The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia face significant challenges as they reckon with the crimes of the Khmer Rouge

-

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) were established in 2006 as a “mixed” domestic and international body within Cambodia’s court system, following an agreement between the UN and Royal Government of Cambodia

-

The ECCC has delivered three guilty verdicts, finding Khmer Rouge leaders responsible for crimes against humanity

-

Further prosecutions against other Khmer Rouge figures have faced opposition from the Royal Government of Cambodia on the basis of the risks to national reconciliation

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) were established in 2006 based on an agreement between the UN and Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) to prosecute crimes perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge ‘Democratic Kampuchea’ regime between 1975 and 1979. During the years of Khmer Rouge rule an estimated 1.7 million people perished from starvation and disease or were executed. The Khmer Rouge attempted to establish a classless agrarian society. Urban centres were evacuated and city populations deported en masse to rural cooperatives. Religion was prohibited and money was abolished. The Khmer Rouge also treated ethnic minorities particularly harshly, with the Vietnamese, Cham Muslim and Khmer Krom communities facing severe persecution. The Khmer Rouge were removed from power in early 1979 by Vietnamese troops and rebel Cambodian factions, though relief from the Khmer Rouge regime also marked the inauguration of a bloody civil war that only ended in 1999.

Today the ECCC is the centrepiece of Cambodia’s efforts to redress and acknowledge its experiences of political violence. The ECCC integrates the work of local and international institutions, thus representing an important case within wider international justice initiatives because of its hybrid composition. The court is established as a special mechanism within Cambodia’s existing domestic court structure, and provides judgements through a ‘super majority’ formula between international (UN appointed) and domestic judicial staff. The localisation of the ECCC process means that judgements and findings are not remote from victim constituencies, while the place of (experienced) international staff in the process was thought to offer a capacity building role for the court. Moreover, the ECCC has featured novel opportunities for victim participation as ‘civil parties’, though these have unfolded in uneven and increasingly narrow terms as the ECCC’s work has progressed, and pressure to expedite (already slow) proceedings has increased.

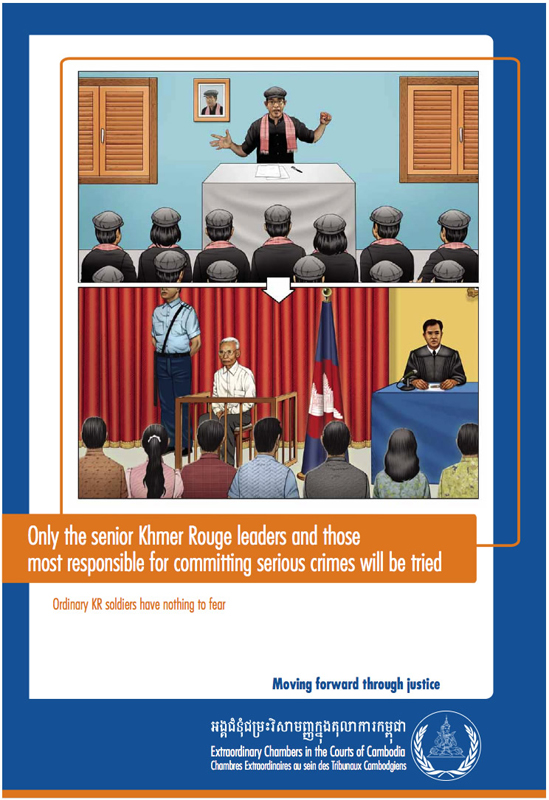

The ECCC is prosecuting “senior leaders” and “most responsible persons” for crimes committed during the Khmer Rouge years, including charges for international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The RGC intended the framing of the ECCC’s personal jurisdiction to encompass only a handful of individuals. On this basis, the limited personal jurisdiction reflects a longstanding politics of peace-building and reconciliation in Cambodia, bound to a history of amnesty agreements provided for lower and mid-level Khmer Rouge members during the civil war in the 1980s and 1990s. As the ECCC publicity poster specifically assures, lower level Khmer Rouge will not be prosecuted by the court. Lastly, as a principally retributive mechanism, the ECCC can dispense life sentences to guilty defendants, though the ECCC also has the capacity to issue “moral” and “collective” reparations to those formally recognised ‘civil party’ victims.

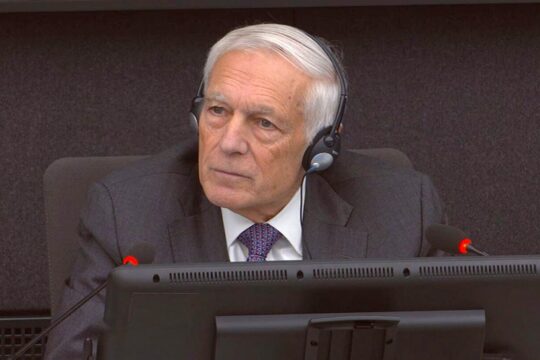

To date, the ECCC has worked on two cases, with investigations under way into a further two. In 2012 the former head of the ‘S-21’ security centre in Phnom Penh, ‘Duch’, was sentenced to life imprisonment having been found guilty of crimes against humanity in ‘Case 001’. A second trial against remaining members of the Khmer Rouge leadership, ‘Case 002’, was split into more manageable ‘mini’ trials in order to expedite proceedings. The first mini trial, ‘002/01’, focused principally on the evacuation of Phnom Penh in April 1975. In August 2014, 002/01 concluded when Nuon Chea (‘Brother No. 2’ second only to Pol Pot under the Khmer Rouge) and Khieu Samphan (the former Khmer Rouge head of state) were sentenced to life imprisonment following guilty verdicts on charges of crimes against humanity. The next phase of Case 002, which started in late 2014, will address the sensitive question of whether genocide was perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

The ongoing challenges facing the ECCC are significant. First and foremost, the ECCC has faced longstanding accusations of political interference, especially in regard to a final set of two prospective cases, 003 and 004. These two further cases focus on the role of “most responsible persons” under the ECCC mandate. Progress in both cases 003 and 004 has been slow and, as of January 2015, suspects in cases 003 and 004 have not been formally named. Crucially, both prospective prosecutions have faced serious opposition from the Royal Government of Cambodia. In 2010, Cambodian Foreign Minister Hor Namhong, referring to Prime Minister Hun Sen’s intention of not allowing Case 003, stated “we have to think about peace in Cambodia…”. For the RGC, prosecutions in Cases 003 and 004 are considered to be a threat to national reconciliation, and a violation of the terms under which they originally consented to the establishment of the ECCC. For international legal observers and human rights groups, on the other hand, the progress of Cases 003 and 004 is the key indicator of the independence of the ECCC, and is therefore crucial for its legacy as an effective intervention in international justice.

A second problem haunting the work of the ECCC is the ailing health of defendants. Two of the defendants initially indicted in Case 002 did not see their cases concluded: in November 2011, Ieng Thirith (the former Khmer Rouge Minister for Social Affairs) was “severed” from proceedings after being diagnosed with dementia and found unfit to face trial, while the former Khmer Rouge Foreign Minister and ‘Brother No. 3’, Ieng Sary, died in March 2013. A keen awareness among ECCC staff that the remaining defendant’s health was failing, alongside a sense of public frustration with regard to the slow progress of the ECCC’s work, informed the subsequent decision to break Case 002 into more manageable segments. Given that the ECCC is tasked with prosecuting crimes that occurred forty years ago, the problems attendant to defendants’ old age are inevitable.

The Cambodian case also raises important questions about the selectivity of international justice interventions. Given that international tribunals are predicated on normative obligations to prosecute all perpetrators of serious human rights violations, the delimitation of the ECCC’s mandate to 1975-1979 is striking in that it ignores episodes of serious violence and suffering before and after the Khmer Rouge were in power. Many Cambodians feel that the ECCC neglects an important contextual history of political violence. On the one hand, the political constraints of both the ECCC timeframe and personal jurisdiction reflect the way all international justice interventions emerge subject to political conditions and within both domestic and international hierarchies of power. On the other, we are reminded of Gregory Stanton’s argument that “perfection is the enemy of justice”, and that the prosecutions that have been concluded are already a better result than none at all.

The challenges facing the ECCC – particularly in regard to the ailing health of defendants, political interference, and a sense among sections of Cambodian society that a wider story about their experiences of political violence may be overlooked – help to explain continued efforts to rearticulate the key outcomes of the ECCC in terms of catalysing a process of “truth” seeking, as well as locating guilty verdicts as just one part of a wider portfolio of measures intended to redress the past. The promotion and foregrounding of outcomes beyond individual guilty verdicts reflects an increasingly pragmatic and tempered approach to expectation management on behalf of the ECCC (not to mention a reminder that punishments can rarely match the scale of the crimes in these contexts), as well as the pivotal role played by Cambodian civil society groups in supporting and complementing the work of the tribunal. The work of civil society organisations will significantly shape the future legacy of the ECCC.