As Liberia’s Office of the War and Economic Crimes Court (OWEC) celebrates its first year anniversary on 2 May 2025, victims and civil society groups are anxious about what has been achieved and what is the prospect of establishing the actual court. On 27 March 2025, members of the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET) staged a quiet protest at the OWEC. The protest action was twofold: to show solidarity to OWEC’s leadership and to question the government’s commitment to the process. Beyond the removal of Jonathan Massaquoi, the first Executive Director, and the appointment of Jallah Barbu, a former dean of Liberia’s prestigious Louis Arthur Grimes School of Law, little progress has been reported. Much of this has been attributed to funding. The lack of significant progress, however, cannot be simplified in the rise of Donald Trump, the dismantling of USAID and the US State Department mechanisms for funding. Neither can the limited work done in the first year be attributed to the old trope of post-conflict societies being overwhelmed by competing development priorities. The fundamental concern is that President Joseph Boakai’s expressed political commitment for civil war-era accountability is not being matched by adequate budgetary allocation.

Boakai’s desire to establish the court has been criticised by members of the elites. Former President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf has vehemently rejected the idea of the court as counterproductive to Liberia’s stability. Likewise, former President George Weah, though in the past a supporter of the idea, has recently questioned the timing of the court.

Signatories of the 2003 Peace Agreement, all of them former heads of warring factions, have also voiced strong opposition to the court. Hence, the government’s strategy of modest budgetary allocation in anticipation for foreign assistance is viewed as a ploy to shift blame and to attribute the limited progress as a direct result of donor fatigue.

The government’s minimal spending

The praxis of transitional justice has often informed that the more domestic spending is invested in dealing with the past the more it demonstrates a strong sense of national ownership while foreign assistance signals international validation. The European Union has stated emphatically that “they cannot spend money on such a process unless the government is fully behind it.” The EU response to OWEC, according to Barbu, suggests that the government must go beyond words and provide substantial financial support. Similarly, the US as indicated that they would like to see a process that is “Liberian-led and owned.” Even so, with the rise of Trump, a Liberian-led process might still attract little or no funding as the US support is no longer guaranteed.

Ironically, in the early days of transitional justice in Liberia, right after the civil wars ended in 2003, the hassle for funding was far less a concern compared to now. When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act was passed in 2005, Liberia’s annual budget was a measly US$19,117,491 million dollars. Yet, the Unity Party government under Johnson Sirleaf consistently provided a yearly 1.4 million dollars to the TRC. The Government of Liberia contributed more than 50% of its total cost of US$7.5 million. Twenty years later, when the national budget is US$861.8 million, forty-five times more than it was in 2006, the announced government financial support to OWEC pales in comparison.

In 2024, the Unity Party government under Boakai has allocated US$500,000 to OWEC, from May to December. Of this amount, Barbu and his team inherited US$368,000 from the Ministry of Justice, the oversight to OWEC, without a turnover note explaining how the other portion was used up. Report on work done is also not available.

In 2025, US$300,000 was appropriated to OWEC. To access this fund, the OWEC has to write to the Ministry of State (MoS). Then the MoS gets to write to the Ministry of Finance and Development Planning for the money to be disbursed. When the funds are approved, OWEC is required to write an invoice to the MoS before the funds are eventually made available. According to Barbu, the process takes weeks, sometimes more than a month. However, on April 30, Boakai renewed his Executive Order, less than 24 hours before its expiration. The new Executive Order contains a new budgetary appropriation of US$2 million dollars to be disbursed directly to OWEC’s account, a drastic change from the previous bureaucratic process. Since these funds are not allocated in the national budget passed four months ago, a supplemental appropriation will have to be made. It requires a simple resolution in the House of Representative. Yet, the sudden change of course, though welcome, is viewed more as a concession to international pressure rather than a deliberate strategy. Victims and civil society remained suspicious of the Government’s commitment especially in view of the growing elite opposition to OWEC.

Renewed resistance by national elites

The TRC process was less bureaucratic, and they received more funding from the national budget in one year than what OWEC is receiving in two years. At this level, the concern about commitment goes beyond the Presidency. In March 2024, the House of Representative endorsed the resolution establishing OWEC by 42 votes out of 73 while the Senate voted 28 out of 30. The support in both houses was powerful. Both the Senate and the House are critically involved in the budget process where every dime gets to be scrutinised. Members of civil society and victims hold two viewpoints on the low commitment towards OWEC. One, the strategy to fund the court was originally conceived through the goodwill of the United Nations and the United States, and that support is now in doubt. Two, elite consensus against the idea of the court is gaining traction and low funding and complex bureaucracy appear as deliberate measures orchestrated to frustrate the process.

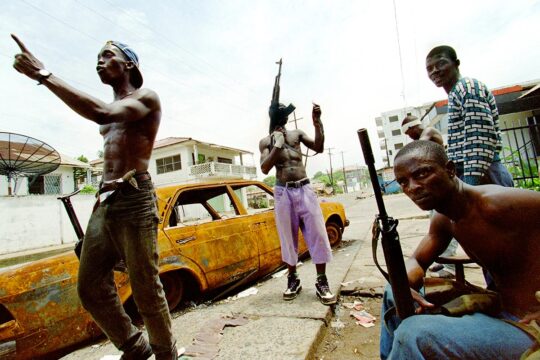

Talks about the establishment of a war and economic crimes court continue to arouse strong emotions. The signatories to the Peace Agreement have stated emphatically, that if you “touch one, you touch all.” This statement was made during the funeral ceremony on 18 January 2025 of senator Prince Johnson, a key warlord during the first civil war, by another senator, Thomas Yaya Nimley, who was the head of the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL), another warring faction. After Johnson, Senator Nimley has positioned himself as the most vocal anti-OWEC political leader. The statement was a threat that in the unlikely event any head/leader of a warring faction or a senior commander is arrested on account for war crimes, the risk of the country returning to conflict would be high, because it would be resisted.

Barbu was recruited with the guarantee of security protection. In an interview with me mid-April, he recalled that he saw the Emergency Response Unit, a special squad of the Liberia National Police (LNP), deployed at this office without his prior knowledge, before it withdrew without saying why. In a meeting with the Inspector General of the LNP, a promise of a 15-man security team to be assigned to OWEC and the chief executive was made; this too has not materialised. “My family members are worried about my safety,” Barbu lamented.

Preconditions for a successful court

On the one-year anniversary of OWEC, the work stream can be described in three parts. Firstly, the draft bill on the establishment of the war and economic crimes put together by the Liberia National Bar Association in 2019 is being revised based on reviews by experts. The draft bill envisioned the court as being subordinated to the Supreme Court of Liberia. With the pervasive practice of political interference in the judiciary, experts on comparative tribunals, hybrid and special courts, have highlighted this subordination as one of the major problems that ought to be addressed. Secondly, the United Nations Rule of Law Team has seconded a lawyer to the OWEC. The collaboration is geared towards model selection, i.e whether a special court, hybrid or national court would represent the most adequate model for Liberia.

A special court as was done in Sierra Leone is unlikely due to lack of funding and the fact that donors are rethinking that such model is not good value for money. Donors, including the UN, are more likely to support a process that is less expensive. OWEC is leaning more in the direction of a hybrid or national outfit, with a mandate that provides parallel authority to that of the national Supreme Court. Additionally, for the court to be successful an initial assessment of the availability of evidence and local capacity to drive the investigation are considered critical. More than thirty-five years after the civil war started, the prospects of evidence gathering are increasingly becoming grim. In this respect, the TRC archives relocated to Georgia Tech university in the US might be the silver lining. But the archives have not been assessed considering OWEC’s needs.

Local capacity is the next major challenge. The Louis Arthur Grimes School of law – the only law school that has produced Liberian lawyers – provides expertise in the practice of procedural law and the constitution, without the specialisation to grapple with the complexity of post-war justice and accountability. To proceed on a solid foundation, OWEC would need at least 50 Liberian lawyers trained in the rigor of criminal investigation, case file development and forensics, according to a Liberian jurist and an international criminal lawyer I talked to. For lawyers to be minimally prepared for this task, some accelerated academic programme would have to very quickly be customised to address this gap. Liberian law prevents non-Liberian lawyers for practicing in-country. A legal dispensation would have to be granted to allow both Liberian and non-Liberian lawyer to collaborate in court.

Finally, a strategic communication for OWEC is being developed. The purpose is to identify all the strategic stakeholders and audiences and develop the right messages to them with the view of increasing public confidence in the Office. One the stakeholder groups that OWEC is formally partnering with is Liberia Massacre and Survivors Association, LIMSA. A memorandum of understanding was signed on 14 April 2025 that allows for OWEC and LIMASA to undertake the joint implementation of projects related to victims and survivors of the civil wars.

Should the prospect of the court be determined to be grim due to limited evidence and low capacity, alternative measures of transitional justice as advanced in the TRC Final Report would be considered to offset the idea of the court.

Post-war politics and state building

Liberia’s post-war politics is consolidating. However, in this process, the elites’ interest have been served much more than ordinary citizens.’ Even though Liberian politics have radically shifted from minority rule to majority, the ground rules of mass accumulation of wealth remain the same. For example, the payroll from the Ministry of Finance and Development Planning revealed that the Speaker of the House earns US$22,850 and the deputy speaker US$16,075 as monthly salaries. Further interviews on salaries uncovered that the vice president of the country earns the same as the Speaker while the president earns US$25,000 monthly. Members of the House of representatives earn US$8,000 monthly, as do Senators. The Chief Justice earns about the same as the vice president while the four Associate justices earn slightly less.

Even though the Public Financial Management Law maintains that all income are taxable, the judiciary have negotiated that only 50% of their income can be taxed. In an interview with me, the former Director General of the Civil Service Agency (CSA) indicated that attempts to standardize the tax system like all other ministries, commissions and agencies provoked the fury of the judiciary. In an apparent act of intimidation, the Trial Judges Association of Liberia threatened to take the CSA to court. Their justification for a tax break was they have no other source of income and subjecting their salary to Liberia’s drastic tax system would be tantamount to reducing their pay. As a compromise, 50% was agreed to be taxable and the other half without tax. This information was corroborated in further interviews with senior officials (past and present) of the Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, a former Associate justice of the Supreme Court and a senior official at Liberia’s Internal Audit Agency.

Historically, the growth in Liberian revenue has served the interest of the elites over urgent development priority. In the 1960s, when the Liberian GDP grew so much that it was comparable to that of Japan, an academic survey critiqued the political economy as “growth without development.” More than sixty years later, Liberia’s search for justice appears to be undermined by this elite pattern of privilege and wealth accumulation even though the country has moved away from minority rule to majority.

AARON WEAH

Dr Aaron Weah (no relations to former President George Weah) is the director of the Ducor Institute, a Liberia-based think tank. He is a civil society activist, a transitional justice scholar, and the co-author of “Impunity Under Attack: Evolution and Imperatives of Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission”. Weah holds a PhD from the Transitional Justice Institute at Ulster University, United Kingdom. He’s specialised in memories of political violence and the impact on society. He is also teaching negotiation and conflict resolution at Liberia’s Foreign Service Institute.