Several historical episodes have recently been at the centre of public debate in Greenland and Denmark, including adoptions of Greenlandic children by Danish families in the 60s and 70s and the so-called “judicial orphans”: lack of inheritance rights for Greenlanders born from unmarried Greenlandic women to Danish men. Now an investigative podcast has revealed yet another example of problematic guardianship from Danish authorities in Greenland: back in the 1960’s and 1970’s Danish health authorities placed thousands of intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUD) in Greenlandic women and girls to diminish population growth.

But contrary to prior years, the Danish government now proves to be more open to launch investigations into Denmark’s colonial past in Greenland. And the IUD campaign is to be part of a larger investigation of the relationship between Denmark and Greenland from the end of the Second World War until today.

The 1966-1974 IUD campaign

In 1953 Greenland, a former colony, had become an integral part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It was then administered by the Ministry of Greenland under the Danish government and an effective modernisation process was changing the country rapidly. The mortality rate dropped. In 15 years, the birth rate increased by almost 80 percent. By the 1960s, Greenland had the world’s highest birth rate, and about 50 percent of the population was under the age of 16. Approximately 25 percent of children were born outside wedlock. The construction boom was attracting a large number of Danish workers, resulting in a rise of pregnancies among young Greenlandic girls. In 1965, some 500 children were born of unmarried women, a third of them under the age of 20. In the capital, Nuuk, 50 percent of the infants were born of unmarried mothers.

The young mothers posed a problem for the modernisation process: the girls were intended to be educated and take part in it. Another concern for the Danish authorities was that the modernisation of Greenland would be more expensive due to the population growth.

In light of this, a family planning campaign was initiated in 1966. An IUD program was established in 17 medical districts. Between 1966 and 1970 half of Greenland’s fertile women, approximately 4.500, received IUDs, causing the birth rate to dramatically drop. The IUD campaign continued until 1974 but the number of IUDs in the 70s has not been registered so the total number is unknown.

Lowering the cost of modernization

It is this IUD campaign that was the topic of the investigative podcast Spiralkampagnen (“The IUD campaign”) by two journalists from the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR), Celine Klint and Anne Pilegaard Petersen. The podcast, released in May, revealed that some of the 4500 Greenlandic women and girls never gave their informed consent, and some women were even given an IUD after childbirth without their knowledge. A former doctor in Greenland, Hans Jørgen Fenger, explained that he was told by his superior at the hospital that for a period of time IUDs were placed routinely in female patients without the patient’s knowledge or consent. Another source described how doctors in Greenland joked that when a woman consulted a doctor for a swollen finger, she would leave the consultation with an IUD. After the publication of the podcast a gynaecologist in Nuuk told Greenland’s Broadcasting Corporation that they still today find IUDs in women who were unaware of them being there. “Only a few women who’ve just given birth left the hospital without a loop, and the same was true for women who had abortions,” Jens Misfeldt, a former doctor in Greenland, stated in an article in 1977.

Was the IUD and family planning campaigns motivated by a wish to protect young unmarried girls from becoming mothers? Or were they economically motivated? Did the Danish administration in Greenland wish to limit the explosive population growth to lower the cost of modernisation of Greenland? A 1970 speech in the Danish Parliament by the minister for Greenland A.C. Normann hints at the latter. “The fierce population increase meant that we had to increase our effort if we were to achieve improvements in living conditions,” he said, noting that the IUD campaign had contributed to the birth rate drop.

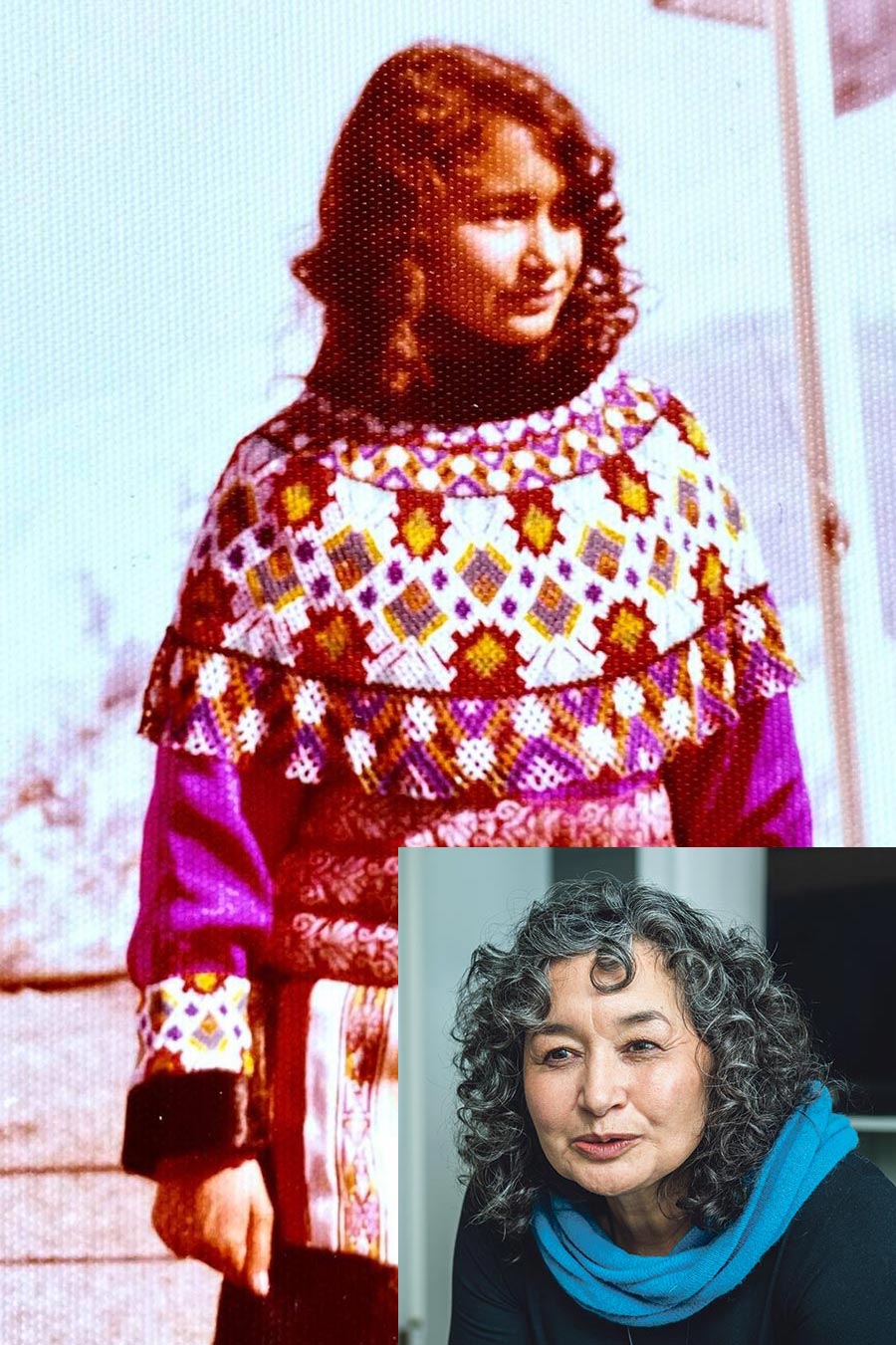

“The state took my virginity”

Naja Lyberth is a therapist specialised in trauma and a prominent voice in the debate on the IUDs. At 14 years old, she was one of thousands of young girls and women in Greenland who received an IUD. At the time, she was not yet sexually active. She remembers how all the girls in her class were told by the school doctor to go to the hospital to get an IUD. “They never presented it as a choice”, she says. The next day, one by one, they received an IUD. Lyberth is certain that her parents never gave permission for the procedure, and that her dad would have stopped it had he known. “The state took my virginity”, she says. After the procedure Lyberth, as many other of the Greenlandic women who have come forward, suffered from severe menstrual cramps and heavy bleeding. Some suffered complications with uterine infections.

Lyberth has established a Facebook-group for traumatised women who want to share their IUD stories. She has learned from them that many were unable to become pregnant due to complications after receiving the IUD. “It seems that the younger they were, the more complications and risk for infertility”, she says. Some of the women in the group were 12 years old when they received an IUD.

The contraceptive devices used in Greenland prior to the IUD campaign were diaphragms and condoms. Even though the contraceptive pill had been released in 1960 in the US and in 1966 in Denmark, the pill was not deemed appropriate in Greenland. In 1966, a study in Greenland about contraceptive methods was carried out. It argued that since the pill must be taken daily and that in North Greenland the sun doesn’t set in the summertime, women would be incapable of remembering to take their pill. It concluded that the summer activity of Greenlanders, who enjoyed spending two to three months in tents on fishing grounds, was not compatible with regularly taking the pill.

“Silent acceptance”

The IUD campaign was never presented to the Greenlandic country council (Landsrådet) which was the highest representative political body in Greenland at the time. The council did not have any formal power but functioned as an advisory board to the Danish authorities in Greenland. The podcast documents how Danish officials prepared notes for a 1974 meeting at the United Nations defending the family planning campaign in Greenland. In the notes, the Danish officials tried to argue that since the country council did not take actions against the IUD campaign, their passivity equaled a silent acceptance. After the meeting, the UN recommended that all countries make sure to honour individuals’ right to determine their own family planning. It stressed that systemised family planning should not be used as a motor to speed up a development process.

Today, it can be difficult to grasp why no one in Greenland publicly criticised the practice that affected so many women. Maybe an explanation can be found in the composition of the country council, which had only one woman out of 13 members. Or maybe contraception and a woman’s uterus was just not a topic for conversation. The women who suffered from complications due to the IUDs kept it to themselves.

The IUD campaign was not unknown to Greenlanders before the podcast was released. Professor Peter Bjerregaard from the Danish National Institute of Public Health briefly mentioned the IUD campaign in his 1991 doctor’s thesis where he connected the drastic drop in Greenland’s birthrate in the 60s to the IUDs and the family planning campaign. In 2019 the Greenlandic newspaper Atuagagdliutit published a story about the IUD campaign featuring Naja Lyberth. In 2021 in an article I wrote in the Greenlandic magazine Arnanut – in which Lyberth was also quoted – Kathrine Bødker, chairperson for Greenland’s Gender Equality Council, was quoted saying that she knew of the IUD campaign, herself being part of the much smaller generation that followed the campaign. The article caused an uproar on social media among young Greenlanders who had never heard about the IUD campaign, and several older women bearing witness to the story. But it did not have any political implications; the Greenlandic politicians remained quiet.

But the article inspired the two DR journalists and their investigative podcast led to a call for action - signaling that times have changed, and that many Greenlanders see it as about time to confront prior colonial practices and abuse in Greenland.

A new investigation

Reactions to the podcast have been harsh. “The case is completely absurd and should in no way be ignored or camouflaged. Call it what it is: Genocide”, Greenlandic MP in Denmark Aki-Matilda Høegh-Dam said to the Greenlandic news website sermitsiaq.AG. She argues that the IUD campaign falls under the UN definition of genocide for the crime of “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group”. Greenlandic MP Doris J. Jensen said that the disclosures are of such severity that the relationship between Denmark and Greenland should be reconsidered, thereby suggesting a future Greenlandic declaration of independence.

The government in Greenland, the two Greenlandic members of the Danish parliament as well as the Greenlandic parliament all called for a historical investigation on the IUD campaign. “The stories of the Greenlandic women have made a deep impression. The coverage by DR depicts a deeply problematic practice that seems completely incomprehensible today”, Denmark’s minister of Health said to DR. He promised his ministry would conduct an investigation.

In the spring of 2022, Danish prime minister Mette Frederiksen had officially apologised for the removal of 22 Greenlandic children from their parents in what was later named “The Experiment” – a failed attempt to educate a new Greenlandic elite by removing the children from their parents and bringing them to Denmark to learn how to speak Danish and understand Danish culture.

This is a dramatic change from 2013 when the Danish prime minister Helle Thorning Schmidt answered “We have no need for reconciliation”, to my question on whether Denmark would participate in the Greenlandic Reconciliation Commission.

At the National Assembly this year, Denmark and Greenland agreed upon initiating a new impartial investigation on the historic relationship between Denmark and Greenland from WWII until today. The research on the IUD campaign will now be included in this investigation.

Martine Lind Krebs is a journalist and an anthropologist, specialising in Greenland, where she grew up. Former editor of the radio and online news on KNR, the Greenlandic Broadcasting Corporation, and the Greenlandic magazine Arnanut. Today, she works as a freelance journalist and producer of learning materials on Greenland.