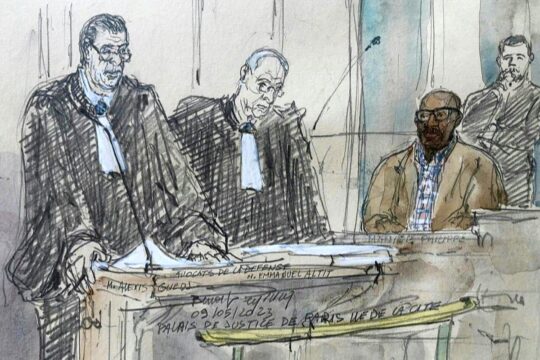

Thirty-one days of hearings, 106 witnesses and civil parties heard, 288 hours of debate: on trial in Paris since May 10 for genocide, crimes against humanity, complicity in crimes against humanity and conspiracy to participate in these crimes, Philippe Hategekimana was on June 28 found guilty on almost all charges.

The former Rwandan gendarme – who obtained French citizenship in 2005 under the name Philippe Manier - was accused of multiple murders and massacres committed on the territory of the Nyanza gendarmerie, where he was chief warrant officer, in the southern Rwandan province of Butare.

The accused pleaded his innocence to the bitter end, insisting that at the time of the massacres he had left the region and that he helped several Tutsi families to escape. "The genocide did take place, I witnessed it. But I have nothing to reproach myself for," he declared on June 20. At the start of his trial, Hategekimana talked about his life before and after the genocide, but throughout the hearings he refused to comment on the events of which he is accused, stating only that he was not present.

"What do we know about Philippe Hategekimana?" asked public prosecutor Céline Viguier on June 26. "No comment" was probably the phrase he uttered the most, along with "I don't know this witness". Recalling that no member of the accused's family came to testify, she continued: "The feeling we get is that Mr Philippe Manier doesn't want us to know too much about him, so that we stick to the version of himself he's willing to give.” And it was this version that the two prosecutors set out to dismantle, piece by piece, in a presentation lasting almost five hours, at the end of which they requested a life sentence.

The contradictions of “Biguma”

Starting with the question of his presence in the Nyanza region from April 23 to May 1994 during the bloody days of the massacre, Hategekimana asserted that he was either leaving or had left, transferred to Kigali. "Should we believe him?" asked Céline Viguier. "His statements have varied so much, depending on the person questioning him.” The former gendarme, she recalled, over time gave different departure dates, declaring himself unsure of the precise day -- "It was so long ago," he told the examining magistrate -- while several "corroborating testimonies" placed this departure "in mid-May" at the earliest, the prosecutor stressed. Hategekimana "has a peculiar relationship with the truth", she asserted, saying he invented a past for himself when he applied for asylum, but also in the resumé he produced as part of his job search. He also changed his name several times. As for the nickname "Biguma", by which victims and witnesses referred to him throughout the proceedings, the accused only denied it in the final days of the trial, during his final interrogation, added her colleague Louisa Ait Hamou. "Philippe Hategekimana is 'Biguma'," she said, "and that's how we'll refer to him.”

The public prosecutor set out to demonstrate inconsistencies in the accused's account. She pointed to the fact that he could remember few colleagues’ names although he claimed to have been head of human resources at the Nyanza gendarmerie, said he had not heard of Nyabubare hill despite it being in the area, nor the burgomaster Narcisse Nyagasaza, whom he was accused of killing. “How could he not know him?" Louisa Ait Hamou exclaimed. "Even under normal circumstances, the gendarmes had to deal with the civil authorities in their sector. And Narcisse Nyagasaza was one of the few elected Tutsis in the region.”

Lies or inaccuracies?

Unlike that of the accused, the accounts of witnesses such as Israël Dusingizimana have not varied, the prosecutor noted. Dusingizimana, convicted of genocide in Rwanda, recounted the coordination between Interahamwe militia and the accused with his gendarmes during the massacre on Nyabubare hill. "There are so many concordant accounts," asserted Céline Viguier, taking the example of two witnesses "who know absolutely nothing about each other" but described the same scene where the chief warrant officer shot a woman in labour on Nyamure hill. “While crimes against humanity and genocide can now be documented in real time, this was not the case at the time of the events," she argued. “What we have left are the accounts of the victims, the survivors. And these survivors are few, because so many Tutsis were massacred. Nobody was supposed to be left to tell what happened in Rwanda at that time.”

These stories are "rare and precious," she stressed. “We're not saying that all accounts must be taken seriously, but we must differentiate between lies and inaccuracies. Every testimony must be assessed in light of the passage of time. Can we blame a person who has lost his whole family for not remembering the exact day and time, where they were, the make or colour of a car?”

“Hategekimana's only response to these victims was a flagrant lack of empathy," asserted Viguier. She noted that the accused, in his last statement, "said he sincerely sympathized with the suffering of the victims -- but he called them liars". On the contrary, during his psychological examinations, "Mr. Manier talked about his own suffering, his own losses", particularly during the Rwandan Patriotic Front (armed opposition that seized power in Rwanda in July 1994) attack on a camp where he had taken refuge in the Democratic Republic of Congo. “No one disputes the RPF's crimes, but no one can call them genocide, and they in no way erase what happened before," the prosecutor said. “But these crimes allow the genocidaires to turn the narrative on its head. Instead of perpetrators, they become victims. And that's exactly Mr. Manier’s narrative."

"We have a defendant who disputes all the charges, who on the contrary presents himself as a victim, who expresses no empathy, who doesn't hesitate to lie, and who has never allowed the court to know who he really is," she added. “Yet, far from being a mere executor, Hategekimana instigated genocide in the Nyanza region. France cannot be a safe haven for genocidaires."

"We have a real credibility problem"

“France cannot take responsibility for an unfair conviction,” the defence retorted. On June 27, in a four-part plea, Hategekimana's lawyers asked the court for an acquittal on all charges. And the defence countered the prosecution’s arguments about contradictions and gaps in the testimony given over the past two months.

Attorney Margarita Duque spent over 40 minutes unravelling the many testimonies about crimes committed at roadblocks across the region - "hearsay evidence" – while her colleague Fabio Lhote tackled those about the Nyamure Hill massacre. “Let's do a little arithmetic," he suggested. “Of the 18 people interviewed, four have never heard of Biguma, ten are repeating what they were told, and the four remaining testimonies are questionable because confused, misleading and given by people convicted of genocide. On the events at Isar Songa, it's even more blatant: 12 people were interviewed, nine of whom had never heard of Biguma, and not one eyewitness could attest to Philippe Hategekimana's presence there!"

Many witnesses varied their accounts from what they told investigators to what they said in court hearings, he asserted, claiming to have seen the accused at the scene of the events or heard someone say Biguma had arrived, and then saying they learned after the event that Biguma was involved. "We have a real credibility problem. Did you see him or not see him? Hear him, not hear him? People are not consistent," said the lawyer with a flourish of his arm. “It gives you an idea of the power of rumour, and that's what this case is all about."

Unlike other witnesses, the numerous civil parties in this case do not take an oath to tell "the whole truth", the lawyer said. "The word of the accused is as good as theirs, we must remember.”

No genocide denial

Yet this word has been denied time and again, Duque protested, with the accused presented in such a way that every one of his actions is open to question. "Mr. Manier decided to exercise his right to silence; the civil parties considered this a confession. How can exercising a right be considered a confession?” She said the victims may have touched her "personally", but that "we must also understand that the majority of them did not know Mr. Manier, they simply heard that all they had to do was come and testify here to get some answers". As for the genocide denial accusations she believes have been levelled at the defence during this trial, she brushed them aside: "Mr. Manier himself does not deny the genocide. And to use his words: acknowledging one's innocence is not the same as denying the suffering of the victims."

Testimonies are indeed the "backbone" of this case, stressed lawyer Alexis Guedj. And when a case is based "solely on testimonial evidence, the least that can be done is ensure that these testimonies are unassailable". On the Nyabubare Hill massacre, "we heard from around 20 witnesses, and all to arrive at what conclusion? What is certain, what is intangible, what is truly in the realm of evidence, perfect proof that we can believe, whether we are lawyers on not?"

Attacking the evidence of convicts

But the defence particularly attacked the word of former genocidaires from the Nyanza region, convicted in Rwanda and appearing in custody. Their words were highly incriminating for the accused, placing him at the heart of the events. “Mr. Philippe Hategekimana is presumed innocent," recalled Guedj, "and his word is weighed against that of people convicted of horrific crimes, which is given more credit? And you, the jurors, ask is that the justice I must render?”

"Is it possible to judge without asking the question of false witnesses and detainees?” lawyer Emmanuel Altit continued. “Anyone who has followed the Rwanda trials knows that the credibility of imprisoned witnesses is an issue. How could it be otherwise in a country that is not governed by the rule of law?”

The previous day, the women prosecutors spent almost half an hour castigating the defence suggestion of a plot by Kigali. "As soon as witnesses directly implicate the accused, the defence deems them liars and manipulators. Many of them were attackers, and we have to call them what they were: murderers. But what's in it for them to testify?" said Céline Viguier. The public prosecutor pointed out that, under Rwandan justice, convicts who have admitted the facts and asked victims for forgiveness have benefited from remissions of sentence. But those who have not pleaded guilty have never obtained anything, and "certainly not" in exchange for testimony. And besides, "why would Rwanda go out of its way to convict an innocent gendarme, a 'little fish' to quote his wife?" asked the prosecutor.

"It's simple: because he's here, exposed because of the denunciation against him," replied Altit. "The Rwandan regime is dictatorial. Such a regime needs legitimacy, and what better legitimacy than to stand up for the victims of genocide? In addition, it makes possible to point the finger at France, accused of having supported the genocidaires." For this lawyer, Hategekimana is nothing less than a "scapegoat", caught up in a "political balance of power that is beyond him".

Doubt thrown out

“Yet, you don't even need to enter this debate,” he told the jurors. “The burden of proof is on the prosecution. The defence doesn't have to prove anything. The defence has to show the weaknesses, the gaping holes in the case. It must point out the doubts, and there is an ocean of doubts.” Guedj said the main problem was the evidence. "You’re being pushed to convict on the basis of a case built on sand,” he argued. “Does France have such a strong guilt complex because it let this genocide happen? And is the Court of Assizes being asked to shoulder this responsibility? There's nothing worse than convicting a man on hearsay, on gossip.” And, rereading the jury oath, he recalled like his colleagues that "doubt must benefit the accused".

After a long deliberation, the court decided that there was no doubt.