The long-haul trial of two executives from Swedish company Lundin Oil is entering a new phase. After the statement of facts by the prosecutor and lawyers for the plaintiffs and defence, it is now the turn of the witnesses. The first batch of witnesses will be heard over a six-month period in room 34 on the second floor of the Stockholm courthouse. A second batch will follow from February to November 2025. But before victims’ voices are heard for the first time, the trial saw a major battle over evidence.

During the five months that the Swedish lawyers for former Swedish Lundin Oil chairman Ian Lundin and his Swiss ex-CEO Alexandre Schneiter took the stand, they sought to discredit some of the sources used by the prosecutor. These include authors of NGO reports described as aiming to mobilize opinion rather than serve as evidence in a trial; and journalists presented as not cross-checking their sources enough, relying on NGO reports or sometimes working not only as journalists but also for these NGOs. The defence also felt that the prosecutor was not specific enough to justify the indictments for complicity of war crimes in Sudan, lacking details on the alleged perpetrators of the crimes and on the places and dates they were allegedly committed.

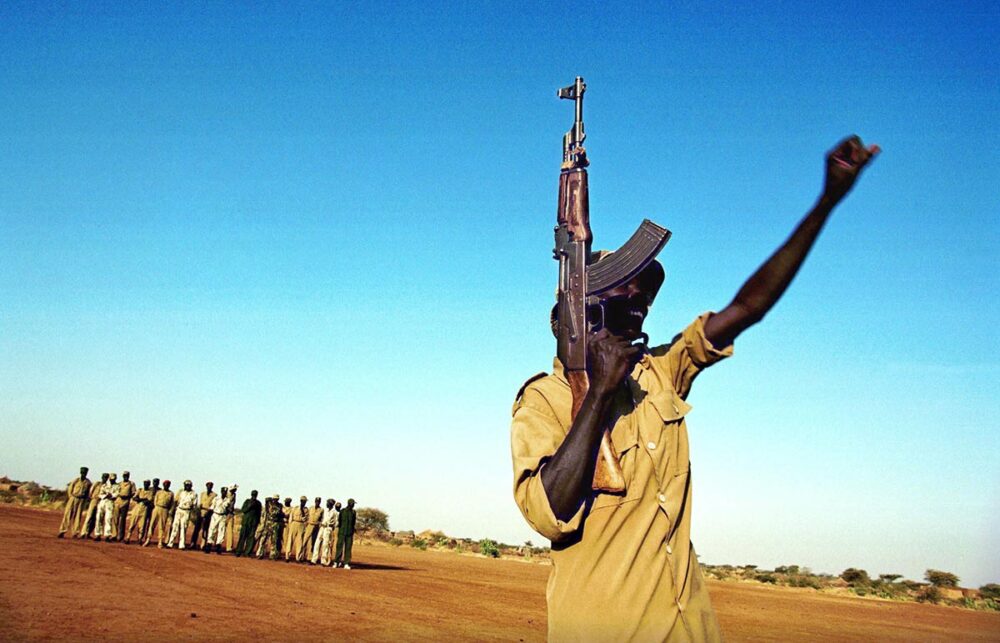

The prosecutor described the armed conflict as a struggle between the Khartoum government and the South Sudanese SPLA rebels for oil and independence, after the lawyers argued that there was no conflict between the government army and the SPLA in “Block 5A” when Lundin Oil was operating there. Any fighting was not caused by oil, according to the lawyers, but by inter-ethnic conflicts most often linked to cattle rustling. Such conflicts took place before Lundin’s presence in the area, continued during its presence between 1997 and 2003, after its departure and even since South Sudan gained independence in 2011, they argued.

While affirming this, the defence tried to downplay the actions of armed groups that may have clashed there. “Even if some of them are called ‘allies of the regime’, we know very little about these groups,” said one of the lawyers.

Double-edged reports

Faced with these two lines of defence – discrediting and minimising -, the prosecutor adopted an unexpected counter-attack strategy. Rather than trying to respond point by point to the accusations about NGO sources and press articles, he went to the defence’s own sources to find elements to resume the offensive. To provide new evidence, he analysed the reports of security companies hired by Lundin and other companies operating in the region, which the prosecutor had already used in part last autumn.

These famous documents come from searches carried out in January 2018 at Lundin Oil’s offices and at the homes of brothers Ian and Lukas Lundin in Geneva. They include internal security reports and letters from Christina Batruch, head of Lundin Petroleum’s Corporate Responsibility department in Geneva. For the prosecutor, they demonstrate that the loyalties between the militias and the main players, the Government of Sudan and SPLA rebels, were constantly changing. What’s more, according to the prosecutor, these internal reports themselves said that oil was decisive in the escalation of the conflict.

“Until 1997, Block 5A was relatively untouched by the civil war,” recalled the prosecutor Henrik Attorps. “The situation in Block 5A changed when representatives of the Nuer people felt that the Sudanese regime was not respecting the Khartoum Peace Agreement signed in 1997”, precisely when Lundin Oil arrived in this area now located in South Sudan. According to the agreement, the Sudanese army was not to operate south of the Bahr El-Ghazal River, in the northernmost part of Block 5A. When it crossed the river, it was considered an intrusion into southern territory, hence the start of the escalation and the conflicts via proxy militia between the between the SPLA and the Khartoum government.

“The [security firm] Control Risks Group,” said the prosecutor, “states in its July 29, 1998 security analysis that the [Khartoum] regime’s strategy for securing the oilfields was largely based on the [government's] ‘Peace from within’ plan”, with a first and then a second agreement with different rebel groups in the South. This plan had two phases, with a first and then a second agreement with different rebel groups in the South, “which constitutes a ‘divide and rule’ strategy,” the prosecutor continued. Another security report report, dated 1 May 1998, is even more specific, stating that “the SSDF [South Sudan Defence Forces, pro-government forces created under the 1997 Khartoum Peace Accords] are negotiating control of the company’s area of operations and thus future oil revenues.” For the prosecutor, this indicates the involvement of armed groups in what he calls “war by proxy” aimed at controlling oil revenues, not some clan vendetta caused by cattle rustling.

Defections and shifting alliances

In another report entitled “Conflict survey and mapping analysis” published in August 2002 by UNICEF, UNDP and the Sudanese Ministry of Higher Education -- often cited by the defence in recent months --, the prosecutor also drew information to support the same argument. “The army,” said the prosecutor, citing the conclusions of this report, “entered the region in violation of the peace agreement, after the discovery of oil by Sudan Ltd. [in which Lundin Oil was a stakeholder] in April/May 1999. The army’s actions in Block 5A were aimed at allowing the companies to carry out their oil operations under regime control. Militia leaders allied to the regime [in Khartoum] were in favour of oil operations and of the Lundin company, while rebels [groups affiliated to the South Sudanese SPLA] strongly opposed regime-controlled oil operations.”

There were many defections and shifts in alliances, and new armed groups emerged from splits. In light of these reports, it is hard to claim that calm reigned in Block 5A. Contrary to what the defence claimed, Lundin’s reports are according to the prosecutor full of precise details on these groups, their commanders, their allegiances, and they provide a detailed chronology of it.

These were all indications that Lundin’s leaders could hardly ignore. “The regime [in Khartoum] has, because of shifting loyalties in 2002, deployed more regular troops to Block 5A,” continued the prosecutor. “Given the economic importance of oil and the possibility of future revenues from Block 5A, the regime will do everything in its power to consolidate and extend military control over the oil producing areas”.

In the mouth of the prosecutor, this “everything in its power” makes the link between oil exploitation and war crimes, and sounds like a dramatic transition to the scenes of destruction described by the South Sudanese witnesses who are currently starting to appear before the Stockholm court.