In the aftermath of the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis of Rwanda, between April and July 1994, the Rwandan State was destitute. In the midst of their razed homes, gutted towns, hills full of mass graves, deserted land and devastated infrastructure, were thousands of survivors, including orphaned children and babies, sick people who were hungry and homeless. The State had been emptied of its resources, looted to the last cent by members of the former government who had fled to neighbouring Zaire (today's Democratic Republic of Congo). Those who took power and stopped the genocide were faced with a seemingly impossible conundrum: how to help these survivors rise from the depths and provide for their basic needs to enable rehabilitation?

A first step was taken under the August 1996 Organic Law on the Punishment of Genocide as the first trials of genocide suspects established the responsibility of the Rwandan State. The courts ordered the State to pay colossal sums for the genocide committed in its name. The authorities recognized the principle of State continuity, and since the crime was committed in its name, the government agreed to pay each year not damages but a percentage of its annual budget to the Genocide Survivors Assistance Fund (FARG) for the most destitute. According to the law that created the FARG, it is funded mainly by the payment of 6% of the annual national budget, or more precisely by internal revenues. Before the amendment of this law, in 2008, every employee in the public or private sector had to make a contribution equivalent to 1% of their gross salary. But the fund may also receive contributions from local and international partners, local or international organizations and associations, individuals and entities.

Imararungu, the cow that breaks solitude

Dancilla Mukankusi survived the massacre in Kabarondo, a church in eastern Rwanda in which more than 2,000 Tutsi refugees, including her entire family, were killed within half a day on April 13, 1994. Today, at 63 years of age, she suffers from all kinds of illness including hepatitis, kidney failure, cardiovascular disorders and other chronic diseases. Even for her neighbours, she is the one who "spends more time in a hospital bed and lives on medication". Dancilla acknowledges this, saying she believes that "without the help of the FARG, I would already be dead". In addition to medical care, she receives a small, direct money allowance that helps her to survive as best she can.

In the neighbouring district of Rwamagana, Odette, 67, another widow of the genocide, lives in similar conditions to Dancilla. When asked how she deals with loneliness, she answers that she has a companion. "Who is it?" people ask her. Laughing, she goes to a small stable and whispers in the ear of a big cow munching on grass whose name is “Imararungu”, meaning the one who breaks solitude in the Rwandan language. Odette describes her day. Caring for Imararungu takes almost all her time from morning to night, like "a beloved child, a good companion that AVEGA gave me". AVEGA is the Association of Genocide Widows, a partner of the FARG in the rehabilitation of genocide victims.

For the neighbours, her real name doesn't matter, she's "the old lady with the FARG cow". But for Odette, "Imararungu takes the place of all the cows looted and slaughtered" during the genocide. And she is a great comfort. The cow, traditionally perceived as a sign of privilege of the Tutsi herder, was targeted during the genocide with a rallying song called "Let's eat the Tutsi cows". Odette is one of 7,510 widows who have received a cow since the Fund was set up.

Satisfying results

FARG's commitment to ensure the socio-economic rehabilitation of genocide survivors, against the backdrop of already existing programmes, operated along five main lines: providing medical care to the sick, direct assistance to the most vulnerable, facilitating education for thousands of children including several orphan heads of household, housing for all homeless people, and assistance in creating income-generating activities. According to a report drawn up in June 2018, i.e. after 20 years of operation, the fund has paid for medical care on over 2 million occasions, including for 428 patients treated abroad, at a total cost of nearly 19.5 billion Rwandan francs (19.3 million euros). Nearly 110,000 children and orphans have benefited from the education programme, at all levels and up to university. "It is a great pleasure to be able to help the lives of people who have been put at risk and made vulnerable by the genocide. We are satisfied with the results," says Théophile Ruberangeyo, Executive Director of FARG, who believes that some of the Fund's beneficiaries have completed all stages of the programme, namely "rehabilitation, reintegration and graduation". "From yesterday's orphans, we have made men and women who are responsible family members and citizens," he says.

The Fund has also enabled construction of some 45,000 housing units, some of which are in "reconciliation" villages where victims and former perpetrators live together, and has supported some 54,000 beneficiaries of income-generating activities. With the help of the "One dollar campaign", a project launched by the Rwandan diaspora, a large building in Kigali houses some 192 students orphaned by the genocide, formerly homeless and forced to spend the holidays in their schools.

In almost 20 years of operation, the approximately 272 billion Rwandan francs (270 million euros) spent by the Fund in all its areas of intervention are only "a drop in an ocean of problems", according to Théophile Ruberangeyo. Because, he says, this amount remains derisory in relation to the needs and the number of victims.

Many criticisms

The Fund has also faced many criticisms: embezzlement, houses built in a shoddy way to last only 5 to 10 years, corruption in the selection of beneficiaries, even allowing former militiamen to benefit. In 2010, following an assessment, more than 17,000 cases of malpractice were detected and 47 dishonest entrepreneurs identified and brought to justice.

But the challenges are not limited to the Fund’s operations. Already in 2009, the genocide survivors’ organization Ibuka [meaning “remember” in the Rwandan language], denounced the fact that, instead of compensating victims, the State opted for the creation of the FARG for which "even the victims are condemned to pay for their own reparation", according to Denis Bikesha, law professor at the University of Rwanda. "Reparation for victims must be understood as a right and not a favour," he says.

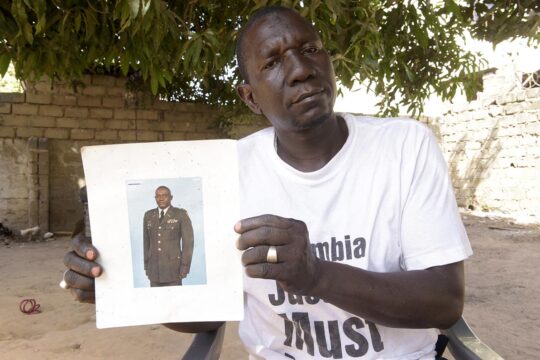

During a meeting of genocide survivors in December 2018 in Rusizi, southwestern Rwanda, participants were no more lenient. Genocide or not, they say in essence, does the State not have an obligation to provide for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged? "We want our rights, not favours," said Laurent Ndayambaje, local president of Ibuka. Although the FARG does good things for "our widows, orphans and all the vulnerable," he says, its services are perceived as "a favour to ask for and a favour to grant”. With the organization of the trials - hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were tried for their participation in the genocide, notably through community courts called gacaca - we got "the truth" and "the guilty parties punished," Ndayambaje admits. But for justice to be rendered in full, he says what is necessary is "just a small step towards reparation, even symbolic".

As a retired former parliamentarian concludes, for a State "it is easier to organize than to stop a genocide and/or to repair its consequences".

IMPOSSIBLE REPARATION

Who has a right to reparations? Victims who have filed a complaint in a legal case or all persons identified as victims at the community level? Who carries the responsibility for providing reparation -- individuals convicted and sentenced, the Rwandan State or the international community? These questions were asked in the wake of genocide in Rwanda, but are still being asked.

According to the 1996 Law on the Prosecution of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity Committed between 1 October 1990 and 31 December 1994, victims may file a civil suit and claim compensation for physical or moral damage. Within each court of first instance, a specialized chamber is then created to handle these cases. As a result, individuals and the State have been ordered to pay huge sums of money in damages. However, very quickly, the enforcement of these judgments came up against two major obstacles: the insolvency of the convicted and the impossibility for the government to fulfil this colossal obligation whilst also organizing its assistance to the most deprived survivors, in particular through the Genocide Survivors' Assistance Fund.

“A major denial of justice”

Drawing lessons from the specialized chambers, the Gacaca People's Courts Act did not provide for the possibility of a civil action. In these courts, persons convicted of offences against goods and property are simply required to repair or return them. No damages for a woman widowed as a result of the genocide, no damages for an old man made destitute after his children were killed in 1994, no damages for a person disabled for life as a result of wounds inflicted during the massacres.

The same deficiency was also present at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), set up by the United Nations in Tanzania and which closed its work at the end of 2015. Jean-Pierre Duzingizemungu, President of Ibuka, the main organization of genocide survivors, denounced this before the ICTR officials during the 20th commemorations of the genocide in April 2014. "For survivors, reparation means restitution and compensation for moral and material damage, rehabilitation and guarantee of non-repetition," he said. For Naphthal Ahishakiye, Executive Secretary of Ibuka, this legal vacuum at the ICTR and in the Gacaca constitutes, for the survivors, "a major denial of justice". "All in all, it's as if all the judicial bodies didn't want to render us justice," he concluded.

At the end of the Gacaca in 2012, a law was planned on the exercise of claims. Six years later, it is no longer even discussed. Some 69,000 cases out of the 2 million enforceable judgments reportedly issued, are still pending. This is a real headache for the Rwandan Justice Minister who, at the end of January, relaunched for the umpteenth time the campaign to raise awareness on the return of property looted and destroyed during the genocide. Another "hide-and-seek game", says one survivor in Kigali.