Last October, an Eritrean man wanted by Italian authorities on human trafficking charges was arrested by Interpol at Addis Ababa International airport as he was trying to board a flight to Australia. The man was extradited to Italy and is to be tried before a court of Catania, Sicily, where the first victims of his alleged organised network were disembarked.

This arrest is not an isolated case. A week earlier, another Eritrean accused of trafficking people to the Netherlands between 2014 and 2020 was extradited to the Netherlands. He is now facing trial in Zwolle, an hour away from Amsterdam. He is suspected of playing a leading role in a major international criminal network that smuggled Eritreans to the Netherlands.

These investigations were achieved through a joint international cooperation team set up in 2018 involving judicial and police authorities in Italy and the Netherlands, together with the United Kingdom, Spain, Europol, and since 2022, the International Criminal Court (ICC). They focus on tackling trafficking and crimes against migrants in Libya. Italy is the first destination for Libyan-based human traffickers who charge migrants hundreds or thousands of dollars for the dangerous Mediterranean crossing.

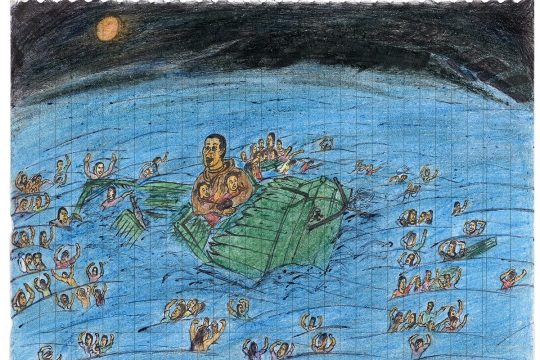

According to Médecins sans frontières (MSF), at least 600,000 migrants were stuck in Libya last year. In its June 2022 report it denounced human rights violations sometimes resulting in death that migrants suffer at the hands of traffickers and militia groups in Libya.

Trafficking business comes to trial

In the civil unrest that followed the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in 2011, criminal groups inside and outside Libya saw an opportunity for business, and trafficking became very lucrative. It was these money flows that Dutch prosecutors traced to build the case against the Eritrean trafficker known as Amaneul Walid, says Gerben Wilbrink, spokesman for the Dutch prosecutor’s office on the case. His gang, which he allegedly led with another Eritrean, Zekarias Habtemariam Kidane, who was arrested in Sudan on January 1, operated very violently, according to the public prosecution.

“The way the business model works is that they select people in Eritrea and they say, well, we can bring you to Europe if you pay us a lot of money,” says Wilbrink. But then people are put in trucks and unknowingly brought to Libya, where they are held in camps until their families pay the traffickers more money. If they cannot afford it, migrants are tortured, raped and held in the camps watched by armed guards. In one case, Wilbrink says, they “fired at people who tried to flee these camps”. Many casualties are reported in these detention centres, he adds. The Dutch could move forward on this case because of the large number of Eritreans in the Netherlands, who stated how money was extorted from them by Walid’s network for their relatives to be smuggled to Europe.

Money tracking was also at the centre of the case of the Eritrean extradited to Italy. The trafficker, Ghebremedin Temeschen Ghebru, was a “hawaladar”, says Italian public prosecutor Giorgia Righi. The hawala is a traditionnal informal money transfer system through which, in this case payments made by the relatives of those kidnapped are sent to the traffickers and then to their various intermediaries along the journey.

Atta, the Eritrean insider

The Eritrean criminal organisation that Ghebru allegedly led was trafficking migrants mainly from the Horn of Africa to Libya and then onwards to Italy and northern Europe, explains the Italian prosecutor. This network has been the focus of a wider operation called “Glauco 4” coordinated by the office of the public prosecutor in Palermo, where Righi works. “What sparked this operation was the 2013 shipwreck where 300 migrants lost their lives off the cost of Lampedusa, in Sicily,” she says. “That event led to more structured investigations.”

A turning point early in the case was information provided by the only Eritrean collaborator so far cooperating with justice – who was one of the leaders of the trafficking network in Libya. Righi shortens his name to Atta and explains how he provided details on other traffickers operating in Eritrea, Libya and the United Arab Emirates. Insider witnesses and informants have historically been key to the mafia trials, which also make Italy and especially Palermo experienced in handling organised criminal networks cases.

“From there we started with telephone tapping but also with searches and seizures, within Italy sometimes,” prosecutor Righi says. “Over time we have managed to reconstruct the criminal network of these organizations.” So far this operation in Italy has led to the arrest of 14 Eritrean traffickers. Righi expects the trial of Ghebru to last a few years, considering the slow pace of the Italian judicial system. The second hearing in the Dutch trial is already planned for April, and the case could be closed by the end of 2023 or 2024, says Wilbrink.

A well-established cooperation

The tragic 2013 shipwreck also served as the “initial impetus” for the creation in Europe of a joint team on crimes against migrants in Libya, recalls Nicole Samson, senior trial lawyer at the ICC office of the prosecutor. Informally started in 2015, the team was formalised in 2018 under the UN Convention on Transnational Organised Crime. “This cooperation is very important” underlines Righi. Each prosecutor runs its own investigation but, by sharing information, they can “achieve goals that we would not be able to achieve individually”, she explains.

As the first point of arrival for refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea by boat, Italy is well placed to collect testimonies. These have, for example, helped the Netherlands build a case against the Eritrean smuggler Kidane, Righi says, as Italy shared statements of migrants recognising him on pictures. After escaping from Ethiopian justice in 2021, Kidane was finally arrested in Sudan early this year as a result of an international police cooperation led by the United Arab Emirates with Interpol. The Netherlands has now requested his extradition.

Domestic limitations on international crimes

However strong the cooperation between countries can be, national prosecutions remain limited in prosecuting international crimes. “We would need a foot on the ground in Libya, which is not the case at the moment,” says Wilbrink when asked about the decision to charge Walid for membership of a criminal organisation and not for torture or sexual abuses. This limitation also would hold for the prosecution of crimes against humanity, where the evidentiary standards required are higher, says Wilbrink. Italy, for its part, has not incorporated crimes against humanity and war crimes in its jurisdiction.

However, numerous NGOs say that crimes against migrants in Libya amount to crimes against humanity. Imprisonment, killings, torture, sexual violence, persecution, enslavement, and war crimes against migrants held in Libyan detention centres were reported by the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) in 2021 in a first communication to the ICC. In 2022, a UN Fact-Finding Mission in Libya gathered evidence “providing reasonable grounds to believe that crimes against humanity” have been committed against migrants in Libya. In a second communication, the ECCHR underlined how the interception of migrants at sea and their placing in detention centres amounts to crimes against humanity.

This echoes the situation denounced in 2018 by the Director of the NGO We Are Not Weapons of War, Céline Bardet, of migrants suffering systematic torture and slavery being used both as weapon and victim of sexual crimes, which she said should lead to the long-awaited opening of a proper investigation at the ICC. Since 2011, when the UN first referred the Libya situation to the ICC, the hopes of victims have been unattended, as no concrete results could be seen at the ICC, said Céline Bardet interviewed last year. This is despite the fact that the former Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda was already talking of focusing on human trafficking back in 2016, a position confirmed by the current prosecutor Karim Khan in 2022.

ICC’s prosecutor renewed promises

In November, Khan visited mass graves in Tarhuna and expressed to the United Nations his intentions to renew its predecessor’s plans to start serious investigations in Libya. The ICC finally joined the joint European investigative team last September, in an effort to increase complementarity and support to national prosecutions, as the ICC has limited resources to intervene in all situations, says ICC prosecutor Samson.

Looking at the future, Italian prosecutor Righi says that one of the major goals of the joint team would be now “to reach a broad cooperation with the countries affected - first of all by the traffic, and therefore with Libya in the first place”. In the meantime, the controversial Memorandum of Understanding on Migration that was signed by Rome and Tripoli in 2017 and has since then provided the latter with financial and technical support to “combat illegal immigration” was automatically renewed on February 2, granting Libya more resources to intercept migrants at sea and potentially return them into the hands of trafficking networks.