A mother of three sons and a daughter, who used to live with her children and husband just outside Srebrenica, was relieved when she arrived in Potocari, where the United Nations compound was located, on July 11, 1995. By that time, her eldest son and husband had already set off through the forest along with other men in an attempt to reach Tuzla.

While in Potocari with her two other sons and her daughter, for two days she was trying to board one of the convoys and flee from Srebrenica that had been taken by the Army of the Republika Srpska (VRS). “After everything that I had seen, after having seen people being separated, I kept thanking God, because it seemed like we made it – me, my children and those friends of ours,” she recounted while testifying as protected witness.

But one soldier of the VRS singled out her son. “I begged him – why are you taking him away? He was born in 1981,” the witness recalled. She held him tightly, but the soldier grabbed him by his arm and dragged him to the left. Her son then turned around and asked her to keep his bag. “That was the last time I heard his voice,” the witness told the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) on July 26, 2000.

Krstic, the first conviction for genocide in Srebrenica

The ICTY judges quoted her testimony when rendering their first judgement for the Srebrenica genocide, against former Republika Srpska Army general Radislav Krstic. Krstic was the commander of the Second Romanija Motorized Brigade until September 1994. After that, he was the chief of staff of the Drina Corps of the VRS, and in June 1995 he was promoted major-general. In early November 1998, an indictment was filed against him, charging him with genocide, crimes against humanity, and violations of the laws and customs of war for his role in the events in and around the Srebrenica enclave between July 11, 1995 and November 1, 1995.

In 2004, he was sentenced to 35 years in prison for aiding and abetting the Srebrenica genocide. With this verdict, he became the first European to be convicted of genocide.

In the first instance verdict against Krstic, the ICTY chamber concluded that Bosnian Muslims were killed and suffered serious injuries because of their religious affiliation and the plan to ethnically cleanse the enclave. The judges called it a deliberate decision to kill the men, making it impossible for the Bosnian-Muslim population in Srebrenica to survive. “Stated otherwise, what was ethnic cleansing became genocide. The Trial Chamber is also convinced beyond any reasonable doubt that a crime of genocide was committed in Srebrenica,” it stated.

This and other judgements “represent the foundation of international criminal justice, and have played a key role in establishing the truth and responsibility for the most serious crimes committed during the conflicts of the 1990s in the former Yugoslavia, including the genocide in Srebrenica”, the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals, the successor to the ICTY, told Detektor. The work of ICTY and the Mechanism has been crucial to bringing high-ranking perpetrators to justice and establishing the fact that genocide took place in Srebrenica in July 1995, which has also been judicially confirmed by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the Mechanism stated.

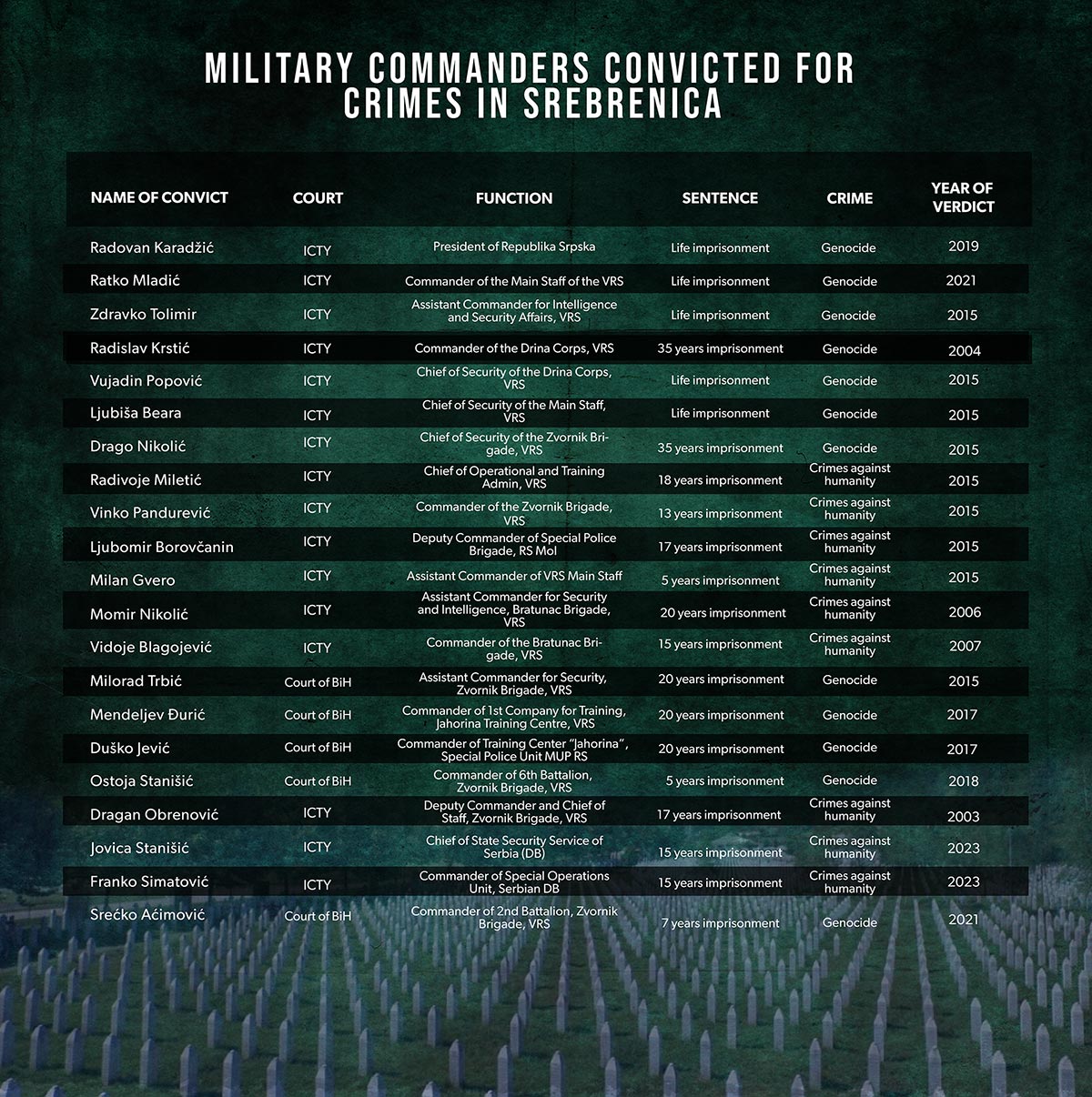

In addition to Krstic, seventeen more people were convicted in The Hague for genocide and other crimes committed in and around Srebrenica. Including Radovan Karadzic, Ratko Mladic, Zdravko Tolimir, Vujadin Popovic and Ljubisa Beara, who all were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Confessions or apologies for benefit

Krstic is still serving his sentence in Estonia and has been denied early release on several occasions. In his last request in 2024, Krstic acknowledged his responsibility. “I accept the tribunal’s verdicts from 2001 and 2004, where it was established that the forces of the army to which I belonged committed genocide against Bosniaks in Srebrenica in July 1995, that I aided and abetted the genocide by knowing that some members of the general staff intended to commit genocide,” Krstic wrote to the Mechanism.

Unlike Krstic, the request for early release of Vinko Pandurevic was granted. He expressed regret for having failed to do more to prevent the horrific events, conveying his apology to victims. The Hague court also approved the requests by Momir Nikolic, Drazen Erdemovic, and Dragan Obrenovic. They admitted guilt during their trials.

In May 2023, Nikolic concluded a plea agreement with the prosecution, agreeing to testify at other trials related to Srebrenica. He also testified at the Vidoje Blagojevic and Dragan Jokic trials, together with whom he was originally accused. “I sincerely want to express my deep and honest regret and remorse before this honourable court and the public, especially the Bosniak public, for the crime that happened, and to apologize to the victims, their families, and the Bosniak people for my participation in that crime,” Nikolic stated in his confession. He claimed that, with his confession, he wanted to contribute to the truth about Srebrenica and its victims.

Erdemovic was the first person to admit guilt. He said he was sorry for all the victims, adding that he must confess because of them and because of himself. In his testimony, Obrenovic stated that his confession removed the responsibility from his people, and that he would be glad if he could contribute to reconciliation among peoples in Bosnia and Herzegovina. “I will be glad if my testimony helps the victims’ families by sparing them from testifying again and going through all the pain they would surely have to endure during their testimonies. My wish is for my testimony to help in making sure that this never happens again, anywhere,” he said.

“We conducted an analysis, and we came across information that, after being released, each one of them, without exception, went back to the original stands they had before filing their early release requests,” said Murat Tahirovic, president of the Association of victims and witnesses of genocide, claiming that the defendants did not speak the truth. Representatives of victims handed this analysis over to the Hague tribunal, which said it took it into consideration when deciding on defendants’ request for early release.

Establishing genocidal intent

Almost immediately, i n July 1995, the ICTY filed indictments against 24 individuals, including Karadzic and Mladic, on what had just happened in Srebrenica. The indictments, for individuals directly responsible for the atrocities against the population of Bosnian Muslims in the protected zone of Srebrenica, were filed again on November 16, 1995.

They were confirmed by judge Fouad Abdel-Moneim Riad, who said that the evidence presented by the prosecution described scenes of unimaginable barbarism, where thousands of men were executed and buried in mass graves, hundreds were buried alive, men and women mutilated and slaughtered, children killed in front of their mothers, a grandfather forced to eat his grandson’s liver. “These are true scenes from hell, written on the darkest pages of human history,” judge Riad said in November, 1995.

After having been indicted, Mladic was on the run for 16 years. He moved to Serbia in 1997, and members of the Serbian Special Police Unit arrested him in the village of Lazarevo, on May 26, 2011. He was then extradited to The Hague, and his trial began a year later. In his capacity as former Commander of the Main Staff of the VRS from May 12, 1992 to at least November 8, 1996, he was sentenced in 2021 to life imprisonment for genocide, crimes against humanity, and violation of the laws and customs of war.

A similar scenario occurred in the case of Karadzic, former president of Republika Srpska, who was in 2019 sentenced to life imprisonment for genocide and other war crimes committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Karadzic lived in Serbia under the false name of Dragan Dabic, who practiced so-called bioenergetic medicine, in the Novi Beograd neighbourhood and was arrested on a public transportation bus.

In the Mladic and Karadzic judgments, the genocidal intent has been established. It has been clearly said that, when a genocide is based on the intent to ‘partially’ destroy a group, it must be a substantial part of that entire protected group.

The Krstic judgment stated that the intent to destroy a group “as such” makes genocide a particularly grave crime, and this is what differentiates it from other grave crimes like, for instance, persecution as a crime against humanity. “The term ‘as such’ is very significant because it shows that the crime of genocide requires the existence of an intent to destroy a group of people who have a certain group identity based on national, racial, ethnic, or religious affiliation,” the verdict states, adding that members of the main staff of the VRS planned the killings of male prisoners fully aware of harmful consequences that this could have on the survival of the Bosnian Muslim community.

The ICTY, a critical reference for national judges

The Krstic judgment also established that, in July 1995, between 7,000 and 8,000 Bosniaks from Srebrenica and its surroundings were killed, and that a large number of women, children and the elderly were forcibly relocated. After the executions, the victims were buried in primary graves, and later they were dug out and reburied in secondary graves during September and October 1995, of which numerous pieces of evidence were presented before the court in The Hague and later also in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BIH).

Azra Miletic, former judge of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, consider that trials in Bosnia and Herzegovina and passing of verdicts for genocide and other crimes in Srebrenica wouldn’t be possible without the case-law of the ICTY. She states that case-law is not a source of law, but it is an important factor when comparing factual and legal situations.

“The Hague tribunal built its case-law to which we initially referred the most, because we had no other source of law related to war crimes. You know that we had never judged such acts before,” Miletic said, recalling having been the first domestic judge in an appellate chamber along with two foreign judges. She recalls that it was necessary for multiple cases to be completed in second instance for them to be considered a relevant case-law.

Trials that last an average of five and a half years

After having been indicted in the Hague in 2006 for genocide, crimes against humanity, and violation of the laws or customs of war, Milorad Trbic was accused on an expanded indictment of the state prosecution before the Court of BIH. In his capacity as assistant chief of security with the VRS Zvornik Brigade, he was one of the leader of the military police in Srebrenica in July 1995.

His case was the first to be transferred to Bosnian authorities for further prosecution. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison before the State Court, and is currently serving his sentence. The Court of BIH found Trbic guilty of having participated, between July 10 and November 30, 1995, in a joint criminal enterprise and operations to capture, detain and execute Srebrenica residents, as well as to hide their bodies.

The trial of Trbic lasted from November 2007 to February 2015. According to data collected by Detektor, trials for genocide and other crimes in Srebrenica conducted before domestic and international courts lasted on average five years and a half.

The longest trial, due to a repeated proceeding, lasted 15 years before the ICTY. It was the trial of Jovica Stanisic and Franko Simatovic, former leaders of the State Security Service of Serbia. They were sentenced, among other crimes, for the murder of six Bosniak captives from Srebrenica, committed by members of the Scorpios paramilitary unit in Trnovo in July 1995.

28 convictions in Bosnia for Srebrenica

Besides Trbic, the Court of BIH also sentenced Radomir Vukovic, Aleksandar Radovanovic, Branislav Medan, Brano Dzinic, Slobodan Jakovljevic, Milenko Trifunovic, Mendeljev Djuric, Zeljko Ivankovic, Slavko Peric, and Ostoja Stanisic for genocide in Srebrenica.

The longest prison sentence given by the Court of BIH was 35 years for Franc Kos, for crimes against humanity. Kos testified in his defence in this case, and the Court stated in the judgement that he disclosed a certain number of facts that had not been previously known, and expressed remorse for what he had done. In his testimony, he stated that he led a group that committed the killing of men in the military farm Branjevo, near Srebrenica, where he actively participated in the shooting and “verified” the death of those injured.

“People who were brought there were blindfolded, some of them wailed, some moaned, some cursed, but generally speaking, they headed towards the execution site calmly,” Kos testified.

According to the verdicts, about 800 people were killed at Branjevo on July 16, and it has been established that members of the Engineering Company of the Zvornik Brigade took part in the excavation of mass graves at this site on July 17.

The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina sentenced 28 people to a total of 464 years in prison for genocide and other crimes committed in Srebrenica. There are five ongoing cases before this Court for crimes committed in Srebrenica.

One of them has been on a break for three years due to inability of defendant Mile Kosoric to participate in the proceeding. Kosoric is accused, in his capacity as commander of the Vlasenica Brigade of VRS, of having stopped vehicles in the village of Luke together with other members of this unit, and seized money and gold from civilians, then directing them towards Kladanj. As stated in the indictment, members of the Vlasenica Brigade separated women and raped them, and shot dead 21 captured men in Mrsici on the night of July 13-14, 1995.

“It’s increasingly difficult to prosecute the remaining individuals”

From the end of 2023 to mid-2025, the prosecution of BIH filed four indictments against 22 people, in relation to Srebrenica. The indictments relate to events in the villages of Bisina, Kozluk, Orahovac and Milici.

Ibro Bulic, former state prosecutor, believes that there is still a need to draw on the established judicial facts, but time is not a good ally in processing war crimes. “My impression is that it will be increasingly difficult to find evidence and prosecute the remaining individuals who were involved in the genocide,” Bulic said.

Tahirovic, president of the association of victims of genocide, points out that a more serious approach to prosecuting war crimes is needed, and he does not believe there is a lack of witnesses, considering the rulings of the Hague tribunal in which there is evidence and on the basis of which investigations could be initiated. “Evidence can be used. They have become case-laws; it is only a matter of will and desire to initiate that,” Tahirovic says.

For former judge Miletic, trials run slowly and indictments are of lower quality. “When you have a poor indictment, there is no quality trial. I can immediately see what is not described. When you fail to describe an act, you cannot prove it during the proceedings,” Miletic said about the deficiencies in the current war crimes processing.

Escape of those accused of genocide

The ICTY and the Mechanism have now completed their work on cases for war crimes in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The remaining task is to support the domestic judiciary in doing its part, prosecutor Serge Brammertz said during an earlier visit to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“Since the constitutions of those countries prohibit the extradition of their citizens to other countries […] the only way to achieve justice in these cases is to transfer the criminal prosecution to countries where the suspects are located,” Brammertz said, commenting on the war crime defendants living outside of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In 2021, Milomir Savcic, president of the Veterans’ organization of Republika Srpska, became the first indictee for the Srebrenica genocide to become unavailable during the proceedings. Savcic pleaded not guilty of the allegations against him, in his capacity as commander of the 65th Protective motorized regiment of the main staff of VRS, of having planned, commanded and supervised the activities of his subordinates during the capture of several hundreds of Bosniak men in the area of Nova Kasaba. But when Savcic was ordered into custody, he fled, and an international arrest warrant was issued. It is assumed that he went to Serbia.

A significant number of war crimes suspects and defendants are in Serbia, which prevents their further prosecution. The practice of filing indictments against individuals unavailable to Bosnian judiciary was previously pointed out by judge Joanna Korner, a former prosecutor at the ICTY, in her two reports, in 2016 and in 2020, on the processing of war crimes in Bosnia and Herzegovina. She believes that by filing indictments against fugitives, resources are unnecessarily spent that could otherwise be used for alleged perpetrators residents in the country.

Domestic prosecutors did not agree with this assessment, explaining that it was important to file an indictment for every crime, for the sake of victims and facts.

Six convictions in Serbia for Srebrenica

In cases that have so far been transferred to Serbia for crimes committed in Srebrenica, six verdicts have been reached.

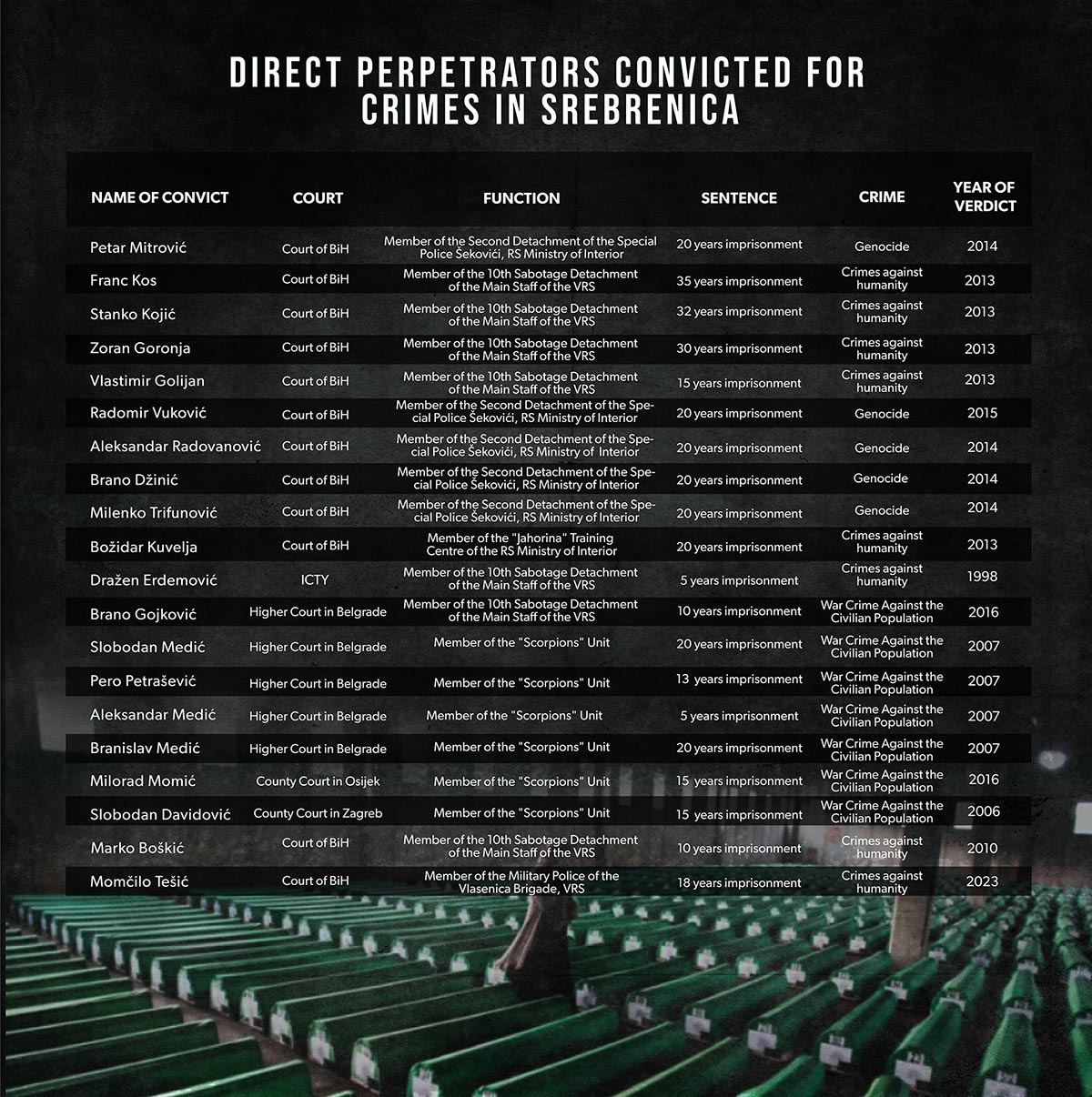

Brano Gojkovic, former member of the Tenth sabotage squad of the VRS, was sentenced in Serbia to 10 years in prison after pleading guilty and concluding a plea agreement for the murder of several hundred Srebrenica residents at Branjevo military farm on July 16, 1995.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kos was sentenced to 35 years for his participation in this crime, Stanko Kojic to 32, Zoran Goronja to 30, and Vlastimir Golijan to 15 years in prison.

In Serbia, former members of the Scorpios – Slobodan Medic, Branislav Medic, Pero Petrasevic and Aleksandar Medic – were sentenced to a total of 53 years in prison. The judgment states that the murders of Srebrenica residents near Trnovo were committed during “the civil war in the then Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina fought between members of the armed forces of Serbian, Croatia, and Muslim ethnicity”. In Croatia, former members of the Scorpios – Milorad Momic and Slobodan Davidovic – were sentenced to 15 years in prison each for the killing of Srebrenica residents near Trnovo. The footage of the killings, which became available to the public in 2005, remains one of the most disturbing pieces of evidence of the crimes in Srebrenica, and part of the collective memory in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as in Serbia, of the cruelty of genocide.

* Detektor is a media of the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network Bosnia and Herzegovina (BIRN BiH) dedicated to reporting on war crimes, transitional justice, corruption, digital rights, foreign influence and human rights in general.