the Future, which works with other larger NGOs based in the capital, Tbilisi. Before the holidays, Natela received a message from Eka, the coordinator of the local office of the International Criminal Court (ICC), informing her that the Trust Fund for Victims was opening an assistance programme. A call for projects will be launched in March, the message said. Will she respond? "We are a group, we will decide together," Natela answers. “I have a small project that I have called 'Dignified Old Age'," she continues. “I have just three beneficiaries, whom I help with medication. But I know at least 30 people who can't afford medication or who are in need of psychological care. "Each displaced person receives only 45 laris per month (about 11 euros) in state aid, “she says. "Without solidarity, it is impossible to survive.”

30,000 internally displaced

Less than 50 kilometres away lies Tskhinvali, capital of South Ossetia, a territory that was taken from Georgia in the 2008 war. It is a destination now out of reach for all those who, like the 177 families of Shavshvebi, fled this separatist republic of some 50,000 inhabitants - including 10,000 Russian soldiers. Those who live there have only one way out, to the north, through the Roki tunnel and the Russian Federation. Higher up, at 5,000 metres above sea level, Mount Kazbek dominates this imposing natural border that divides the South from the North Caucasus. At its foot is a Russian military fortress, which can be identified by its high telecommunications tower. It guards the winding kilometres of barbed wire that the Georgians call "the line of occupation" and the Russians call "the border of the State of South Ossetia". In 2008, Georgia had to find urgent long-term housing for nearly 30,000 people. They came on top of 212,000 displaced persons mostly from Abkhazia and South Ossetia who had already fled the post-independence conflicts in the early 1990s.

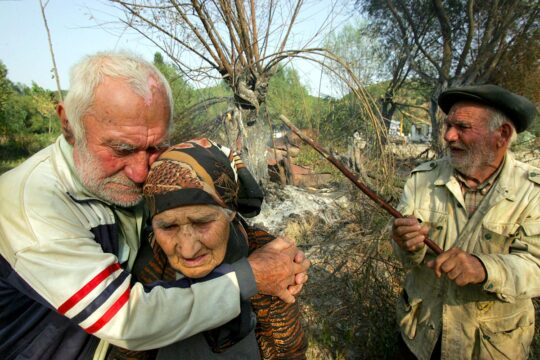

When she fled under the bombs through the forest, Natela could not take her bedridden mother, who remained in their large house surrounded by the orchard that made a relatively good income for them. Of Ossetian ethnicity, the old lady was not a target for the Ossetian militias, supported by the Russian army, who were striving to drive out the Georgians. “The fighting lasted five days," Natela recounts, "from August 8 to 12, resulting in 850 civilian and military deaths. A month later, the Russians were still in Gori; it was the status quo. “I decided to fetch my mother, with the help of my brother who lives in Vladikavkaz [North Ossetia, part of the Russian Federation]." Natela went through the checkpoints, mingling with a group of Azeri women who had come to sell aromatic herbs. "Everything was frightening, the cars without plates, the men in arms drunk and badly shaven. I found my brother and we arrived in the village. Not a single house was standing, all were burned, looted. My mother had disappeared. Our cows were wandering in the garden, a diploma and pictures were soaking in mud, with forks and bits of broken plates.”

"We've lost everything"

Natela went to the Red Cross in Tskhinvali and declared her mother's disappearance. She went through the checkpoints again, in the other direction. Later, her brother who stayed in Ossetia had news of their mother. "Some Ossetians found her lying in the garden in shock, and it took her three months to remember her name,” says Natela. “My brother took care of her in Vladikavkaz for the next six years. I was not able to see her again or bury her. We lost everything, what we had, our loved ones, our relationships.”

Natela looks around the living room with its fluffy carpeting. "We got zhis house on December 3, 2008," she says. It has 63 m2 of living space, a small plot of land and a garden, where her husband has planted a vineyard, allowing her to honour a tradition and offer guests a taste of their wine. We toast to the future. Can the ICC contribute to it? “I don't know who should be punished," says Natela. “I only know that Russia has occupied 20% of Georgia's territory and should pay for it. The government has a long list of lost properties." Georgia, a state party to the ICC, contacted it in the early hours of the war. After eight years of preliminary examination, it opened an investigation in 2016. Four years later, in Shavshvebi, no one seems to be waiting any more for its conclusions. No one believes Russians will be put on trial at the ICC.

A hundred kilometres to the east is the border with Azerbaijan. Here, 123 families from South Ossetia have been relocated to a building with peeling paint. The city is called Gardabani and is especially famous in Tbilisi for its thermal power plant, "Block No. 9", which has regularly plunged the capital into darkness. "We have heard about the ICC, of course!" laughs 73-year-old Tina Nebieridze. This displaced person from Ossetia recounts and mimes with gestures her escape from the village of Kekhi, her detention in a Tskhinvali prison that its occupants called a concentration camp ("it was a cage; from above, they threw dry bread and razor blades at us so that we would commit suicide"), her exchange eleven days later for Ossetian prisoners of war taken by the Georgian army ("I wanted to strangle them, they were so clean"). “I no longer have any hope in justice," she says. “For twelve years they've been laughing at us, the government as well as the others in Strasbourg or The Hague. I'm sick and have to take medicine. My neighbours help me with theshopping, but I have no one, and there's only one thing left to do: give my apartment to someone who, in exchange, will bury me." Her brave anger makes her neighbours laugh. She slips an apple and a cake into our pockets and limps along with us to the elevator. "The government has just installed it. It's broken down.”

ICC victims’ assistance

"I don't think the ICC investigation will be successful,” says Nika Jeiranashvili of the International Justice organization, back in Tbilisi. “For Georgia, it's over, the only thing that can make sense is the victim assistance mandate." This elegant man with his colourful ties and neat moustache, has dedicated most of his life in recent years to this issue, moving to The Hague. “There are five or six organizations working on it," he explains. “We work with victims, we provide medical care, psychological rehabilitation, legal services and representation in court in Strasbourg and The Hague. We try to defend the victims but nobody cares, they are no longer on the agenda.”

Other Georgian activists are also disappointed. "When we started to work actively with the ICC, our hope vanished,” says Nino Jomarjidze of the Georgian Young Lawyers Association, Gyla, which represents 300 of the 5,782 Georgian victims officially "participating" in ICC proceedings. “Every response from them was like 'it's confidential' or 'we can do it without you'. It took us five years, but the trust of victims and civil society disappeared."

Nino Tsagareshvili, of the Human Rights Center HRIDC, criticizes what he calls a "non victim-oriented approach". "The decision of the ICC to receive victims' applications does not give rise to formal rights, there is no procedure for submitting information or evidence. It is a problem not to be able to engage with the Court.”

Survey of 2,400 families

From then on, as if waiting for Godot, Georgian civil society began to lobby for an intervention by the Trust Fund for Victims. It had never happened before the ICC opened a case, but they succeeded. This lobbying was based on an extensive study of the displaced, ten years after the war. “In 2018, we went to meet the victims," Tsagareshvili recounts. “ It was six months of work during which we interviewed 2,400 families in 36 sites for the displaced on their living conditions, their needs and their expectations." The report points out the shortcomings of the ICC. It says that due to a lack of outreach and public information, only "49% of victims said they had heard about the ICC, and they had little information about the work, mandate and role of the Court. »

But above all, the study provides a wealth of information and recommendations, transmitted to the ICC and the Trust Fund for Victims, on the conditions of housing, transport, communication, access to education, employment, and health of the displaced in 2008. "It was about saving time," says Jeiranashvili, and Jomarjidze adds that "we gave them a lot of information". Nevertheless, the Fund hired a consultant, Ucha Nanuashvili, a former Ombudsman from Georgia, to conduct an assessment. “It's essentially a cut and paste of the civil society work,” complains an activist. The document is not public, but a summary is due to be published in February by the Fund, Nanuashvili says. Asked about its recommendations, he says: "There is a need for material support, livelihood assistance, and income-generating programmes, because unemployment is a serious problem among the victims. In addition, psychological rehabilitation and medical care are also areas where victims need some assistance.”

Call for proposals

Another two years passed. On November 10, 2020, the Fund's Board of Directors decided to allocate 600,000 euros for a three-year assistance programme. This decision was announced in a press release and in a video, recorded in Georgian by a member of the Fund's Board of Directors, Gotcha Lordkipanidze. Currently Justice Minister of Georgia, he is also one of the six new judges recently elected by the Assembly of States Parties to the ICC. In the coming weeks, the Fund is expected to publish a call for proposals. And a new waiting period will begin after the submission of applications. "In the best case scenario, victim assistance will not begin until next year," says Jeiranashvili. "Rehabilitation alone would be stupid,” he says. “The main problem is to find a job for the displaced people. Many of them are farmers, wine-growers, they know how to make clothes, and have professional skills.”

Mariam Jishkariani heads an NGO founded in 1996, RCT Empathy, which specializes in the psychosocial treatment of trauma related to torture and war. She is in contact with the Victims Participation and Reparations Section and the ICC Prosecutor's Office regarding the cases of 140 war-affected people. For Jishkariani, the arrival of the Fund is an opportunity for her to respond, in a "holistic" way to the demands of ICC investigators, which require months of unpaid work. Lawyers also work pro bono when it comes to the ICC.

"Ethnic cleansing must be recognized"

Some of the victims are elderly, some have died of old age, the stress of war, brutal social changes, chronic diseases," says Jishkariani. “They need medical and psychological care, but also effective legal remedies. Their rehabilitation will be incomplete without it. They were in the midst of ethnic cleansing, and this needs to be recognized." And according to Tsagareshvili, “the Fund represents a chance to do something for the victims, who are simply losing hope because they don't see any perpetrators arrested, or reparations provided".

Meanwhile, the waiting continues.