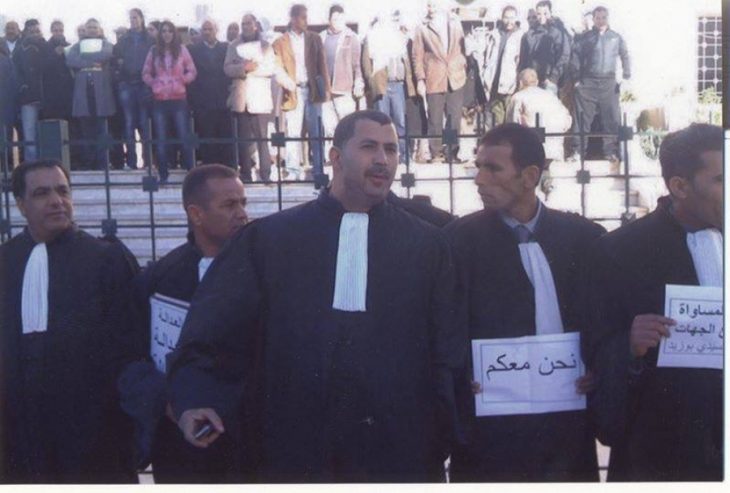

Lawyer Khaled Aouinia, big and tall at 45, has the passionate, determined, powerful voice for tough arguments in court. Before the Tunisian revolution he got himself noticed for voluntarily taking up the most “indefensible” causes in the time of the dictatorship. They included the Salafists of Soliman (40 km from Tunis) in 2006 and trade unionists from the mining region of Gafsa, southern Tunisia, in 2008. He led a group of lawyers close to the Tunisian Left and grassroots labour unions who rallied to the cause of the Sidi Bouzid uprising that followed the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, a 27-year-old street trader, on December 17, 2010. The population still remember that day December 24, 2010, when nearly half the town’s lawyers, about 50 of them, organized a protest in their black robes around the Justice Palace to protest rising police violence against demonstrators. Khaled Aouinia was an active member of that spectacular sit-in, broadcast by France 24 the same evening of December 24, five years ago.

Free Counsel

“To each period of events its tools of action,” says Khaled Aouinia. “In the days after Bouazizi’s suicide, some of us took to the streets in civilian clothes or in our lawyers’ robes to wave banners against the Ben Ali regime and for independent justice. Today we are part of the Network of Justice Observers set up by the Order of Advocates and Human Rights League, and we get support and lobbying from pressure groups like Lawyers Without Borders (ASF) and the World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) to help us move freedom and human rights forward.”

Aounia has joined a pool of lawyers initiated by ASF and OMCT, along with Moez Salhi, Tahar Kaddachi, Iadh Amami and Samah Brahmi, all lawyers in this dissident region of Sidi Bouzid and all aware of the injustice long suffered by this isolated region. The project named Adela (meaning justice in Arabic) was set up in April 2015 and is entirely funded by the UN Development Programme (UNDP). It seeks to improve access to justice for people in vulnerable situations, such as victims of the dictatorship, torture victims, the unemployed and victims of sexual violence. It also helps people involved in civil law cases who do not have the means to pay for legal counsel.

This group of lawyers listens, gives legal advice and information about transitional justice. It also provides free legal counsel by its lawyers who are voluntarily committed to human rights causes and have been trained by ASF, OMCT, the Arab Human Rights Centre and Danish anti-torture group Dignity to handle torture and restorative justice cases.

The Challenge of Torture Cases

Diplomas in transitional justice provide a substitute for decoration on the walls of Tahar Kaddachi’s tiny office in a small street in Sidi Bouzid town centre. The place looks much more like a spice shop than a flourishing lawyer’s office like those in the capital Tunis. Along with Khaled Aouinia and Moez Salhi, 30-year-old Kaddachi specializes in torture-related trials. Such cases are a big challenge as they are fraught with obstacles and irregularities, and hardly ever reach a conclusion.

“The obstacles start piling up at once,” says the young lawyer, “starting with the State Attorney General who tries to put us off pursuing the case, the doctor’s report that has got lost, botched initial proceedings and investigations by magistrates that go on for ever.”

Like a constantly erupting volcano, the Sidi Bouzid region has not stopped rising up since December 17, 2010, for the same reasons that Mohamed Bouazizi killed himself: marginalization, poverty and despair. Its educated but unemployed youth, whose situation has not changed despite the promises of the new political authorities, have continued to demonstrate and wave banners against the system. The police respond violently as they did under the dictatorship, carrying out night raids, heavy-handed interrogations, inflicting physical violence on those who “disrupt public order” and taking legal action against them. Eleven young people from Menzel Bouzayane (50 km south of Sidi Bouzid) were subject to such treatment after a September 26, 2012 protest they organized against their region’s exclusion from development programmes. Their cases are still in the works…

"Identified by a Tattoo"

At 5.00 in the morning a commando from the national guard launched a raid on the house of Ramzi, 32, asphyxiated him with tear gas, beat him up brutally targeting his handicapped leg and committed acts of torture on him during his detention. The doctor’s certificate has not yet been sent to the judge. Three years later, the court demanded a medical report. “But what evidence remains now of the violence inflicted on him?” asks Tahar Kaddachi.

Lawyer Moez Salhi, 43, who remained by Khaled Aouinia’s side during the turbulent years, encounters the same difficulties in the 15 torture cases he has undertaken as part of the Adela project. Some date back to January 2011, during the revolution.

“The judge always confronts you with the same argument, that it is ‘impossible to identify the people implicated in torture’,” says Salhi. “But I have given the investigating magistrate the name of a police chief accused of torture by one of my clients, and even described a tattoo on his arm to identify him. But it has so far been in vain.”

The code of silence plus a general law on impunity are always applied when it comes to allegations of torture by agents of the State, despite the fact that Tunisia has recently signed international conventions to end serious human rights violations.

Are the lawyers of Sidi Bouzid condemned like Sisyphus to a constant, fruitless struggle against the practice of torture in Tunisia?

An opening in the judicial system

“No,” say Khaled Aouinia and Moez Salhi in unison. “There has been some progress thanks to our determination and lobbying of the judicial authorities by groups such as ASF and OMCT. We have got them to agree that questioning of the victim is not done initially by police in Tunis but in Sidi Bouzid, so as to spare victims of torture from fatigue, waiting time and travel expenses. The investigation is then to continue at the police post where the victim suffered psychological or physical abuse. Is it possible, we argued, that the adversary in this case also be the investigator? So we have got the investigation put under a more or less neutral party, namely a magistrate.”

Even if many torture-related cases still get lost in the obscure corridors of the courts and accused persons are acquitted despite evidence, lawyers in Sidi Bouzid, who now work in a network, are full of hope for the future. They know that a new space has opened thanks to civil society’s post-Revolution vigilance and monitoring of the formerly opaque judicial system.

And five years ago, these black-robed lawyers also won another battle, kindling the spark that led to the flight of a powerful dictator.

Who would have believed that?