JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

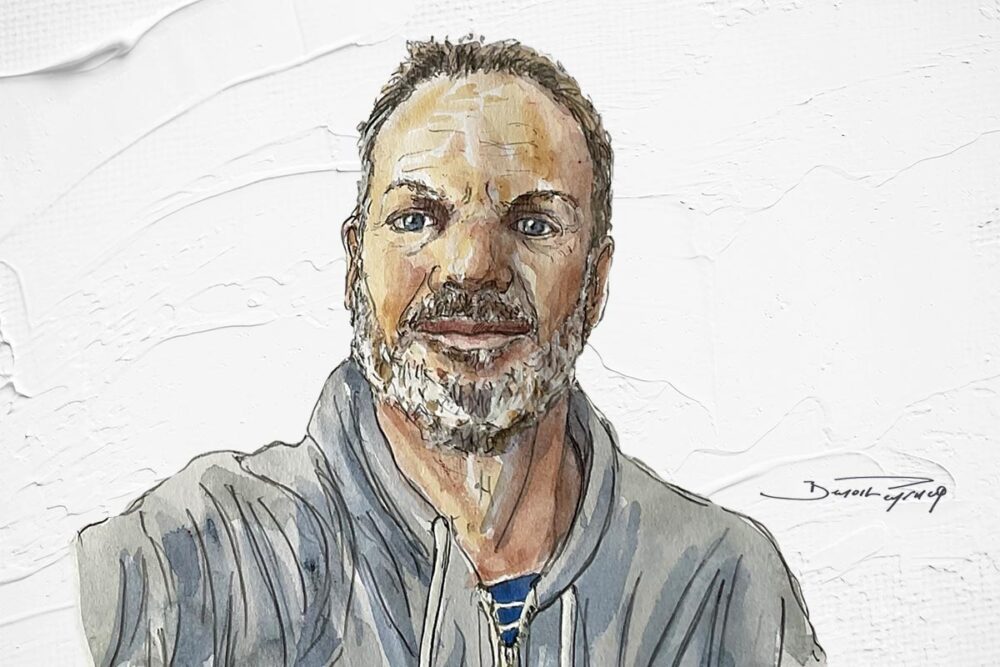

Guillaume Mouralis

Historian and director of research at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) in France

When international justice is lacking, citizens’ tribunals appear as a means of kick-starting justice when the will of States is not there. The historic model of the Russell Tribunal in 1967 established that the Americans used prohibited weapons during the Vietnam War, as French historian Guillaume Mouralis points out. He recognizes in today’s emulators a similar blend of legal rigour and creativity.

JUSTICE INFO: Why are you writing now about the Russell Tribunal held in 1967?

GUILLAUME MOURALIS: I've been working for many years on mass-crime trials held after a conflict or change of political regime. My thesis focused on the trials of former German Democratic Republic officials and agents following German unification. I then published a book on the Nuremberg Trials, in which I examine the limits imposed on the trials’ American designers when they defined the main categories of international criminal law – especially the crime against humanity, created for these trials. I then turn to how activists and artists appropriated and drew on these trials after 1946, particularly the Russell Tribunal which, in 1967, sought to confront the Americans with the principles they themselves had drawn up for Nuremberg. The Vietnam War constituted a major departure from these principles.

Through the Russell Tribunal, I want to show that international law is also constructed, interpreted and practised by unofficial actors, and is not just a matter held in the hands of recognized specialists. Law and justice can be powerful instruments of emancipation and liberation. It was therefore interesting to study in detail this original experiment in subjectivation of international criminal law, at a time when there was no permanent tribunal capable of judging international crimes. What’s more, this judicial experiment was the starting point for a rich tradition of citizen justice, which continues to this day.

What are the origins of the Russell Tribunal?

After the Nuremberg Trials in 1946, the United Nations considered setting up an International Criminal Court. But due to the Cold War and the refusal of the big powers, the USSR and the USA, the project was buried and only revived in the 1990s, leading to the creation of the ICC. The idea of British mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell was to create a tribunal modelled on the Nuremberg Tribunal, believing that, in the absence of a permanent international jurisdiction capable of applying international criminal law, it was up to citizens to seize this right and enforce it.

Members of citizens’ tribunals generally take international justice seriously"

How does this tribunal differ from “official” tribunals?

It was a self-proclaimed tribunal, not official. This is the principle behind the citizens’ tribunals that were to multiply in the years to come. They are set up outside international organizations and bodies by ordinary citizens, even if they often include jurists. Members of citizens’ tribunals generally take international justice seriously: they carry out in-depth investigations, gather evidence, and follow precise procedures. The aim is to pass judgment only after thorough investigations have been carried out, using expert opinions and reliable testimony wherever possible. Once these counter-investigations have been conducted, public sessions are organized where the evidence is presented before a jury.

While these tribunals claim to imitate international justice, they obviously do not have the same resources at their disposal. In practice, they differ from official tribunals: on the one hand, not all parties traditionally represented in a trial are present, and there is generally no defence. Most of the time, the accused States refuse to play the game, do not send a lawyer and do not present arguments. On the other hand, there is a kind of confusion between the functions of judging and prosecuting, between the judge and the prosecutor, with the jury taking it in turns to assume these two usually separate functions. The other major difference is that a citizen’s court does not have the power of coercion: it cannot make arrests or carry out searches, nor can it force witnesses to appear, and so on. They are weak courts, aware of their weakness from which, paradoxically, they try to draw their strength.

The idea was to choose indisputable, credible personalities; in France, they approached Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, who became the Tribunal’s executive president."

Tell us about the Russell Tribunal...

Bertrand Russell was born in 1872. That made him 95 years old in 1967! He was an intellectual who became known for his pacifism, having refused to serve in the First World War. In the early 1960s, he founded the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, dedicated to supporting all countries suffering from imperialist aggression. He was supported by a team of young, radical Third World activists with close ties to Che Guevara and Cuba. It is important to understand that the Russell Tribunal was highly politicized from the outset, and took this on board, demonstrating that it was not incompatible with a judicial approach. This assumed politicization has provided arguments for all those who have criticized the Tribunal, denouncing it as biased from the outset.

In 1966, Russell set up an international jury of 24 intellectuals, writers, political and trade union leaders representing 18 nationalities, half from the Western world and half from the “global South” (Japan, Cuba, Pakistan, Philippines, Turkey and more). Among the first group were three African-American leaders. The idea was to choose indisputable, credible personalities; in France, Russell approached Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, who became the Tribunal’s executive president. Once the jury had been constituted, the organizers set up collective fact-finding missions to Vietnam, made up of experts - doctors, chemists, agronomists, historians, and lawyers. They were representatives of the radical “New Left” and Third World revolutionaries not aligned with the Soviet Union.

The USSR, the countries of Eastern Europe and China did not support the Russell Tribunal. Not surprisingly, such a “citizens’” initiative was viewed with suspicion by these authoritarian countries. As for the American government, it became concerned about the Tribunal in the summer of 1966, and organized a counter-propaganda campaign involving the State Department, the FBI, the CIA and military intelligence. In the United States, this operation was a success, judging by the very negative media coverage of the Tribunal’s activities and the ad hominem attacks against Russell.

How did the investigations and public sessions work?

Bertrand Russell and his secretary Ralph Schoenman, linchpin of the Tribunal, were in contact with the North Vietnamese authorities and the Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (FNL), which facilitated the Tribunal’s investigative work. The Vietnamese authorities hosted five collective fact-finding missions on their territory, so that the investigators could see for themselves the war crimes committed by the US army. On site, they showed the investigators civilian sites bombed by the American air force that were clearly not military targets (dams and dykes, schools, hospitals, etc.).

The investigators questioned, photographed and took bomb samples. The Russell Tribunal provided proof that the US army was making massive use of weapons prohibited by the laws of war: chemical weapons and cluster bombs, which had no direct military purpose and needlessly maimed civilians. Physicist Jean-Pierre Vigier produced a highly detailed report on this last category of weapons, forcing the American authorities to acknowledge the “limited” use of “cluster bomb units”. The Tribunal’s investigative work was therefore serious and detailed, and is documented in detail in the minutes of the trial, published in several languages (two volumes - almost 800 pages - published in French by Gallimard).

Attacks on civilian populations were massive in both North and South Vietnam. There was indiscriminate bombing in the north, large-scale forced population displacement in the south: hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese were moved to what the Americans called “strategic hamlets”, described by the Russell Tribunal as “concentration camps”. There was also widespread torture by American military intelligence.

The Russell Tribunal then organized two public sessions. The first -- in Stockholm, Sweden, from May 2 to 10, 1967 -- examined two legal questions: had the US government committed acts of aggression against Vietnam, thereby rendering itself guilty of that major crime under international criminal law for which the Nazis were reproached at Nuremberg and the Japanese at Tokyo? Was there bombing of purely civilian targets that did not correspond with military imperatives? The second session took place in Roskilde, a suburb of Copenhagen, from November 20 to December 1, 1967. It examined the following three questions: had the US armed forces used weapons prohibited by the laws of war? Were prisoners of war and civilians subjected to inhumane treatment prohibited by the laws of war? Was the US government guilty of the crime of genocide against the Vietnamese people?

Who attended these sessions?

During these two public sessions, over a hundred witnesses and experts were heard by the jury: experts who had taken part in the commissions of inquiry, but also journalists, photographers and famous film-makers. Many images were projected: the screen occupied a central place in the setting of the trial. A large, militant and participative audience attended the sessions. In this way, the sessions stood out from the solemnity of official tribunals.

Among the witnesses were eight Vietnamese. In Stockholm, they showed the jury their wounds in a somewhat demonstrative manner. They included Do Van Ngoc, a 9-year-old child burned by napalm, who agreed to be stripped naked. The testimony of schoolteacher Ngo Thi Nga, injured by a cluster bomb, was another highlight of the trial. These testimonies, reported by the press, left a lasting impression. The Russell Tribunal paid close attention to types of violence that were scarcely mentioned at the time: violence against children, sexual and gender-based violence against women. It was only much later that international texts would specify and define these types of violence. Moreover, the specifically racist dimension of American war crimes in Vietnam was amply underlined by the experts and ultimately by the jury, who also demonstrated the precarious situation of African-Americans in the American army. The Russell Tribunal thus showed itself to be a forerunner in dealing with crimes that are still relatively undefined.

During the second session, in Roskilde, three demobilized American soldiers testified before the jury. After a fact-finding mission to the USA, the anti-colonial lawyer Gisèle Halimi succeeded in convincing three soldiers, including a black soldier, David Tuck, to take the stand. They all spoke of the widespread practice of torture against prisoners of war, and emphasized that summary executions were commonplace. This was the first time that American soldiers spoke out publicly on the subject. Let’s not forget that 1967 marked the start of the American war in Vietnam; the anti-war protest movement would only gain momentum in 1968.

The Russell Tribunal declared that the US government had committed the crime of aggression."

What were the conclusions?

At the end of the first session, the Russell Tribunal declared that the US government had committed the crime of aggression as defined in 1945. It also concluded that the bombings had massively targeted civilian targets, in defiance of the laws of war. At the end of the second session, the jury found that prohibited weapons had been used, particularly chemical weapons such as defoliants, napalm and white phosphorus, the latter two causing irreversible damage and burning bodies from the inside out. It declared the American government responsible for inhumane treatment inflicted on prisoners and civilians, including mass forced displacement of populations, organizing prostitution of women, and large-scale sexual crimes. It concluded that this government was guilty of the crime of genocide against the Vietnamese people. In a dense, detailed and particularly remarkable text, Jean-Paul Sartre detailed the Tribunal’s reasoning on this crucial part of the judgment.

What are the value and potential scope of these conclusions?

The Russell Tribunal’s judicial and legal approach is not devoid of ambiguity. Initially, Russell announced to the press that US President Lyndon Johnson, his Secretary of State Dean Rusk and other American leaders would be tried by the Tribunal. This soon proved unrealistic and politically counterproductive. Indeed, the two Scandinavian countries which - unlike France and the UK - agreed to host the public sessions did so on condition that no individual charges would be brought against an official representative of a foreign state and ally.

The Tribunal therefore preferred to confine itself cautiously to establishing the general responsibility of the American government, without naming those responsible individually. This is almost always the case in the judgments of citizen tribunals. They generally forego individual incrimination within the logic of international criminal law, and adopt a more hybrid, legally indeterminate approach, applying international criminal law but without establishing individual responsibility.

Were these crimes ever examined by official courts?

As far as Vietnam is concerned, American war crimes were almost never examined and judged by national or international courts. There were a few trials of American soldiers before a court-martial, but these were very limited. The Russell Tribunal is the only more or less judicial body to have dealt with these crimes. Other citizens’ commissions of inquiry were subsequently set up in the United States. In the early 1970s, for example, a group of former soldiers conducted an in-depth investigation into American war crimes. The work of elucidating these crimes was first and foremost a “citizens’” initiative.

You prefer the term “citizens’ court” to the often-used expressions “court of opinion”, “people's court” or “people's tribunal”? Why?

The vocabulary isn’t very satisfactory. In France, the term “tribunal d'opinion” was used first, because the aim is to influence international public opinion by providing evidence that massive crimes have been committed in defiance of international rules. These tribunals are renewing the repertoires of collective action: they are replacing the classic moves of political mobilization - petitions, demonstrations and meetings - with a judicial or para-judicial approach, not excluding the others. They are a new tool for advancing militant causes.

In the Anglo-Saxon world, the term “people’s court” is often used - a problematic term, given the historical connotations of the tribunals set up by authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. Think of Nazi Germany, which had its People’s Court, or the Stalinist USSR. So, for want of a better expression, I prefer to call it a “citizens’ court”, even if the term “citizen” is a bit overused. We could also more accurately call it a “non-governmental tribunal”, because that’s what it is.

Whereas the Russell Tribunal on Vietnam assumed controlled politicization of international law, more recent citizens’ tribunals are more attentive to observing a certain judicial neutrality."

What does the Russell Tribunal have in common with today’s citizens’ tribunals?

The Russell Tribunal is a special case, partly distinct from subsequent citizens’ tribunals. There were five other “Russell” tribunals (supported by the Russell Foundation), the most recent of which was the Russell Tribunal on Palestine, from 2009 to 2014, in which Gisèle Halimi also participated. Whereas the Russell Tribunal on Vietnam assumed controlled politicization of international law, more recent citizens’ tribunals are more attentive to observing a certain judicial neutrality. In my view, it is the work of in-depth counter-investigation that is the strength of the most interesting citizens’ tribunals, such as that of 1967.

You followed the Uighur Tribunal held in London between June and December 2021, which concluded that genocide and crimes against humanity had been committed. How did you experience it, with the Russell Tribunal in mind?

The London Tribunal explicitly follows in the footsteps of the Russell Tribunal, continuing its legacy. But the way it worked was different. International jurists had a more prominent place on the jury; court president Geoffrey Nice was lead prosecutor at the trial of [former Serbian president] Slobodan Milosevic. Its legal work was undoubtedly more thorough: the Uyghur Tribunal in London tried to demonstrate that the Chinese government is responsible for the genocide of the Uyghur people. It did so on the basis of a close reading and very precise interpretation of the 1948 Genocide Convention. By contrast, in 1967, the category of genocide was terra incognita: at that time, it had virtually never been applied or interpreted by a court of law.

The Uyghur Tribunal was probably not able to carry out as thorough a field investigation as the Vietnam Tribunal, as access in China is by definition impossible. The Chinese authorities forbade any investigation. Investigations were based, for example, on “leaks” -- official documents leaked by whistle-blowers which revealed criminal practices. This documentation had to be analysed and interpreted, a painstaking and far-reaching task...

In 2021, as in 1967, the investigations were nonetheless rigorous and the legal creativity undeniable; the two tribunals thus proposed, each in their own way, a somewhat heterodox interpretation of genocide. On the one hand, as Sartre points out, in Vietnam, “the intention emerges from the facts”. On the other, in Xinjiang, the focus was on genocide by population reduction through brutal demographic engineering.

What about the Permanent People’s Tribunal?

The “PPT” (Permanent People’s Tribunal) was created in 1979. It was a project spearheaded by one of the Russell Tribunal’s leading figures, Italian socialist MP Lelio Basso, who played a very important role in the development of citizens’ tribunals. After contributing to the creation of a second Russell Tribunal on human rights violations by Latin American dictatorships from 1973 to 1975, Basso put forward the project - which would see the light of day after his death - of creating the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal: a permanent structure capable of organizing citizens’ trials throughout the world on any massive violation of human rights.

In its charter, the TPP combines a variety of legal sources: obviously, the classic international criminal law of Nuremberg, to which is added the category of genocide defined in 1948, but also sources less legitimate at international level, such as the right of peoples to self-determination. This is the originality of these citizens’ tribunals, which combine established bodies of legal doctrine with elements that are less so. More generally, they allow themselves a great deal of freedom in terms of legal and procedural issues. Today, the TPP is a small association based in Rome, which since its creation has facilitated the organization by human rights activists of over 30 trials concerning crimes past and present. It is an important player in the often overlooked sphere of citizen justice.

Historian Guillaume Mouralis is director of research at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) in France, member of the Centre européen de sociologie et de sciences politiques (CESSP), and an associate of the Marc Bloch Center in Berlin. He is currently preparing a book on the history of the 1967 Russell Tribunal, to be published in 2025.