“When the news came that my husband became captive, I didn't understand what was going on,” recalled Anna Mykhailyshyna, a regional representative of the Association of Families Poligon 56 Berdiansk, in western Ukraine. She was speaking in June in The Hague at a panel event organised by the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), an intergovernmental organization based in the Netherlands. Created after the former Yugoslavia war at the initiative of US President Bill Clinton, ICMP is now assisting the Ukrainian government and its forensic teams on DNA identification of missing persons.

Mykhailyshyna’s husband had enrolled to defend Ukraine after the Russian army stormed into the country in the late February 2022. He was captured over a year ago and his whereabouts are uncertain. “My husband was not a military man and we didn't know what to do. We monitored 24/7 Telegram channels, Google and Internet,” Mykhailyshyna says. Then she started coordinating with other families of missing soldiers of the same brigade, in order to try and find legal, psychological and medical support together. “My daughter is seven years old and for three months we have been visiting a psychologist because every day she comes back from school with the same question: when will my father be back?”

Unified Register of Missing Persons

It was a year later, in May 2023, that Ukraine’s Ministry of Interior launched the long-awaited Unified Register of Missing Persons that includes civilians and soldiers. In June, it already counted 24,000 cases, said Oleg Kotenko, the Commissioner for Persons Missing in Special Circumstances. The Commission itself was created in May 2022 and reported to the Ministry of Reintegration.

But as the war in Ukraine continues to wage, the number of missing people keeps rising, and the government is striving to coordinate data corresponding to a wide variety of situations. For the month of July only, the National Information Bureau for Prisoners of War, Forcibly Deported and Missing Persons, which was established in March 2022, said it received 15,500 “appeals”, and in August 17,000 more from relatives asking for information on prisoners of war, missing persons, and people deported or forcibly displaced.

Anatolii Solovei, a ministerial advisor to the Embassy of Ukraine in the Netherlands, told Justice Info that according to official figures 19,556 Ukrainian children have been deported to Russia. Speaking at a ICMP book presentation on September 14, he said that so far only 386 could be brought back. To him, both this figure and the one of missing adults are probably an underestimate, since Ukrainian authorities have no access to the Russian-occupied territories and Russia is not answering their requests for information.

Children killed or deported to Russia

Some are “likely dead and are in the occupied territory, where there is no possibility to safely retrieve the body and bury it”, explained Olena Bieliachkova, coordinator of families of prisoners of war groups for a Ukrainian NGO, Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR). Some were killed in an air strike or missile attack that left no body or remains of the persons, she said. And children can go missing after they were killed or deported to Russia – acts for which the International Criminal Court last March indicted Russia’s president Vladimir Putin and its Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova.

“The Russians have also captured and killed civilians with an active pro-Ukrainian opinion, because they had Ukrainian symbols on their clothes or in their homes, or because of patriotic tattoos,” Bieliachkova continued. As reported by Associated Press, thousands of civilians are held in prisons in Russia or in the occupied territories of Ukraine, where they live in appalling conditions and are used for slave labour by Russia’s military, in violation of Geneva Convention principles.

Most of the abducted civilians are Ukrainian volunteers, activists, public figures, and academics who refused to cooperate with the occupying authorities, as well as relatives and friends of Armed Forces of Ukraine members, Ksenia Onyshchenko, a lawyer with the Ukrainian human rights group SICH, told Justice Info in a written interview. “Open resources show many videos of the occupation authorities conducting the procedure of expulsion of civilians,” Onyshchenko continued. But they never reach Ukraine, she said.

“In most cases, abducted and killed civilians are listed as missing, as neither their families nor the competent authorities can obtain reliable information,” said Bieliachkova.

Figures on the missing soldiers remain vague and unconfirmed, but the picture that emerges is dramatic. US officials recently quoted by the New York Times said that the number of Ukrainian dead soldiers since the beginning of Russia’s full invasion in February 2022 could amount to 70,000, out of 200,000 Ukrainian casualties. Many of them remain unidentified, and Kyiv is keeping official records classified, leaving the number of missing soldiers unknown.

“DNA lost by our authorities”

Associations of victims’ families complain that DNA processing is too slow and that they still lack a clear door to knock on for effective legal and psychological support. There are several reasons why a large number of bodies are still unidentified, said Onyshchenko. Families have not submitted their DNA samples, or have fled abroad before they could do so.

But part of the delays lies with the institutions. “Conducting an independent DNA examination and adding the samples to the unified register of missing persons will significantly accelerate the identification process,” said Onyshchenko. “I have repeatedly heard from the families of the missing that the DNA samples taken by our authorities are lost, and families have to submit them multiple times,” said Bieliachkova. According to her, samples are “processed poorly and over a long period of time, up to five or seven months”. By that time, she added, some of the bodies are buried without identification.

The wait is reportedly similar for deceased soldiers whose bodies were brought back as part of exchange procedures between Ukraine and Russia. Bieliachkova told Justice Info about the case of the July 2022 Russian attack on a building housing Ukrainian prisoners of war near Olenivka, in the region of Donetsk, which according to Ukrainian investigations killed at least 50 servicemen. Although their bodies were brought back in 2022, only 33 of them were identified in July 2023, while the examinations on the other 24 bodies continue.

The ICMP offered to assist Ukrainian authorities in collecting and processing DNA on a large-scale and making sure the evidence is admissible in future trials, explained Kathryne Bomberger, who has been the head of the organization for 25 years. And on August 31, ICMP signed a protocol with the National Police of Ukraine that will enable its investigative department to use ICMP technologies to locate and identify the missing. The ICMP aims to run high-level testing in their laboratories and store all evidence into one secure database.

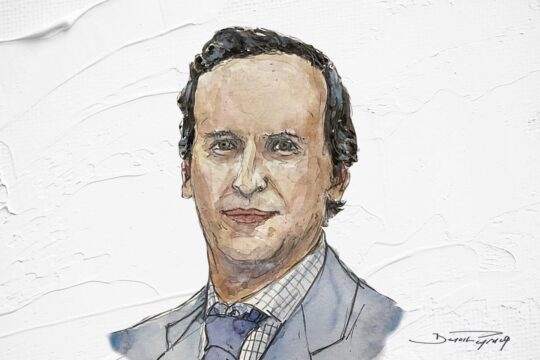

“The Justice Ministry will work with the families and civil society as well as with ICMP” in the process of finding the missing, said Ukraine’s Minister of Justice, Denys Maliuska, in a pre-recorded video broadcast in June in The Hague. The signed protocol allows the ICMP to start collecting DNA data from Ukrainian families living outside Ukraine in Europe. But the government hasn’t yet signed the agreement that would allow the organisation to collect and process DNA samples, Bomberger said, although this cooperation agreement “would help close the case for families, help provide compensation to them, and could also be used as evidence in court.”

“The cooperation between ICMP and the Ukrainian government is crucially important,” stressed Solovei from the Ukrainian embassy in the Netherlands. He told Justice Info that the agreements ICMP is signing with Ukrainian institutions, like the one with the National Police finalised in August, are in his opinion “flexible and swift instruments”. To him, these protocols are preferable to a big umbrella agreement as they “start working from the very moment of signing” and do not need to be ratified by Parliament.

In response to our question on whether Kyiv might not be signing a full cooperation agreement because it wants to keep its casualties classified, Bomberger stated: “We can find ways to deal with a necessity of confidentiality but at the same time respect the rule of law and the rights of families of the missing to truth, justice, and reparations.”

A single door for families

The official procedure when someone goes missing starts with relatives filing a statement to police and the opening of criminal proceedings, explained Onyshchenko. This applies to civilians, while families of missing servicemen are informed by the regional enlistment centres and social support offices that receive information from the military units. The next step for families is to get a certificate from the Unified Register of Missing Persons and apply for the rights to get support from the government. In the case of civilians, this mainly consists of benefits for close relatives, while the families of missing soldiers are also entitled to financial support and free or discounted social services, like public transport and healthcare.

Families can also appeal before a tribunal if they find their rights are not respected, said Bieliachkova. On paper, families of missing soldiers can get legal and social support from the government. But information on this is lacking, and Onyshchenko said relatives are often unable to get proper help and have to turn to organisations like SICH. “Unfortunately, today in Ukraine there is still no effective social and psychological support for families of missing persons, and they find themselves facing their grief alone. When a mother or a wife of a missing person comes to us, the first thing we see is a frustrated person who desperately wants to find her loved one,” she says. Some put themselves in physical danger by going to the Russian-occupied territories or sharing their data online and becoming victims of frauds, said Onyshchenko.

These last months, the government of Ukraine seems to be doing more to find solutions to a tragic issue that is affecting more and more families in Ukraine. Two months ago, the Commission on Missing Persons opened a new hotline with specialists in legal support for them. At the end of August, according to the ministry’s website, more than a thousand citizens had already called the hotline for help. And in September, around the same time the Ukrainian Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets announced the creation of a new mechanism to return deported children, Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk held a meeting on a possible mechanism for the search and return of civilian hostages. “We have to return everyone. Both prisoners of war and children, and civilians,” said Vereshchuk in a public statement.