The year 2023 marked the 50th anniversary of Chile’s violent military coup, which ushered in 17 years of harsh dictatorship and cast a shadow over the hopes and dreams of utopian democratic socialists everywhere. The year also marks a quarter of a century since ‘Pinochet cases’ at home and abroad galvanised Chile’s previously dormant national courts, forcing them to either embrace justice, or side definitively with impunity for the former dictator and his henchmen. Perhaps suprisingly, they chose justice.

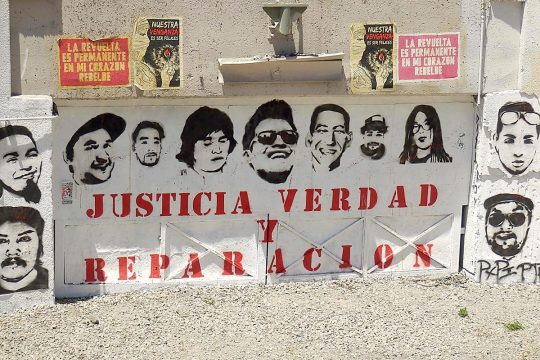

Two and a half decades on, Chile’s rather quiet, yet cumulative, experience of prosecuting atrocity crimes before domestic courts deserves more attention than it is often afforded. Imperfect, and above all slow, as subsequent justice has been, since 1998 Chile’s courts have resolved hundreds of cases of dictatorship-era killings, disappearances, and torture, and sent dozens of perpetrators to jail. They have also begun – more recently – to grapple with sexual violence, civil claim-making, spurious historical ‘convictions’ of political prisoners, and the duty to comply with Inter-American Court jurisprudence. In so doing, they demonstrate the perhaps unique potential of domestic justice systems as a transitional justice venue: Chile’s judges are today grappling not only with matters of innocence and guilt, but also with portentous decisions in the areas of truth, reparations, and guarantees of non-repetition.

As far as traditional criminal justice is concerned, as of July 2023, Chile’s Supreme Court had handed down verdicts in more than 530 cases for dictatorship-era crimes against humanity. Another 2,000 cases were still under investigation or awaiting resolution before lower courts. 234 former regime agents were in prison for their crimes, with dozens more – 57 this year alone – escaping justice only through the ‘biological impunity’ provided by death. Some of the investigations producing these developments stretch right back to January 1998 – when the first criminal complaints against former dictator Augusto Pinochet were brought by victims and relatives’ associations.

A record number of convictions in the past year

Pinochet’s arrest in the United Kingdom on October 16, 1998, on an international arrest warrant requested by Spain, turned this trickle of justice activity into a flood. Many cases have rumbled on ever since, but this year – no doubt with the approaching anniversary in mind – the Supreme Court has acted more decisively than before to shepherd investigations through the system at a less glacial pace. A record 67 Supreme Court criminal case verdicts have been handed down in the past 12 months. They include the largest single set of convictions ever ratified – 59 former secret police agents sentenced to jail terms at one go – and the culmination of some cases with a high international profile: in August 2023, seven former military officers were imprisoned for their part in the 1973 torture and murder of iconic folk singer Victor Jara. One of those responsible, now stripped of his acquired US citizenship, was arrested in Florida in early October as a prelude to deportation.

The road to justice has not been easy, with early obstacles including excessively lenient sentencing and a reluctance to allow cases involving survivors to go ahead. Defendants’ strategies have evolved from invoking amnesty, to flatly denying involvement, to delaying tactics that allow perpetrators to plead age-related infirmities or benefits. Today, however, the proportion of dead or disappeared victims for whom a case has been successfully concluded is at just over 34% and rising, while new cases are being generated all the time. Many are triggered by women survivors, determined to force greater acknowedgment of the sexual violence to which they were subjected as political prisoners. Judges, for their part, have learnt to disapply amnesty and statutes of limitation to crimes against humanity. They have digested the Rome Statute – the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court (ICC) – and other aspects of modern international criminal justice doctrine, and invoke these to supplement the deficiencies of the domestic criminal code. Specialised detective police and forensic personnel, designated to work these cases, have gone on to deploy their new skills in other areas of rights protection. The criminal responsibility of corporate actors, or at least of civilians, is beginning to be addressed through prosecution of businessowners who denounced union leaders, or doctors brought in by the secret police to oversee torture.

Turning courts into a venue for reparations

Today, however, the real novelty in the use of the courts lies in the diversification of the legal recourse being used. Civil, rather than criminal, justice is the fastest-growing area of activity, with hundreds of civil claims brought in recent times by relatives or survivors. Some are placed as part of a criminal investigation, others as standalone actions against the State. Over time, this use of civil law accrues advantages over the diminishing returns obtained from criminal prosecution of now-elderly individual perpetrators: it better points out the systemic, structural nature of the harms, foregrounding State responsibility.

Along the way, Chile’s courts have become perhaps uniquely progressive in declaring civil suits entirely compatible with receipt of administrative reparations – meaning relatives and survivors are eligible for both – and in waiving statutes of limitation and other legal obstacles for civil as well as criminal proceedings. This in effect turns to the courts into a venue for reparations: something that international criminal justice has always struggled to achieve (the ICC victims’ fund and etc. notwithstanding).

“De-Pinochetisation” in times of rising right-wing apologia

The courts have also become a place where the rights to truth and guarantees of non-repetition are exercised. A growing wave of denialism has been partly combated through Supreme Court injunctions. A recent one ordered a far right parlamentarian to retract and remove a slanderous social media video; others have obliged mainstream media outlets to publish front page retractions of official propaganda lies that they obediently gave voice to during the regime.

Survivors wanting to bring civil claims, or to have their kidnappers and torturers prosecuted, have also resorted to the courts to challenge secrecy provisions around truth commission archives. They won, first, the right to declassify their own case records, and then, the promise of legislation that will make the whole archive accessible to investigative magistrates. Via the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, survivors also won the right to have spurious long-ago convictions for ‘treason’ or ‘terror’ offences, imposed by military courts, finally dissolved and expunged from the record by the Supreme Court. One survivor, now a human rights lawyer, has brought repeated injunctions to ‘de-Pinochetise’ public space, forcing the removal of a statue to a Junta member and the expunging from military training facilities of homages to him, and to notorious secret police chief Manuel Contreras.

In a country beset, like many of its neighbours, by a rising tide of right-wing apologists for the authoritarian past, the courts are not a simple or sufficient answer to the challenges of changing hearts and minds. They are, however, performing a belated but hearteningly creditable role in producing and upholding judicial truths that underwrite the transitional justice agenda across its multiple dimensions.

Cath Collins is Professor of Transitional Justice at Ulster University, Northern Ireland and Director of the Transitional Justice Observatory of the Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago de Chile, where she was previously Associate Professor of Politics. The Observatorio maps current justice, truth and memory developments in Chile over the Pinochet-era dictatorship, and most recently has been supporting and monitoring the launch of the country’s first National Search Plan for the Disappeared. Prof. Collins’s recent academic publications include 'Pinochet's Accomplices: perpetration, complicity, and institutional culpability', with Francisco Bustos and Francisco Ugas, in Bird et.al. (2023) 'Perpetration and Complicity Under Nazism and Beyond', London: Bloomsbury; ‘An Innovative Response to Disappearances: Non-Judicial Search for the Disappeared in Asia and Latin America’. (2022, ed.) GIJTR/DPLF; and a background paper for the recent update of the UN Secretary-General’s Guidelines on Transitional Justice, launched October 2023.