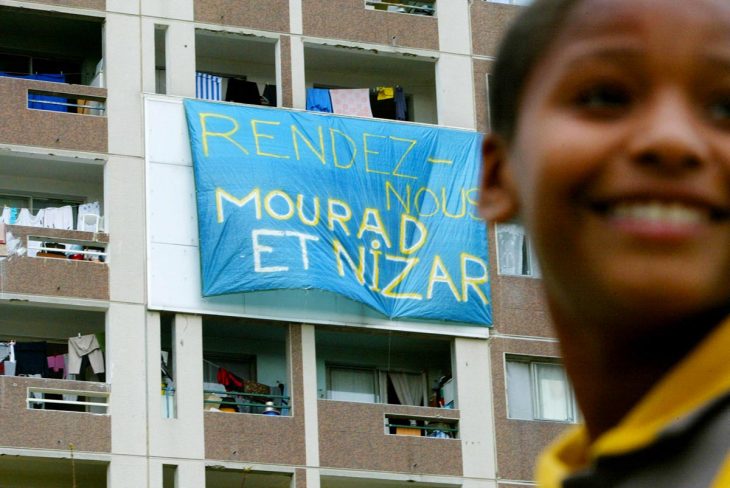

On January 13, 2021, in the case of Nizar Sassi and Mourad Benchellali, two French nationals detained at the US prison of Guantanamo Bay, the Cour de Cassation – the highest French jurisdiction – recognized that former president of the United States George W. Bush and various government officials were in fact “likely to have participated, as authors or accomplices” in the alleged crimes of torture and arbitrary detention in the context of the counter-terrorism operations following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

However, and “no matter how serious”, these crimes are, according to the French court, to be considered as falling within the exercise of state sovereignty (also called “acts of state”) which in the case of state agents and “given the state of international law (…) do not constitute exceptions to the principle of immunity from jurisdiction”.

The principle of immunity is the main and most controversial obstacle to prosecution. It is justified by either the nature of the crime or the official function (in the sense of "organs and entities that constitute the emanation of the state”) of the alleged perpetrator, the main criteria being whether or not the acts can be considered as the expression of state sovereignty versus mere “acts of management”. In line with that reasoning, immunity was denied in France in a 2015 case filed by Transparency International against the Vice President of Equatorial Guinea who had been charged with money laundering and corruption, acts considered as “committed for personal purposes “. Paradoxically, in the case of Rwandese national Pascal Simbikangwa, no immunity was ever considered.

Filed in November 2002 by French lawyer WiIliam Bourdon, the Guantanamo case went through several phases: from clear reluctance to investigate, to serious efforts to move it forward, despite the open resistance of the US administration to cooperate. Bourdon was later joined by the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights and the Centre for Constitutional Rights which have been proactively engaged in similar strategic litigations in other European countries (including in France against Donald Rumsfeld) as well as before the International Criminal Court. The Cour de Cassation considered that further investigation and collection of evidence about the Bush administration’s interrogation and detention policies was not necessary since they “cannot be prosecuted or indicted or subjected to arrest warrants”. The issue of whether the two French ex-detainees’ the right to a fair trial has been violated is being taken to the European Court of Human Rights.

The 2021 French ruling is in blatant contradiction with the now well-established rule of customary international law that immunity should not extend to international crimes such as torture. This is a norm of international law from which there should be no derogation under any circumstances.

As the US prosecutor Robert Jackson pleaded on 21 November 1945 before the International Military Tribunal of Nuremberg, “the idea that a state, any more than a corporation, commits crime, is a fiction. Crimes are always committed only by persons… It is quite intolerable to let such a legalism become the basis of personal immunity… Modern civilization puts unlimited weapons of destruction in the hands of men. It cannot tolerate so vast an area of legal irresponsibility”.

Acts of torture, as the 1999 Pinochet case reaffirmed, shall never be considered as being committed in the official capacity of a Head of State, and their alleged perpetration is sufficient to dismiss any immunity “because the offenders are common enemies of all mankind and all nations have an equal interest in their apprehension and prosecution”. Similarly, before the Extraordinary African Chambers in Senegal, Hissène Habré was indicted and later convicted for crimes against humanity, torture and war crimes even though his crimes were committed while he was the sitting head of state of Chad.

Ruling that acts of torture fall within the remit of sovereign acts-of-state is simply appalling.

“Germany will not be a safe haven”

While the highest French jurisdiction was granting immunity to former state officials alleged to have ordered the commission of torture, a few days later, on 28 January 2021 the German Federal Court of Justice (BGH) found that, on the contrary, state officials do not enjoy immunity from foreign criminal jurisdictions for war crimes and other crimes under international law.

The BGH was asked to decide whether the court could rule on acts "committed by a defendant in the exercise of foreign sovereign activity", in this case an Afghan military officer alleged to have mistreated three captured Taliban fighters during interrogation and had the body of a Taliban commander hung up like a trophy.

To take an informed decision, the German Court analysed the current state of international law vis-à-vis jurisdictional immunities, including a 2012 decision of the Swiss Federal Court which found that former Algerian defence minister Khaled Nezzar did not enjoy functional immunity for torture and crimes against humanity, and similar cases in Belgium and Spain illustrating that holding an official function is not an impediment to prosecution.

The German Court upheld that the “act-of-state doctrine” does not apply to international crimes, reiterating the Adolf Eichman decision of the Supreme Court of Israel which “using the ‘Nuremberg Principles’, held that the ‘act of State’ doctrine did not preclude criminal liability for violations of international law, in particular for international crimes such as crimes against humanity”. The German court concluded: “Germany was not, is not and will not be a safe haven for individuals who have committed crimes against the international community”.

In light of the above, the French ruling is archaic and contrary to customary international law. In what appears to be an opportunistic call to support its conservative views, the French court indicated that: “It is up to the international community to set the eventual limits of this principle [jurisdictional immunity] in the face of other values recognized by this community, including the prohibition of torture”. With a new session of the United Nations International Law Commission under way during which states are to discuss the “immunity of state officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction”, it should strongly be reaffirmed that functional immunity does not protect state officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction in respect of international crimes - genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, torture, enforced disappearance and extrajudicial executions.

© France 3

JEANNE SULZER

Jeanne Sulzer is a lawyer at the Paris Bar. She has been representing victims of international crimes before national, regional and international courts, including the International Criminal Court, for over 20 years. In France she has worked on cases of "universal jurisdiction" and in Senegal on reparations claims before the Extraordinary African Chambers. In Cambodia, she worked with the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia to deal with civil parties. Formerly in charge of the international justice office at the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), and in charge of legal analysis and positioning at Amnesty International France, she is currently advising the United Nations on the development of a normative legal framework on the rights of victims of terrorism.