In April 2019, the Gambia´s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) embarked on a much-publicized excavation and exhumation at the Yundum Barracks, the country’s biggest military encampment over an hour drive from Banjul, the capital city. Relying on witness testimonies and eye-witnesses, the team of investigators found seven bodies. They are believed to be among at least eleven soldiers executed on November 11, 1994, after an attempted counter-coup against the head of a military junta led by Yahya Jammeh, who had come to power on July 22.

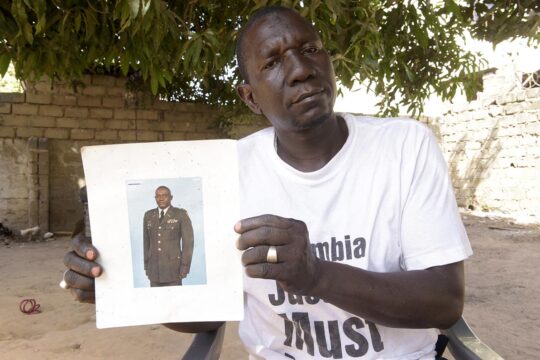

For more than four years the remains have been in storage at the Edward Francis Small Teaching Hospital in Banjul. Their identities are still unknown as no DNA testing has been conducted. “The exhumation of our loved ones for 4 years without being identified, so that they can return to their families, to be given a befitting burial, has serious negative impact on me and my family as Muslims,” said Mamudou M. Sillah. “When we contact the government, there is only one answer: we do not have the required tools to carry out the DNA [test].”

“Take no prisoners”

Sillah is the brother of Cadet Amadou Sillah, a soldier in the Gambia National Army who on November 10, 1994, left his home to resume his duties at Yundum Barracks. The following day, he was arrested, tied with a cable and transferred in a military Land Rover to the Firing Range in Brikama, where he was summarily executed. He was eventually taken back to Yundum Barracks and secretly buried, according to the TRRC´s findings.

“We also heard that experts would come from Europe to identify the remains and hand them over to their families. But that was the last thing we heard about this issue. We know nothing because nobody tells us anything. Since the bodies were exhumed from Yundum, no information,” added Awa Njie, widow of Abdoulie “Dot” Faal. The TRRC found that her husband was the first killed among the slain soldiers. After his arrest on orders of Edward Singhateh and Sanna Sabally, top members of of Jammeh’s junta, Fall and others were subjected to torture and taken to the remand wing of Mile 2 Central Prison, where they were further tortured. They were then transported to Yundum Barracks. After Faal’s execution, his body was thrown into a pit, the TRRC was told.

In their testimonies before the Commission, both Singhateh and Sabally said the directive from Jammeh was to “take no prisoners,” meaning the soldiers had to be killed. Sabally described the incident as a war with “enemies, not captured soldiers to be treated humanely.”

“We haven’t got the expertise”

Following the exhumations, a year later the TRRC assured that the identification process was “underway”. But in 2023 it is yet to start.

“When it comes to identification,” explained to Justice Info Thomas Gomez, chief superintendent of Police and local forensic scientist who led the exhumation team in 2019, “it’s not as easy as people think. There are so many things involved. The condition of the remains is one thing and the finances involved is another. We haven't got the expertise to move things from where they are now. We are dealing with degraded remains that have been in the soil for about twenty-five years.”

The DNA test cannot be conducted in The Gambia, he admitted. And until it is done the remains would continue to be housed at the mortuary. According to a 2022 article by experts from NGO Justice Rapid Response, this situation “could negatively affect evidentiary value.” The Gambia’s Truth Commission, it reads, “faced significant capacity challenges in searching for the disappeared particularly around forensics. […] Following its investigative priorities, the [Truth Commission] proceeded with the exhumations [at the Yundum barracks] without the required technical knowledge on-site and with limited preparation and participation of victims' families. It had no comprehensive plans to conduct post-exhumation forensic analysis of the remains.”

Describing the conditions the remains are kept in, Gomez was not reassuring: “For three years I have not been there to check on the remains. Maybe the roof is leaking. Maybe they moved from fans to AC now. If the condition remains good in that store, then that will be fine. And I hope they remain fine because there is a mortuary.”

Plans for more exhumations?

According to its 2020 interim report, the TRRC discovered up to five suspected burial sites, estimating that it could find at least a hundred disappeared persons. The Commission planned to search for, recover, identify and return these bodies to their families. No exhumation, however, has been conducted since 2019.

Justice Info contacted the former executive secretary of the Truth Commission, Baba Galleh Jallow, who suggested that we contact the Ministry of Justice as “the remains were handed over to them with recommendations to do the needful concerning them.” Last month, two experts from the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team and one jurist from the University of Chicago Law School Global Human Rights Clinic came in The Gambia at the invitation of the African Network against Extrajudicial Killings and Enforced Disappearances (ANEKED), an NGO which proposed assistance to the Gambia Ministry of Justice. “Obviously, there is a tremendous urgency in need for comprehensive, rigorous, credible investigations both to give answers to the families and justice. There is a general lack of expertise in terms of technical forensic investigations, police investigations, and how you actually carry out the search for graves’ recovery and analysis, exhumation, and how at the level of doctors you carry out autopsies and forensic anthropological analysis at the lab level,” said the human rights advocate and lawyer from the University of Chicago Anjli Parrin to Justice Info after a four-day mission.

And soon it will be 30 years

In a June 20th press release, ANEKED and the Justice Ministry hoped “that the outcome of the mission will close capacity gaps […] to kick-start the search and identification of the remaining scores of victims of human rights violations identified by the [Truth Commission] that are still missing.”

For Gomez, even with the required expertise, there are uncertainties surrounding the identification process. “I am not 100% positive to say yes they will be able to identify all of them because I know the condition [of the remains]. It is a 50/50 thing. It is possible you might not, it is possible you might.”

Following the Truth commission’s recommendations, prosecutions of the top leaders of Jammeh’s military junta – including Jammeh, Singhateh, Sabally and senior military officers who allegedly participated in the November 11, 1994, tortures and killings – are now expected to commence early 2025, according to the recently disclosed government´s implementation plan. Towards the end of the year, the government said it plans to establish “a mechanism for the exhumation and identification of disappeared persons.” By the time it may bring results it will be 30 years since the killings took place.