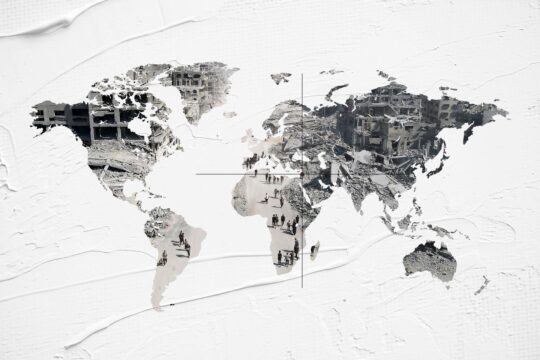

Against the backdrop of horrendous images from Israeli towns attacked by Palestinian military organisation Hamas and the declaration of war by Israel on residents of the Gaza Strip, the slow-moving investigation by the International Criminal Court (ICC) into alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity in the occupied Palestinian territories has hardly been mentioned.

By contrast with the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 when multiple countries referred the matter immediately to the ICC office of the prosecutor, no states have called on the ICC prosecutor to now step up his work on Palestine and provide accountability for alleged crimes.

When the Palestinian Authority lobbied to become a member of the court after Israeli incursions in 2008 and 2009, it became part of a multi-pronged strategy of lawfare and state-building. The aim was to pressure Israel in international fora, provide an alternative mechanism to the bogged down peace process, assert Palestinian sovereignty and potentially provide redress for some of the victims of Israeli occupation and brutal military interventions in Palestinian territories of West Bank and Gaza.

Since that time, the ICC’s engagement with repeated violations of international human rights in the occupied Palestinian territories has limped along, culminating in an investigation apparently on the back burner, showing no concrete results.

A chorus of voices continues to contrast the international community’s emphasis on accountability for international crimes committed in Ukraine with those of Palestine. The rumblings of critics have become louder after the indictment of Vladimir Putin. They essentially asked: Why such mobilisation and unusual capacity to complete an investigation when it targets a political adversary of Western powerful states and main contributors to the ICC, and such a lack of courage and resources on the situation in Palestine? Now the prosecutor faces multiple calls from the NGO and human rights communities for his office’s full engagement.

Prosecutors passing the buck

It was the ICC’s second prosecutor Fatou Bensouda (2012-2021) who declared in 2019 that “war crimes have been or are being committed in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip”. The court officially opened the investigation into the situation in Palestine in 2021.

Her predecessor Luis Moreno Ocampo had explained his hands were tied until Palestine became a recognized state at the UN. But after the state of Palestine became a full member of the court in 2015, its officials began to submit reams of evidence. Bensouda added the situation to her preliminary examinations. She continued to warn all parties after opening her investigation into Palestine, while admitting that the situation was "politically fraught" and surrounded by “rhetoric” and “misinformation”. During every flare up and incursion since the ICC became involved, war crimes have been alleged and calls for the court to investigate have been consistent. But Bensouda had also kicked her own investigation into the long grass by asking ICC judges to first rule on the precise parameters of the court’s authority. The judges’ February 2021 ruling confirmed jurisdiction over the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem since June 2014. It came as the court’s third prosecutor Karim Khan was preparing to take office.

Khan established the first prosecution team to start assessing the evidence. But with no public pronouncements, no details of which specific crimes the court might address, observers have become increasingly critical of the ICC investigation.

The unknown scope of investigations

There were many instances of alleged serious crimes since 2014, and the current war in Gaza involves thousands of victims and individual incidents. But the Office of the Prosecutor refuses to be drawn on what it may investigate. “I can't tell you what our lines of inquiry are in any of our situations. It's not just about Palestine. We don't really share openly what we're looking at for good reason. Not only do we not want to take away the security and the protection that we provide for witnesses in particular areas, but we certainly don't want to tip anyone off as to what we're looking at a particular time. I can say that the court has very clearly said that the ICC has jurisdiction over the West Bank. But as to the lines in the inquiry, I'm sorry we never share those in relation to any of our situations,” Deputy Prosecutor Nazhat Khan (no relation to Karim Khan) told Justice Info in August.

Some elements, however, can be discerned based on previous statements by the Prosecutor’s Office. To support Bensouda’s request on geographical determination to the judges, her Office outlined the range of crimes it would investigate during the Israeli operation against Gaza in 2014. “On the basis of the available information, there is a reasonable basis to believe that war crimes were committed in the context of the 2014 hostilities in Gaza,” it said. The Prosecution was careful to point to both Israeli and Hamas alleged crimes stating that there “is a reasonable basis to believe that members of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) committed the war crimes of intentionally launching disproportionate attacks” and that “there is a reasonable basis to believe that members of Hamas and Palestinian armed groups committed the war crimes”.

In the current conflict alleged war crimes committed by all sides would be likely to come into focus, including actions by Hamas fighters in killing civilians and taking civilian hostages, and indiscriminate bombing by Israeli forces or, potentially, the cutting of power and food supplies to the Gaza Strip. Although there will be multiple challenges, including finding specific evidence to clearly prove which individuals and especially which individual commanders can be held to account, as the ICC is usually called to focus on the most responsible.

The challenge of admissibility

Recent developments in trials in European countries of former Syrian fighters have shown how social media evidence can be used to build cases of war crimes and crimes against humanity, beyond membership of organisations defined as terrorist.

Another major challenge to ICC investigations is the assessment of whether there are local efforts to sanction individuals and hold them to account for their actions, since the Court can theoretically only claim jurisdiction when domestic justice systems didn’t or couldn’t act. In 2019 the Office of the Prosecutor assessed that in the case of Hamas “potential cases concerning crimes allegedly committed by members of Hamas and PAGs [Palestinian armed groups] would currently be admissible”, but for the IDF, monitoring of proceedings before Israeli courts would be needed. “The Office notes that due to limited accessible information in relation to proceedings that have been undertaken and the existence of pending proceedings in relation to other allegations, the Office’s admissibility assessment in terms of the scope and genuineness of relevant domestic proceedings remains ongoing,” wrote the ICC Prosecutor.

Yuval Shany, professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, points out that the military authorities have “been much more transparent in actually putting out their information concerning legal proceedings, investigations” and “the military attorney general has published update reports about investigations”. But the long-term political backdrop in Israel is of challenges to judicial independence which would potentially affect an ICC assessment of the genuine nature of accountability for IDF commanders.

One of the most documented situations in history

In addition, Bensouda’s office had concluded to “a reasonable basis to believe that in the context of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, members of the Israeli authorities have committed war crimes” such as “the transfer of Israeli civilians into the West Bank since 13 June 2014.”

This is the context, human rights campaigners argue, for the systematic violence and the killings - the Israeli occupation and the building of settlements in the West Bank. “The situation in Palestine in general, especially settlements, is perhaps one of the most documented in modern history,” says Ahmed Abofoul from Palestinian human rights organisation Al-Haq. “The admissibility test is already determined and there is no need to collect hard evidence. It can be proven without having access to the territory”, he continues. “Satellite imagery can show the grand lines and where Israel transfers its population”.

The current actions have been preceded by increasing bouts of violence especially in the West Bank. Omar Shakir from Human Rights Watch, an American NGO, describes “unprecedented” numbers with a “spike in killings of Palestinians in the West Bank”, when looking back over the last 18 months. He points out that “2022 saw more killings of Palestinians in the West Bank than in any year since the U.N. began systematically reporting data on fatalities.” Even before the Hamas actions and Israeli counter-attack, 2023 was “on pace to exceed that.”

Trying to explain delays

So why is the ICC taking so long? Abofoul suggests “that perhaps the Office of the Prosecutor is looking to do a mapping of all crimes and perhaps try to target some crimes that underline the different violations that are being committed” – which “might be an argument why it's taking long.” But, he says, “to be honest, it's not really convincing.”

From a practical perspective it is instructive to look at the ICC budget allocation to the Palestine investigation. It went up to nearly 1 million Euro a year under Karim Khan’s prosecutorship, which is at the lower end of allocated resources, especially for such a large and complex and continuing situation. There are requests for increased staffing, witness protection, some outreach and some activity by the court’s Trust Fund for Victims, but no indications of a significant increase in proposed budget documents. There’s no sense “that there will be development in the Palestine investigation,” says Abofoul.

The UN Human Rights Council’s special rapporteur on Palestine Francesca Albanese believes the investigation is “understaffed and under-resourced” and apparently “stuck”. She joined with fellow special rapporteurs earlier this year expressing their concern for the state of the investigation and calling for “more resources to be dedicated” to it. They also presented again what they described as “solid evidence of allegations of human rights violations that may have been committed intentionally and systematically”. Nazhat Khan, however, says that while her Office has received has “an enormous amount of information and of very, very committed and dedicated reports,” that “we live in the world of evidence.”

“We have received a response to our concerns,” Albanese told Justice Info, “but it is not a response that indicates or suggests availability for a dialogue”. She continued: “If I compare what's happening to the situation in Palestine at the ICC now with how it appeared with the previous prosecutors, I see that the communities, the groups who have made the submissions feel that loss. Not communicating, not gaining a sense of progress from the Office of the Prosecutor sends the message that the situation does not warrant attention. This is degrading for the victims who have no other recourse to justice and accountability, but it is also rewarding for the architect and executioner of all of this.”

Lack of access?

For his part Karim Khan has complained, while speaking at the British Institute of International and Comparative Law, about what he sees as the “complete disconnect between the reality and the polemics” in the critiques of his office’s approach to the investigation in Palestine. “When I inherited the office,” he says, “there wasn't even a team” for Palestine. “I've got to try to manage the resources we've got effectively, and Palestine and Israel have not been forgotten.”

One of the issues potentially making it more difficult for the court to act is lack of access. No representatives of the court have officially engaged on the ground with either Israeli or Palestinian authorities. Nazhat Khan says it is a priority for the office: “Discussions with local authorities, local judiciaries, members of the bar, NGOs and civil society are so valuable and I hope that the prosecutor is able to visit. We will leave no stone unturned to enable that process.”

Abofoul, however, argues that the ICC Prosecutor has access to all the evidence he needs. “Certain crimes in Palestine don't even need access to the territory. And that's why this excuse, if I can put it this way, becomes not really convincing.”