In the garrison cemetery on Columbiadamm in Berlin's Neukölln district, there is a four-foot-tall stone which commemorates seven German soldiers who volunteered for the “campaign in South West Africa” between January 1904 and March 1907 and “died a hero’s death”. In other words: this monument does not commemorate victims, but perpetrators of genocide.

The stone, popularly known as the “Herero Stone”, dates from 1907 and refers to a short but important period within the German colonial rule of what is now Namibia (1884-1915). German colonial policy was characterized by land and cattle theft, racism, mistreatment and exploitation. Resistance of indigenous Herero and Nama was ruthlessly crushed.

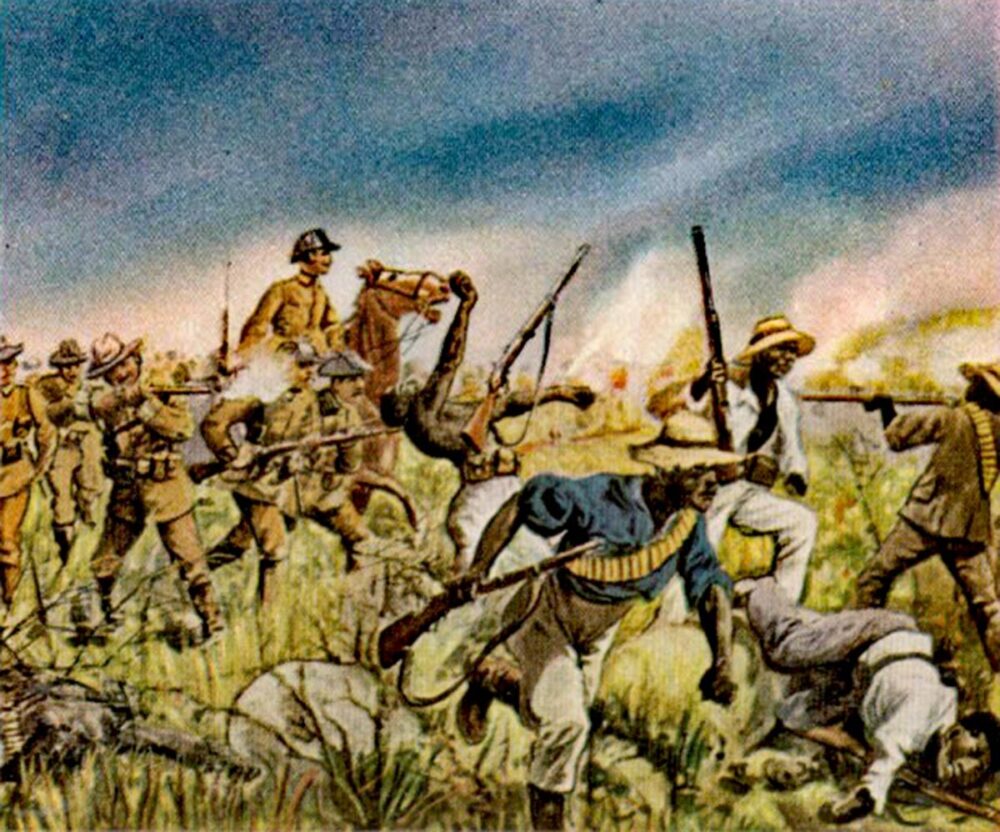

In 1904, a surprise attack by Herero led to the October 2 "extermination order" from German Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha. German soldiers drove Herero into the desert where many died of thirst, hunger and exhaustion. From 1905, Herero and their Nama allies were imprisoned in concentration camps where they worked as slave laborers on railways or became victims of medical experiments. This genocide ultimately killed 50,000-65,000 of the 80,000-100,000 Herero and 10,000 of the 20,000 Nama.

Conflicting views on the German colonial past

In light of this history, it is not surprising that the monument is not widely loved. Anyone who currently takes a walk in the cemetery will see, for example, that the stone has been daubed with the text: “No racist commemoration for Nazis and genocides”.

The stained stone clearly shows the conflicting views on the German colonial past. On the one hand there is criticism expressed by the graffiti, namely that it is racist myopia to commemorate perpetrators of a colonial genocide. On the other hand, there is still a colonial approach to national history, which is mainly expressed here in silence and indifference. In 2023, there is not even a sign at the monument that explains German colonial rule or refers to the fact that the “campaign in South-West Africa” is a colonial euphemism for genocide. Moreover, the stone only focuses on Germany's own suffering and there is no other monument in the city that commemorates the genocide. These omissions make the monument seem like an innocent memorial to seven lives. The loss of the colony in 1915 during World War I clearly does not mean a loss of a colonial bias.

The five-month-old graffiti on the stone, on the other hand, could be seen as a cry from society for postcolonial modernization. Such criticism may not be surprising today, but as is often the case with postcolonial criticism, it has a long history. In this case, there is a long chain of critical reactions to the monument.

Beating around the bush

Ever since 1973, when the stone was moved from a barracks site to the cemetery, there were voices that the monument was offensive and inappropriate. But it was not until 2004 that local politicians felt compelled to do something with this criticism. An important reason for their sudden interest was a temporarymemorial plaque placed by various interest groups, in honor of the 100th anniversary of the genocide. This provisional plaque stated: “In memory of the victims of the German genocide in Namibia 1904-1908.” Although the plaque “disappeared” after only a few days, the local administration of Neukölln was now prepared more than ever to face the colonial genocide: in the same year the district assembly passed a motion submitted by the Social Democratic Party to erect a permanent memorial plaque for the victims of the genocide.

But anyone who thinks that this changed vision regarding the German colonial past was going to be processed quickly, is wrong. It was only after five years of deliberation that a permanent plaque was placed at the monument. On a black placard placed at the foot of the stone in 2009 we can read in white-engraved letters: “In memory of the victims of the German colonial rule in Namibia 1884-1915 and in particular of the colonial war of 1904-1907.” The term genocide, the mention of the Herero and Nama and that of casualty numbers remain absent. As such, the text disguises more than it reveals.

The reason that this text beats around the bush has probably been money. If you look closely at the black placard, you will see that something has been written there and has been removed. The same activists who defaced the stone last April wrote that “Berlin's District Assembly and Neukölln District Office did not want to write ‘genocide’ here because that could justify reparations.”

This is a fair comment. In 2009, the Federal government had not yet recognized the genocide. What happened a century ago was not supposed to be a genocide but a “colonial war” – to evade reparations.

And that’s why up to now the monument continues to tell a rather one-sided, colonial and outdated official story, and from time-to-time unofficial postcolonial updates become visible in the form of red paint and postcolonial slogans.

The times they are a-changin’

The question now is how the defaced monument fits in with today’s German approach to the past. Historians recognize that for a long time little attention was paid to the colonial past in Germany. “Many people only have a vague idea that Germany was a colonial power,” says historian Jürgen Zimmerer. Only with publications by him (for example Von Windhuk nach Auschwitz?, 2011), or by Sebastian Conrad (Globalisierung und Nation im Deutschen Kaiserreich, 2006) did the colonial past receive more attention.

According to historians such as Dirk Moses, we should see this long period of relative silence surrounding German colonial history as an unpleasant consequence of the great focus on the Holocaust and its uniqueness. The Shoah occupies such a dominant position in German remembrance culture that it stands in the way of commemoration of colonial crimes.

But something is definitely changing. For example, this year, a feature film “Measures of Men” was released. The film, directed by Lars Kraume, highlights Germany’s brutal colonial past in what was then German South West Africa. Moreover, since the turn of the millennium, the subject has been increasingly included in German textbooks.

However, textbook inclusion of the colonial genocide does not necessarily mean a conscientious dealing with this past. For example, the 2003 textbook Horizonte II: Geschichte für die Oberstufe asked students to “contrast the positive and negative aspects of imperialism.” Instead of reflecting on the German colonial project, the textbook still attempted to defuse criticism of the colonial project. In more modern textbooks, we see no such mitigation of colonialism. But here too, the intrinsically racist and oppressive nature of the entire colonial occupation is often (partly) ignored or distorted. The focus is mainly on German colonial experiences and perspectives, overlooking those of Herero and Nama. Colonialism thus becomes primarily a matter of suppressing a rebellion by Herero, resulting in an unfortunate genocide.

Genocide recognition in 2021

The temporary exhibition “Schaumagazin Afrika” in the prestigious Humboldt Forum in Berlin is doing a better job. The exhibition shows photos from the colonial period, interviews and reflections on German textbooks. By focusing on experiences of Namibians and people with a German-Namibian identity, the exhibition manages to break through the rigid national framework. It shows how the original population was continuously framed as inferior and how this view can still have an effect today. As such, the exhibition accounts for the root of current worldviews of different groups of people in German society.

The district administration of Neukölln also seems to be aware of the need for a different representation and commemoration of colonialism and the genocide. Thirteen years after the black placard was placed at the cemetery, the local government announced in 2022 that it strives for a redesign of the monument.

Is the time finally ripe for a monument that does justice to this history? The recognition of the genocide by Angela Merkel's government in May 2021 is positive.

Talking about reparations

The press release from the Neukölln museum, which is organizing an exhibition on the memory of the genocide in November 2023, also gives hope. The focus on memory suggests that the exhibition will reflect on the different ways in which the genocide has been portrayed and politicized over time.

But let's not celebrate too soon. It still appears to be easy to ignore the experiences and voices of formerly colonized groups. The exclusion of Herero and Nama representatives from talks about reparations for German colonial crimes makes that painfully clear. Without involving these groups, the Federal government and the Namibian government agreed in 2021 that Germany would pay 1.1 billion euros to Namibian development projects. Descendants of the genocide victims prefer that the reparations go directly to them. Not only do they fear embezzlement of the money, they also want to be able to tackle the poverty and marginalization as a result of the genocide. They therefore demand that Namibia renegotiate the reparations and ask for a place at the negotiating table. The fact that the voices of Herero and Nama are not central to these conversations shows how colonial ideas still find their way into the present.

Whether the difficulties surrounding the reparations will also influence the redesign of the Neukölln monument remains to be seen. Despite the increased willingness to adopt a postcolonial approach, the colonial paradigm in which we view the past has proved to be quite dominant. This Fall we will find out exactly how dominant this one-sided and often concealing narrative still is. Let's hope that a changing German society has managed to create space for the postcolonial voices that have been sounding for so long. Because only when the Neukölln memorial recognizes the victims of the Herero and Nama genocide can we say that there is no more “racist memorial for Nazis and genocides”.

Anne van Mourik is a PhD candidate at the Niod Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies and the University of Amsterdam. Until 2020 she worked as a researcher in the ‘Independence, Decolonization, Violence and War in Indonesia 1945-50’ program. Together with Peter Romijn, Remco Raben and Maarten van der Bent she worked on the research project about the ways politicians and colonial administrators dealt with large-scale violence. Her current research explores victimhood/perpetrator discourses with regard to German hunger during and after both world wars.