“History sadly seems to be repeating itself,” said victims’ legal representative Natalie von Wistinghausen in her opening statement, evoking the renewed armed conflict that broke out in Sudan on April 15. It is “distressing”, she added, that that almost two decades after the events sparked the Hague trial “potential international crimes are occurring in Darfur right now”, and mentioned the death of civilians, looting and destruction of homes and livelihood and the displacement of tens of thousands of people.

On June 5, legal representatives for the victims made their opening statements in the first trial before the International Criminal Court (ICC) concerning crimes committed in Darfur (Sudan). Ali Muhammad Ali Abd-Al-Rahman, known as Ali Kushayb, is accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly committed between 2003 and 2004 in West Darfur. This is the first ICC case for war crimes in Sudan, which is not a state party to the court, after the UN Security Council referred the situation in Darfur to the ICC in March 2005.

The total number of participating victims rose to 600 earlier in May, after the latest group of 112 were admitted by the ICC. One witness and two victims appeared in court during this phase of the trial, which closed on Wednesday, June 7. One of them is a member of the wider diaspora and the other two live in refugee camps in neighbouring Chad. Two other victims living in internally displaced persons camps in Darfur were also scheduled, but were unable to move because in the current conflicts the borders are too unsafe and the Janjaweed are controlling the areas.

Abd-Al-Rahman allegedly led the government-backed Janjaweed militia in western Darfur between 2003 and 2004. According to prosecution, he helped with the recruitment and organization of the militia that engaged in an ethnic cleansing programme, and he directed attacks against four villages - Kodoom, Bindisi, Mukjar and Deleig. The defendant pleaded not-guilty to all charges and his defence argued that he is not Ali Kushayb. His trial began in April 2022, two years after he surrendered himself.

“Victims wish to return to their land”

“Victims seek justice, accountability, and of course recognition on behalf of themselves, their families and the wider Fur community”, which was targeted by the government, said von Wistinghausen. She added that “as a demonstration of the international community's commitment to stand against ongoing serious criminal and human rights violations and as a measure guarding against repetition”, many victims expressed the “strong belief that the process of justice is an essential component in seeking a resolution to the still ongoing instability and violence that plagues Darfur and ultimately a possibility for them to return to their ancestral land”. Victims repeatedly expressed their “wish to return to their land”, she stressed.

But on April 26, former President Omar Al Bashir, former Minister for Humanitarian Affairs Ahmed Haroun and Defence Minister Abdulraheem Mohammed Hussein got out of prison. This has sparked fear among the victims but also a renewed call that this trial be just a first step, said von Wistinghausen. And two decades after the crimes, victims are still mostly displaced. According her trial brief, the vast majority resides in internally displaced persons camps in Darfur. One of these is the Kalma camp, established in 2004 and home to more than 100,000 people. Another large number of victims live in refugee camps in Chad, while a smaller number is located in cities across Sudan. The remainder are parts of the wider diaspora.

“Emotionally, I am dead”

Born in Bindisi, Central Darfur, Hassan Hassan has lived in the Kalma camp, in Uganda, and is now in Ottawa, Canada, from where he addressed the court. Asked about his childhood in West Darfur, he described it as a “beautiful place” and talked about the great sense of community there. He was nine years old when the Janjaweed and the Sudanese militia arrived in Bindisi - they killed his father among many people and set fire to their houses. “It was horrible”. He pointed at his body, where he said scars are still visible from the time he was tortured by Janjaweeds. He fled and lived with his mother in Mukjar, West Darfur, where he said he witnessed murders and torturing of Fur people with burning charcoal and other means. Hassan talked about the visible and invisible wounds that remain 20 years after he survived a “genocide” and was forced into displacement. “I'm happy that I am still alive, but psychologically emotionally and mentally I am dead,” he said.

Like Hassan, 20 percent of the participating victims were children under 18 at the time of the events. Sexual and gender based crimes were carried out in a “brutal manner” and often out in the open, stressed von Wistinghausen in the opening statement. People were attacked, their property looted and they were “displaced from their ancestral land”, she said on Monday. One victim told her that “nothing was left”. Still today, many people suffer the physical and psychological consequences of being attacked and displaced, or of witnessing other members of the community or their loved ones murdered or captured.

“We are not representing a group of victims, we are representing individuals,” said von Wistinghausen in an interview for Justice Info, stressing the importance of listening to the victims’ different perspectives. To her, “the people we are representing are just a drop in the ocean of the number of victims that exist in Darfur”, but the wider population especially in the capital city Khartoum seemed very interested in this trial, before new violence broke out.

Contact with the victims in Sudan mainly happens via intermediaries on the ground, WhatsApp messages and regular video calls, when the poor Internet connection allows it. “We've been told very clearly that for a victim to be associated with the ICC is a source of danger,” said von Wistinghausen. Victims’ safety is an issue, as well as the safety of the legal representatives prevented from visiting their clients in Sudan.

“Thrown back to former times”

But violence in Darfur has never really ceased since 2003. Back then, hostilities first began as local non-Arab rebel groups, including members of the Fur community, attacked government targets, accusing the Sudanese leadership of oppressing Black African groups. Al-Bashir sent the Sudanese military forces and the Janjaweed, an Arab militia group, to counter the insurgency, and the civilian population was not spared in the attacks. The United Nations estimates that some 300,000 people have died and 2.7 million have been displaced.

The common legal representative of victims in this ICC case had a chance to speak to a limited number of them but they said that they felt “the same feelings of fear and insecurity”. “I think that many of the victims feel like they are thrown back to former times” says von Wistinghausen, adding that they are losing hope, for justice and to return home.

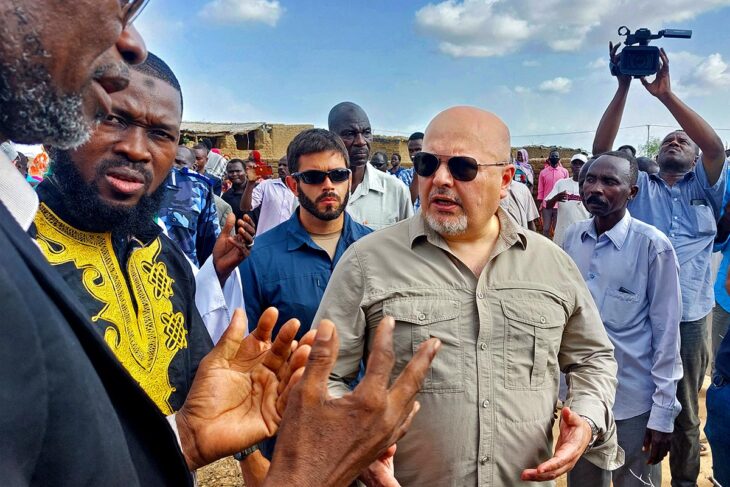

“Almost two decades after, what happened to them is being recognized on this forum,” noted Shah Anand, associate counsel in the case. “It is certainly significant for them and for the larger community that this case is moving forward. But they are having to deal with the consequences of what happened to them two decades ago, which are continuing today.”

A TRIAL IN THE MIDDLE OF THE ROAD

56 witnesses have already appeared before the International Criminal Court (ICC) Trial Chamber during the prosecution’s phase, which closed last February. According to the Prosecutor, Ali Muhammad Ali Abd-Al-Rahman alias Ali Kushayb had knowledge about the conflict and was willing to implement the state policies. He cooperated with senior Sudanese government officials, including Minister of State for the Interior, Ahmad Muhammad Harun, from whom he allegedly received arms and money to distribute to the Janjaweed militia.

The prosecution stressed the widespread and systematic nature of crimes committed against civilians of the Fur communities in Wadi Salih and Mukjar, localities of West Darfur. The list of alleged crimes includes intentional attacks on a civilian population, murder and attempted murder, looting, destruction of property and livestock, inhumane acts, outrages upon personal dignity, rape, torture, forced transfer of population, and cruel treatment.

After the legal representatives for the victims, it will be the defence turn to present its case. This is scheduled to start on August 28 before the Trial Chamber.