Why is a second trial taking place in the Italian courts?

Nearly two years ago, Italy’s Court of Cassation (the country’s highest court) sentenced to life imprisonment fourteen former members of government, as well as of the military and security services of Uruguay and Chile, for their role in Operation Condor. Operation Condor was the codename given to the transnational coordination network that Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay established in 1975 to persecute dissidents beyond borders.

This landmark verdict, issued on July 9, 2021, marked the conclusion of proceedings that had begun two decades earlier, when Giancarlo Capaldo, of Rome’s Public Prosecution Office, launched investigations into the dozens of Italian citizens who were “disappeared” between the 1970s and 1980s. In 2017, through the first instance verdict, Rome’s Third Assize Court had become the first European tribunal to acknowledge the existence of the Condor organization and of its transnational repressive dynamics.

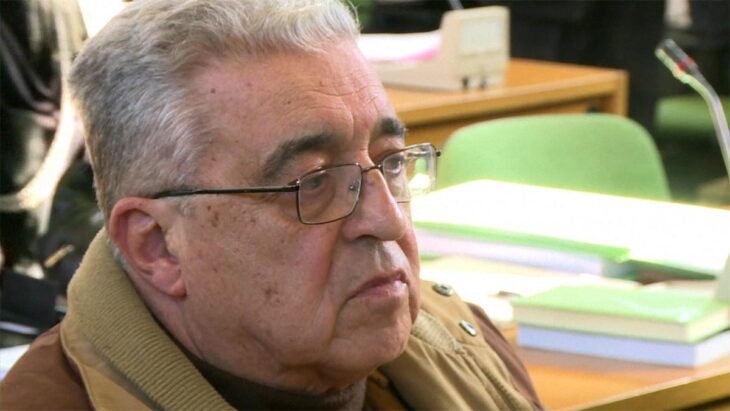

Amongst those condemned in 2021 was the Italo-Uruguayan former navy Captain Jorge Néstor Troccoli. He is currently serving a life sentence in an Italian prison for 26 murders. And it is this same man who is now on trial, once more, for the alleged murder of three other victims who disappeared in 1976 and 1977: Uruguayan Elena Quinteros, Italian Raffaela Giuliana Filipazzi, and her Argentine partner José Agustin Potenza. On May 5, 2022, the judge of the preliminary hearing, Annamaria Govoni, ordered the beginning of this second trial against Troccoli, again before Rome’s Third Assize Court. The first testimonial hearing took place on February 14, 2023, in the bunker courtroom of Rebibbia Prison, in Rome.

Who is Jorge Nestor Troccoli?

Jorge Néstor Troccoli was born in Montevideo [Uruguay] in 1947. He was a member of the Navy Fusiliers Corps (FUSNA), an elite operative unit of the Navy. His role in the Uruguayan repressive apparatus was already assessed and proven during the first proceedings in Italy. Between 1976 and 1978, Troccoli headed the FUSNA’s S2 section that specialized in intelligence gathering and also participated in abduction operations. During his career, he was involved in many operations against political opponents inside and outside Uruguayan territory. In the late 1970s, he was the liaison officer between the Uruguayan and Argentine Navy intelligence services. Between 1978 and 1979, Troccoli also served as an officer in the infamous task force 3.3 that operated at the Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (Navy School of Mechanics) in Buenos Aires, better known as ESMA, one of the main detention and torture centers that operated through the 1976-1983 Argentine dictatorship.

In the early 2000s, he obtained an Italian passport through his great-grandfather. With Italian citizenship, he hid in a small town in the province of Salerno, Marina di Camerota. Despite a late start in transitional justice efforts, by the mid-2000s Uruguay was belatedly beginning to conduct criminal investigations into the atrocities committed during the 1973-1985 dictatorship. But Troccoli’s escape was not enough to evade justice. In late 2007, he was in fact arrested as part of the Italian Operation Condor trials investigations. After being acquitted in first instance in 2017, he was eventually sentenced to life in prison by Rome’s First Assize Appeals Court in 2019, in a verdict later confirmed by the Court of Cassation. Troccoli is the author of a book, "The Wrath of Leviathan," in which he discusses the crimes he committed, framing them as acts in defense of his homeland.

New evidence on three victims

Albeit separate from the earlier trial, the new prosecution builds on the prior historic sentence. During the appeal stage of the first Condor trial, lawyers Andrea Speranzoni, who was at the time representing the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, as well as families from Chile, and Uruguay, and Alicia Mejía had traveled to both Uruguay and Argentina in the summer of 2018 in search of novel evidence that could be presented to the Appeals Court. While digging through the archives of FUSNA, they found novel evidence in Uruguay that paved the way for the new trial.

This new evidence mostly relies on the archival records of the three victims.

Elena Cándida Quinteros, who was a teacher and an active militant in the Uruguayan Anarchist Federation. In 1975, she had participated in the final Congress that had led to the creation of the Partido por la Victoria del Pueblo (Party for the Victory of the People, PVP) in Buenos Aires, which brought together Uruguayan exiles and catalyzed resistance efforts against the Uruguayan dictatorship from Argentina. Quinteros was in charge of counter-information and propaganda in Montevideo. On June 24, 1976 she was arrested at her home and taken to a clandestine detention place. A few days later, she convinced her captors to take her to the central Artigas Boulevard, pretending she was supposed to meet another militant there. In reality, she was seeking to escape and obtain asylum at the Venezuelan embassy in Montevideo, located nearby.

She managed to enter the embassy gardens. But her captors, violating the diplomatic premises, took her back and forced her into their car, which drove off to an unknown destination. A former FUSNA officer, Alex Lebel, has affirmed in the early 2000s in a Uruguayan military honor tribunal that Troccoli and another FUSNA officer, Juan Carlos Larcebeau, had participated in Quinteros’ abduction. Elena remains disappeared to date.

José Agustín Potenza and Raffaela Giuliana Filipazzi, who were kidnapped in Montevideo in 1977 by FUSNA agents and subsequently transferred to Paraguay through a commercial flight where they were murdered. Potenza worked at the Library of the National Congress in Buenos Aires and he had played an active role in the Peronist Resistance during the 1950s. Filipazzi, born in the Italian city of Brescia, arrived with her parents to Argentina when she was just over a year old. Unlike Potenza, she had no clear political militancy background. The couple was abducted at the Hermitage Hotel in Montevideo. From May 27 to June 8, 1977, they were detained at the secret prision that functioned within FUSNA’s headquarters in the Uruguayan capital. Subsequently, the Director of Foreign Affairs of the Capital Police of Paraguay, Victorino Oviedo, travelled to Montevideo to take Potenza and Filipazzi to Asunción. Their remains were found in a clandestine tomb on police grounds in 2013 in Asunción and formally identified in 2016.

A second step in justice seekers’ journey

There are two innovative aspects of this second criminal investigation into Operation Condor.

First, the Italian justice system decided to build a case for the murder of Argentine and Uruguayan citizens, not just Italians as in the previous trials. This was possible because the defendant in this case, Troccoli, is an Italian national. In the late 1990s, the prior Condor and Argentinian cases had, instead, relied entirely on the so-called “passive personality” principle; jurisdiction had been claimed on the basis of the nationality of the victims given that all of them were Italian citizens. Only in 2009, eighteen Uruguayan and two Argentine victims were "added" to the first Condor investigation after Italian authorities had in 2008 rejected Uruguay’s extradition request for Troccoli. Complying with the international law obligation to extradite or prosecute (the Latin maxim aut dedere aut judicare), Italy had to subsequently prosecute Troccoli for the charges he also faced in Uruguay, namely the non-Italian victims that had been comprised in the extradition proceedings.

Second, this new trial could be seen as a second step in justice seekers' journey. The first trial, in fact, aimed to unpack and comprehend the overall inner workings of Operation Condor and the key role of the top civilian and military leadership of South America’s dictatorships in setting up this regional system of borderless repression. The defendants included such emblematic figures as Luis García Meza Tejada and Luis Arce Gómez, dictator and interior minister of Bolivia from 1980 to 1981; Juan Carlos Blanco, Uruguay’s foreign minister between 1972 and 1976; former Peruvian president Francisco Morales-Bermúdez Cerruti and Manuel Contreras, the Director of the Chilean Directorate of National Intelligence.

Reconstructing the complex historical and political backdrop, the role of the masterminds of Condor, as well as the crucial responsibility of middle ranking officers which implemented the borderless terror plan, required a great deal of historical as well as judicial reconstruction work. That is why the trial began about 15 years after investigations had initially started in 1999. Moreover, some of the defendants were already under arrest and very elderly and some died during the trial, such as Contreras.

The beginning of the new process shows that the victims’ demands for justice and truth continue. Although the current trial has only one defendant, already convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in Italy during the first trial and thus already facing the most severe punishment under Italian law, this trial is still important to finally give justice to the families of José Potenza, Raffaela Filipazzi, and Elena Quinteros. Furthermore, the trial has the potential to explore and unravel further the key role of countries, such as Paraguay, that have so far largely failed to investigate the crimes committed by its own dictatorship and the part it played during Operation Condor.

At the same time, continuing the search for truth and justice, anywhere in the world, is a duty toward the entire societies that have experienced the atrocities of military dictatorships on their skin, as part of setting the ground for guarantees of non-repetition of similar crimes in the future. In addition, transnational repression of exiles and dissidents remains a major problem worldwide today, as reported by US think tank Freedom House. Justice for the crimes of Operation Condor is, therefore, a warning to current authoritarian states and a milestone for future global justice.

Francesca Lessa is a Lecturer in Latin American Studies and Development at the University of Oxford. She is also Honorary President of the Observatorio Luz Ibarburu in Uruguay. Her most recent book, "The Condor Trials: Transnational Repression and Human Rights in South America," published by Yale University Press in 2022, received the 2023 Méndez Book Award for Human Rights in Latin America and the honorable mention of the 2023 Bryce Wood Book Award of the Latin American Studies Association. She was called by Rome’s Public Prosecutor Office as an expert witness in the second Operation Condor trial on February 14, 2023.

Vito Ruggiero is a PhD in Latin American History from Roma Tre University. From 2018 to 2020 he was associate researcher at the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. In 2017, he carried out a research fellowship at the National Security Archive of Washington DC. He also collaborated with the Second Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry into the death of Aldo Moro, on behalf of which he conducted research in the Archives of Terror of Paraguay.