Is the personal immunity enjoyed by heads of state in office absolute? Or can there be exceptions when the alleged acts constitute the most serious international crimes? The question raised before the French court of cassation, which met on Friday 4 July in Paris in plenary session – its most solemn form – is undoubtedly of particular importance in an international context where other sitting heads of state are subject to arrest warrants and where, until now, their immunity is the rule of law.

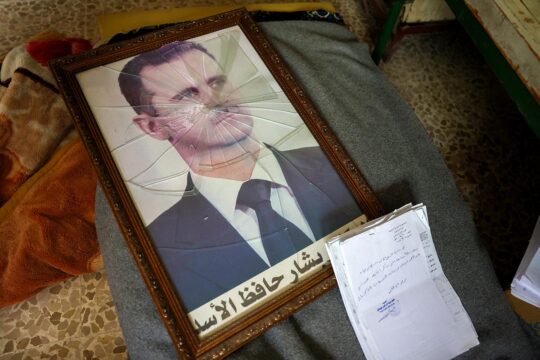

In June 2024, the investigating chamber of the Paris court of appeal ruled otherwise, validating an arrest warrant issued against Syrian president Bashar al-Assad as he was in office in 2023. The 19 judges of France’s highest court must now rule on the legality of this warrant.

According to the international custom, personal immunity protects a head of state, a head of government or a foreign minister in office from national courts. It lasts for the duration of their term of office and covers all acts that could be held against them, whether in a private capacity or in the name of state sovereignty. Functional (or material) immunity protects all state agents who have committed acts in the exercise of their functions and in the name of state sovereignty from foreign national courts, even after they have ceased their functions.

National warrant against Assad: a first

The case began in March 2021. A complaint with civil party status was filed in the Paris court by various organisations and several victims of the chemical weapons attacks committed in August 2013 in Eastern Ghouta, east of Damascus, where sarin gas bombings attributed to the regime caused more than a thousand deaths. In November 2023, two investigating judges finally issued four arrest warrants. One of them was for the current president, Bashar al-Assad, for complicity in crimes against humanity and war crimes. This was a first.

But the warrant was contested. First by the national anti-terrorism prosecutor’s office, responsible for prosecuting international crimes in France, which filed a motion to have the warrant overturned before the Paris court of appeal. Then by the general prosecutor’s office of the court of appeal. Considering that “the prohibition of the use of chemical weapons is part of customary international law as a peremptory norm”, the investigating chamber had ruled that the crimes alleged against Assad “could not be considered part of the official functions of a head of state”. And that the United Nations Security Council had adopted resolutions demanding that the perpetrators of chemical attacks in Syria be prosecuted, regardless of their position.

The decision of the investigating judges was “historic”, according to lawyer Jeanne Sulzer, who represents several civil parties, since case law had never allowed for exceptions to personal immunity. A judgment of the court of cassation, handed down in September 2020, simply ruled that if there were exceptions to this immunity, “it was up to the international community to define them”. “But immunity is entirely a matter of customary international law”, the lawyer told Justice Info; that is, the practice of states which, together, form custom. In other words, “the judge of immunities is the judge of the national courts”. And it is up to them – in this case, those of the court of cassation – to draw the possible new contours of this custom.

Immunity, the guarantor of state sovereignty

On Friday, the public prosecutor at the court of cassation, Rémy Heitz, questioned the grounds for the decision. While there is no doubt about the classification of the crimes alleged against Assad, “was it possible to set aside the Syrian president’s personal immunity in order to hold him criminally responsible?” No, says Heitz. In his view, considering that these crimes were “separable” from his functions “cannot be accepted” in view of the “sovereignty” and the “equality” of states, which “requires that no state can have authority over another” through the courts.

Heitz goes on to explain that he does not support a “general questioning” of the personal immunity of sitting heads of state. He argues that it guarantees “respect for the sovereignty of states”, prevents “abusive or politically motivated prosecutions” and ensures “the stability of international relations”.

However, national courts “are now an integral part of the international criminal justice system”, argues Paul Mathonnet, who represents all the civil parties before the court of cassation. He defends the idea that “the fight against impunity” is no longer considered, in international law, “as a mere value awaiting enshrinement by the will of the international community”. Rather, it is “a legally protected interest that binds the states”. In particular, considering that many crimes “remain outside the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC)”, as in this case, the lawyer points out, since Syria has not ratified the Rome Statute.

For the civil parties, the issue at stake is being able to “reserve the right to waive, on a case-by-case basis”, the personal immunity of a sitting head of state when he or she is accused of the most serious international crimes. And thus to establish an exception to its absolute nature. In particular, the lawyer continues, if this immunity leads “in practice to a situation of impunity, as the Pre-Trial Chamber found in its decision”. Choosing “conditional immunity”, he told the judges, would guard against the risk of a proliferation of situations of impunity, but also against the risk of proceedings being used “by ill-intentioned States”.

The appeal examined by the court of cassation is part of a “broader context”, according to Sulzer: "Personal immunity can be seen as a guarantee of a peaceful world, with respect for the sovereignty of states. But the opposite can also be said, and it can be argued that decimating one’s population is not exactly conducive to peaceful international and diplomatic relations”. For the lawyer, the question of immunity must also be assessed in light of its application, including in the context of states’ cooperation with the ICC, which does not recognise personal and functional immunities: “Many States consider that they cannot – or do not wish to – use their coercive power to arrest sitting leaders prosecuted by the ICC. This is because, for them, the question of immunity arises”, and it would still be difficult to address. Sometimes for obvious diplomatic reasons.

But things are changing: “Until now, touching personal immunity was taboo. When the investigating chamber handed down its ruling, we expected a kind of outcry. Almost to our surprise, we received an enormous amount of positive feedback, particularly from academics and professors of international law. These are progressive people, of course, but if it doesn’t hold, they do speak out.”

The attorney general’s third way

However, the attorney general proposed to the court of Cassation that it should not overturn the investigating chamber’s ruling and invited the judges to validate the arrest warrant for Assad. A kind of “third way”. More precisely, Heitz proposes to set aside the question of the former Syrian president’s personal immunity, considering that he has not been recognised by France as the legitimate head of state of the Syrian Arab Republic since 2012. He adds that this position is supported by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, whose opinion he sought.

The fact that Assad has not been in office since 8 December 2024 has no bearing on the proceedings, the reporting judge told the court, since “the validity of the arrest warrant must be assessed on the date it was issued”, in November 2023. The former head of state is thus the subject of another arrest warrant issued by French investigating judges in January 2025, which is not being contested by the public prosecutor’s office.

The argument that Assad’s immunity should be lifted on the grounds of “dis-recognition” was also put forward by the lawyer for the civil parties – an argument that should only be considered “if” the judges of the Court were not to accept “the case-by-case approach” proposed in the first instance, Mathonnet stated in court. In November 2012, French president François Hollande had announced that "France now recognises the Syrian National Coalition as the sole representative of the Syrian people”. But what would be the legal scope of a decision based on “dis-recognition”? asked the lawyer. Would it have “an effect” on international custom? Or would it be “solely” an assessment of whether “the person being prosecuted is indeed a head of state”?

“We welcome the fact that the public prosecutor’s office at the court of cassation is on the side of the victims and is seeking confirmation of the arrest warrant”, says Clémence Witt after the hearing, alongside two other representatives of the civil parties during the investigation, Sulzer and Chloé Pasmantier. Because following this path of dis-recognition would also mean following its reasoning, adds Sulzer; “and the reasoning for dis-recognition is mandatory due to the nature and gravity of the crimes” alleged.

“While it is interesting to note that the public prosecutor’s office before the court of cassation has adopted one of our arguments”, added Pasmantier, “it is also interesting to note that it is using it to avoid having to answer on the issue of personal immunity. Of course, civil parties would have liked the public prosecutor’s office to go even further by admitting the inapplicability of personal immunity in cases of crimes against humanity”.

As to whether Assad could have benefited from functional immunity, this is unlikely; international case law has evolved and now favours the introduction of an exception to its application in cases of war crimes and crimes against humanity. On Friday, the court of cassation examined another request on this issue, together with the case concerning the Assad’s arrest warrant.

The court of cassation’s decision will be handed down on 25 July.

WHAT THE PARIS ASSIZE COURT HAS SAID

A year ago, at the end of the first “Syrian” trial held, in absentia, in France, following a complaint about the enforced disappearance of two members of the Dabbagh family, the Paris assize court ruled in its written statement of 30 May 2024 that Bashar al-Assad “enjoys the immunity recognised by the international community for all heads of state”, but that “the same does not apply to the three defendants” in this trial. “The court considers that crimes against humanity, considered the most serious crimes in the hierarchy of crimes, cannot be covered” by functional (or material) immunity “also recognised by international law for all public officials for acts committed in the exercise of their functions”.