Last week, the Federal Criminal Court of Bellinzona heard the final pleas in the Swiss trial of a former Gambian minister. Ousman Sonko’s lawyer asked for his acquittal and compensation amounting to almost a million Swiss Francs - 929, 855.25 CHF -, which is almost an equivalent amount in euros.

The public prosecutor and the plaintiffs’ lawyers were given the floor to react afterwards. The plaintiffs' lawyers - Caroline Renold, Annina Mullis, Nina Burri, Stephanie Motz, and Fanny De Weck - all maintained that Sonko was not in the dark about the crimes perpetrated under his responsibility.

The plaintiffs’ “exaggerations”

In closing remarks, the defence pleaded that the prosecution did not bring proof of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population in The Gambia, as described in the indictment.

“The plaintiffs have come before your court to deliberately describe an absolutely catastrophic situation throughout Yahya Jammeh’s presidency. They naturally have an interest in portraying things in the bleakest possible light, exaggerating the negative elements and ignoring their own misdeeds,” argued defence lawyer Philippe Currat. “They feel all the more free to do this because none of you three [judges] have ever been to The Gambia and have no experience of the situation on the ground at the time of the events.”

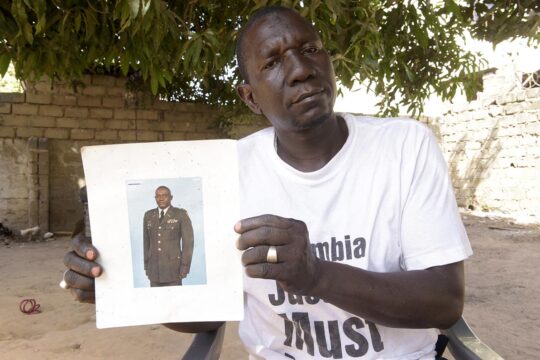

For him, an attack within the International Criminal Court’s definition of a crime against humanity is absolutely impossible to claim, as there was no concrete threat to the civilian population in The Gambia. “None!” he exclaimed, before coming back to the key testimony of Binta Jamba, the widow of Almamo Manneh, a State Guard soldier said to be loyal to Jammeh at the time. Ousman Sonko is accused of complicity in Manneh’s murder by luring him into an ambush in 2000.

“Madam Federal Prosecutor, you asked my client why Binta Jamba [who accused Sonko of raping her multiple times] would lie and he replied that she could better tell you the reasons. However, the reasons are obvious: her husband apparently died trying to resist his arrest. She holds Sonko responsible. Her husband’s failed coup deprives her of the opportunity to become the country's first lady, as she might have wished if he had succeeded. Of all the private plaintiffs we heard in this trial, she was the only one whose emotions - which were rare, by the way - did not appear sincere,” said Currat.

He further pleaded that there was no unifying link between Manneh’s death, the acts described by Jamba, the punishment of the March 2006 coup attempt, the death of Baba Jobe and the punishment of the “illegal” demonstration of 14 April 2016, which are all described in the indictment as a continuous offence of which Sonko is accused.

Manneh’s death, Currat argued, could be the result of a proportionate use of force. “The use of lethal force to arrest a high ranking army officer in a coup attempt who opens fire on the forces that have come to stop him cannot a priori be considered murder or homicide,” he pleaded.

“Journalists were free” under Jammeh

Currat also told the court that during the trial, the private plaintiffs submitted numerous copies of newspapers published in The Gambia between 2000 and 2016, which he said proves that “journalists were free to write and publish articles, including articles critical of the government, even on the most sensitive topics affecting national security, such as on persons involved in a coup attempt or investigations conducted after such attempts, on persons detained or possibly ill-treated in these circumstances.”

Referring to the indictment, Currat said it could be ruled out that Musa Saidykhan and Madi Ceesay were arrested and interrogated because they were journalists. For him, they were arrested “because they had published a false report that earned them a complaint from the person they had falsely portrayed as being involved in the coup. Without the complaint, there is no evidence that they would have been targeted.”

Currat didn’t mention that according to Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) findings, there were over 140 arrests and detentions of media practitioners under Jammeh’s regime, which, according to the TRRC report, “shows a deep-seated intolerance for freedom of expression and the media exercising its functions of promoting public participation, accountability, and democracy, as he viewed this as a threat to his power”.

“Torture is never permitted, torture is never legitimate, torture is never acceptable,” Currat kept on saying on Wednesday March 6, before the floor was given to the prosecutor and plaintiffs’ lawyers to respond the next day.

Prosecution reaction

“What a blind person can see but the defendant refuses to admit is that he was one of the central figures in the state apparatus of Jammeh’s regime of torture and terror,” said public prosecutor, Sabrina Beyeler. “The defence’s introductory statement has made it clear that the defendant, since the beginning of the trial, has an aim to politicize the proceedings.”

The defence lawyer accused TRIAL International, the Swiss NGO that initiated the case, of pushing their agenda to bring Jammeh to justice through this case. “Ousman Sonko is only a means to this end,” Currat said in his closing arguments.

“The trial is not political,” Beyeler stressed. “The only person who makes it a political issue is the accused. It is arrogant, presumptuous and defamatory to suggest that a non-governmental organization is acting as a whistleblower and that the courts in Switzerland would wave the trial through with a conviction for nothing, so that the criminal proceedings against Yahya Jammeh could be conducted as the ultimate goal.”

Annina Mullis, the lawyer representing Binta Jamba, retorted that the defence’s speculations about Jamba’s motivations for falsely accusing Sonko, may exist within the world view and logic of the accused, but are not very plausible outside of it.

She is also representing Madi Ceesay and Musa Saidykhan, two journalists tortured in March 2006. “There, I have already explained in detail the persecution of journalists and media organizations classified as critical. I would like to vehemently reject the claim that my clients themselves said that they were not persecuted and tortured as journalists. In court, both stated that they had been arrested and tortured in connection with their journalistic work - both also stated that their position within the Gambian Press Union had an influence at the time of their arrest,” she told the court.

Caroline Renold, a lawyer for three other plaintiffs – Bunja Darboe, Demba Dem and Ramzia Diab – refuted the defence’s statement that the victims are not part of the civilian population because they were coup plotters. “This element alone shows that the 2006 repression was an attack against the civilian population and not a criminal case against coup plotters,” she added.

Plaintiffs’ criminal behaviour?

Currat also accused the plaintiffs of having an interest in making people forget the criminal nature of their behaviour. “Almamo Manneh is not a poor, innocent victim, he was one of the highest ranking officers in the Gambian army and was involved in a coup attempt,” he told the court. “Bunja Darboe is not innocent either, as he was also involved in a coup attempt against the legitimate government of the country. Obviously, none of them had the aim of promoting human rights when organizing their coups. Musa Saidykhan and Madi Ceesay had published false information. Baba Jobe was a war criminal who was on the United Nations Security Council sanctions list for his involvement in the illicit trade in blood diamonds in connection with the civil war in Liberia and Sierra Leone.”

On that Wednesday, Sonko looked more anxious than ever. He had in front of him a document he was reading thoroughly. During breaks, he would get up, with his hands in his jumper pockets, and look up at the ceiling as if waiting to be saved. During one of the breaks, the public prosecutor came towards the podium to speak to the accused, and they seemed to have a friendly conversation.

No translation, no comment

On Thursday, the defendant appeared a bit less anxious but still tense, busier than ever. There was a pile of documents in front of him, and he was using his marker on the pages. When Sonko was finally given the floor, he first expressed his disappointment with the court for “refusing” to provide him with translation from German, the language in which the final pleas were expressed, to English.

He started to say that he could not comment on the pleadings because he did not know what was said against him, due to the lack of translation. He however told the court he noticed that the complainants amended their earlier statements. “I regret that they discredited themselves in this way by lying, with the sole aim of supporting the accusation against me, in defiance of the truth. I don’t blame them and I understand how important this trial is for them.

“There is an African dictum that says: ‘justice is not justice if in your journey to seek justice you kill an innocent person as a way for you to get to the person that actually hurt you’,” the former interior minister added.

“You have detained me for more than seven years without trial and in undignified conditions,” he told the court. “The legality of which no Swiss authority has ever been willing to examine. I have been held in solitary confinement for almost two years, which has had a serious impact on my health and, in particular, has caused permanent damage to one of my eyes, which is therefore a crime under Swiss law.”

“A history of colonialism and racism”

“You seem to be interested in what has happened in my country, the conditions in its prisons, the actions of its police and its authorities. You take a condescending view of the resources available to us in government to try to ensure its development. Naturally, and probably without really thinking about it, you are part of a history of colonialism and racism. You have to understand that we can’t work miracles under these conditions. If a country as rich and developed as yours is unable to provide its prisoners with dignified conditions of detention, how do you expect us to be able to do so?” he asked.

“For seven years, I have experienced hatred, contempt and lies from your criminal prosecution authorities. After seven years in pre-trial detention in Switzerland, I have the impression that your judicial system is based on arbitrariness, and systematically condemns foreigners. You have let me express myself to you more than at any time in the last seven years, but I don’t know if you have heard me.”

Parties now await the verdict, the date of which is as yet unknown.