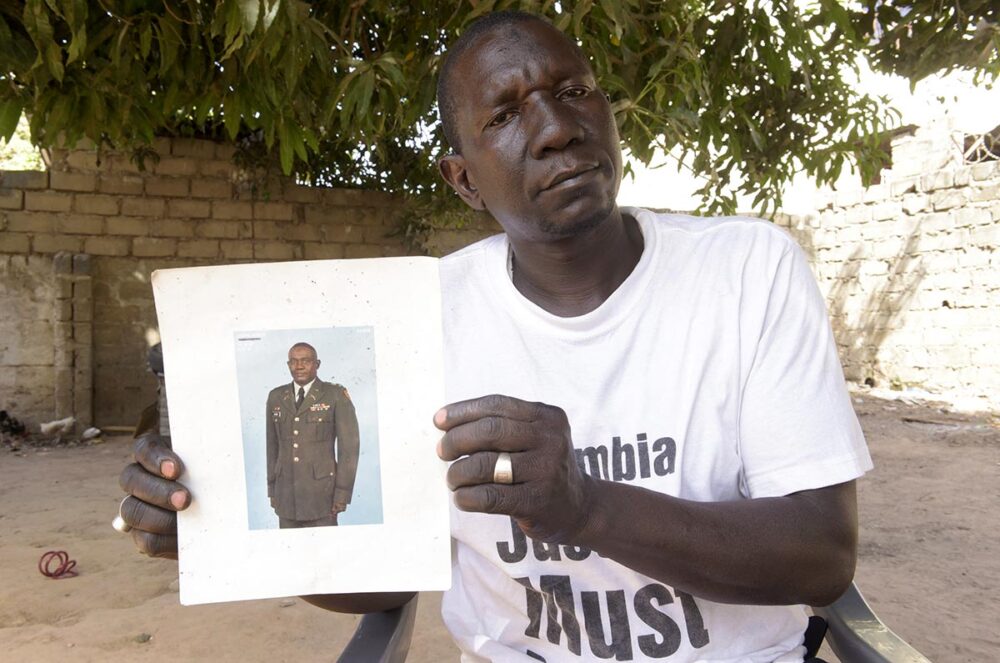

For twenty-two years, the family of Cadet Amadou Sillah lived in a suffocating silence. When he was killed during the bloody events of November 11, 1994, his family could not even openly mourn due to the hefty price the then leader of The Gambia Yahya Jammeh placed on dissent. Today, they sit in the heavy realisation that the state has finally put a price on Amadou’s life. “This is literally his blood money,” says Mamudu Sillah, Amadou’s brother. “It was like the government had come to commiserate with us, but no one could ever pay for the soul of another.”

Cadet Sillah’s family is one of many families receiving their complete reparation payment from the Gambian government's newly established Reparation Commission which started disbursing 20 million dalasis (274, 000 dollars) allocated for the 2026 budget cycle.

The Reparation Commission’s current phase is strictly chronological, targeting 83 identified victims from the 1994–1996 period (Jammeh’s dictatorship last from July 1994 to January 2017). The payment policy which determines who gets what and what crime was perpetrated was formulated by the national Truth, Reconciliation and Reparation Commission (TRRC) in 2020, shortly before the TRRC concluded its final report after two and a half years of public hearings. The Truth Commission selected 1.009 victims for its reparation payout scheme, something which was to cost little over US$4 million in total.

Due to the shortage of funds, the Commission could only pay 19% to each victim’s entitlement. Now, Sillah’s family received their complete payment— D600,000 (about 8,200 USD) — the amount put on extra-judicial killings and disappearances by the Truth Commission. A torture victim Abdoulie J. Darboe also received his full payment— D195,000 (about $2,670) — the price placed on torture by the Truth Commission.

The funding gap

The new Reparation Commission’s work is currently tethered to the D20 million government allocation, of which only D6 million (82,000 USD) has been disbursed so far. The leftover D14 million (about $187,000) is approved by the Reparation Commission and is being paid to the bank accounts of the victims through the Central Bank of the Gambia.

A fraction of the total proceeds from the sale of the assets of Jammeh is earmarked to support the process. The Gambian government has declared receiving over $20 million from the sale of these assets which were seized by the State. Less than a quarter of this amount – 4 millions – would have paid the entire reparation identified by the TRRC. However, there are still no publicly available data on how the government has spent this amount.

The U.S. government recovered $3.5 million from the sale of Jammeh’s mansion in Potomac, Maryland. While intended for the victims’ fund, the Commission confirmed to Justice Info that these funds have not yet been received. “The Commission is currently unable to provide a timeline for this,” officials stated, noting that the Ministry of Justice is still facilitating the transfer. Until that money arrives, the Commission remains reliant on a limited national budget to settle claims for identified victims.

Meanwhile, the Reparation Commission has officially begun registering new victims who were not captured during the initial TRRC hearings. While this offers hope for many, it also expands the reparations the state owes. “The Commission will continue to engage the government on the urgent need for reparations to victims,” the Commission told Justice Info. “Additionally, we will engage with international partners to support other aspects of our work including the implementation of psychosocial support, medical support and empowerment for victims.”

Remaining obstacles to justice

For the survivors of the November 11, 1994 counter-coup – seven men who fought against poor barracks conditions and unfulfilled promises were met with summary execution – the reparation payment is seen as a positive show of government commitment, but it does not substitute the desire for criminal justice. “People accused of coups should face a court, not arbitrary execution. The murderers have confessed. They should be prosecuted... soonest,” said Dawda Darboe, brother of the late Momodou Lamin Darboe, one of the soldiers who were executed in Yundum Barrack, a military encampment about 35 minutes drive from Banjul.

While the Commission processes cheques, it cannot erase the geographical reality of the victims. Abdoulie J. Darboe lives a chilling fact of post-Jammeh Gambia where survivors and perpetrators often live and work side-by-side. “Njie Ponkal [real name Babucarr Njie] is my neighbor,” Darboe reveals, referring to a former orderly to Sanna Sabally, N°2 of the military junta in 1994, allegedly implicated in the November 11 executions. “We are together, pray at the same mosque, and meet on the street daily.” But there is also an apparent lack of administrative justice where alleged perpetrators like Zakaria Darboe – also named in the same incident – are holding high-ranking roles such as Immigration Commissioner in Upper River Region, the most western of the country’s five divisions. Abdoulie Darboe said such issues remain the biggest hurdle to closure.

The victims of November-11 also still await the proper burial of the remains of their relatives. For eight years, the bones of those killed more than 31 years ago have sat in a mortuary in Banjul, awaiting forensic identification. “A Muslim is entitled to a proper religious burial,” Mamudu Sillah pleads. Families are now asking the government to hand over the remains, even if they cannot be individually identified, so they can be laid to rest in a mass grave where families at least know where their loved ones lie.