Albin Stanislavovych Havdzynskyi was born in 1923 in the village of Bobryk Pershyi, Liubashivsky district, Odesa region. When he was five years old, his family was deprived of their property and forced to move to Odesa, where he lived his entire life. There he established himself as an artist and later became a renowned Ukrainian landscape painter and specialist in genre and portrait painting.

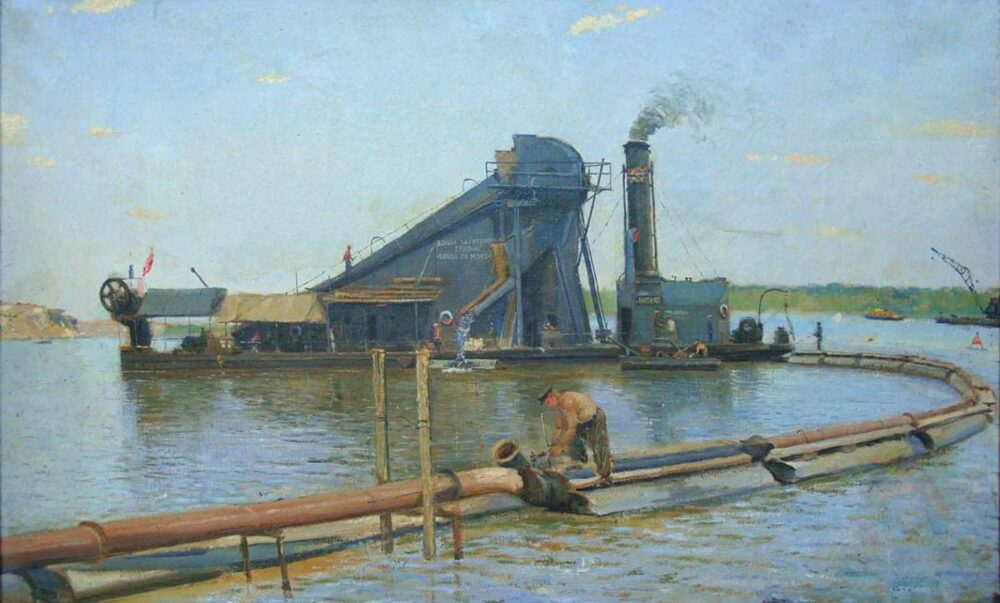

In 1950, after graduating from the Odesa Art School, Havdzynskyi travelled to the construction site of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant. There, he created a series of works dedicated to the construction of the power plant, but also recreated on canvas the destruction of Velykyi Luh, the spiritual capital of the Zaporizhzhia Sich, a semi-autonomous state of Cossacks in the 16th-18th century.

The construction of the Kakhovka power plant lasted from 1950 to 1955 as part of the ‘Great Communist Construction’ project, designed to implement Stalin’s ambitious ‘Great Plan for Nature Transformation’ initiative. The project included large-scale hydroelectric power plants, irrigation systems, and navigable canals, but it came at the cost of flooding lands of unique historical value.

In 1961, Havdzynskyi was awarded the title of Honorary Citizen of the new city of Nova Kakhovka. An art gallery was founded on 4 November 1967 as the art department of the Kherson Local Lore Museum. The artist donated all 300 of his paintings to the city of Nova Kakhovka, and they became the core of the new art gallery that was eventually named after him in 2003 while he was still alive.

However, during the Russian occupation of Nova Kakhovka in 2022, the art gallery was looted, and the works of artists that had been preserved there for decades were taken away by the Russians to an unknown location.

The work of his life

Syla Hromad’s editorial team met with the artist’s granddaughter, Linda Strautman, an art historian who founded a small gallery in the centre of Odesa, where she keeps some of her grandfather’s works, a self-portrait and archive photos. She described her grandfather as a man whose life and work capture the historical tragedies of the Ukrainian people during the Soviet regime.

Havdzynskyi’s first drawing was published before WWII in a Soviet magazine when he was 15 years old. But he dedicated most of his paintings to the so-called ‘construction of the century’: the building of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant. In a way, he became a record keeper of this construction, documenting every stage of its development. “In the early 1960s, there was no colour photography, so the construction of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant can only be seen in Havdzynskyi’s paintings: machines, pipes which, interestingly, were already rusty when they were installed and were painted later. He captured this fact on canvas,” Strautman recounts.

In fact, Havdzynskyi arrived at the construction site of the power plant before it was even built, in the 1940s. At that time, there was a village called Kliuchove, so he began to depict the area even before the construction began. “His first paintings date back to 1949, when the first wooden houses for party leaders and barracks for workers were under construction. That is how the town of Nova Kakhovka was founded,” Strautman says.

According to historians, the Soviet regime never took into account human losses. People were forced to work either for free or for a small wage. Strautman recalls that, according to Havdzynskyi’s stories, among the builders of the power plant were German prisoners of war and political prisoners who had been forcibly brought to the Kherson region. Many of them, unable to withstand the workload, poor conditions and hunger, allegedly died during construction. Strautman says that her grandfather would only whisper about this because he was “afraid of Stalin” until the end of his life. “There were incidents when people fell into the dam during construction, but no one searched for them afterwards, so human bones continued to be found on local beaches up until recently,” she says. “That was the high price of construction, which many people knew about but remained silent.”

“In 2003, the collection of artworks was expanded when my grandfather donated another 63 paintings to the museum. The pieces were from different periods and depicted landscapes of Poland, Great Britain, and Germany. Other additions to the collection were works brought in by local residents, who had preserved his early sketches. I don’t know any other artist who had an art gallery named after him during his lifetime. He was very touched by that,”the artist’s granddaughter recalls.

The looting

Strautman is critical to the management of the gallery before the Russian invasion. “Most of [Havdzynskyi’s] paintings were kept in storage. When we would visit Nova Kakhovka, we would see 20-30 works framed on the walls, while all the others, about 200 small-format paintings, were kept separately. They were stored, overlaid with paper, some with cardboard, canvas; and among them were unique miniatures, quite small in size, but depicting the city, the Dnipro River, and everything that was being built. Any museum in any country in the world would envy such paintings,” Strautman says.

From the very first days of the full-scale war [in February 2022], Nova Kakhovka fell under Russian occupation. The Havdzynskyi Art Gallery remained intact during the shelling of the Kherson region, but it stopped working. Then on 1 November 2022 the Russians looted the collection of paintings and took the exhibits to an unknown location, as reported by the City Council. Witnesses told Strautman that the occupiers took all the exhibits without any regard for their preservation or integrity. “They didn’t even wrap them, they just threw them onto the back of a truck, as people told me. Even the slightest touch could tear or puncture the canvases, but no one cared, they just took everything away.”

After Kherson was liberated in June 2023, the Russians blew up the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant to disrupt the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ offensive, thereby destroying the dam. Almost 70 years after the construction of the power plant, the story of Ukrainian villages being flooded repeated itself. The artist’s granddaughter is convinced that if the gallery’s collection had remained in Nova Kakhovka, it would not have escaped the destruction caused by the floodwaters.

Havdzynskyi’s paintings resurfacing in Moscow

In 2024, Havdzynskyi’s paintings suddenly reappeared in Moscow, at an exhibition in the Transneft office, Russia’s state-controlled oil pipeline company. It was reported by the Centre for Investigative Journalism. Among the people in the photo, the journalists recognised Volodymyr Bodelan, the son of party leader and former mayor of Odesa Ruslan Bodelan, who fled Ukraine back in 2014. (In 2016, Ukrainian authorities issued a warrant for Bodelan’s arrest on suspicion of negligent performance of his duties, resulting in people’s deaths.) Bodelan Jr. was now a representative of the occupation administration of the Kherson left bank region, standing side by side with the so-called ‘Gauleiter’ Volodymyr Saldo, and bragging about the stolen relics from the occupied Ukrainian lands. The creator of the paintings was now referred to as a “Soviet artist”. The occupiers made no reference in the TASS news report to the fact that the paintings exhibited in Russia belonged to the Albin Havdzynskyi Art Gallery in Nova Kakhovka.

“I recognised his works, of course! There were self-portraits of my grandfather, and not only works from Kakhovka, but also those he donated to the museum later, in 2003 – landscapes he created in Poland, Germany and Kyiv. We thought they had already been sold on the black market,” Strautman says.

From the very beginning of the Kherson region invasion, the occupation administration of the Kherson region’s left bank established its representation in the Russian capital. “The occupiers appointed collaborator Volodymyr Ruslanovych Bodelan as the institution’s leader,”Ukrainian media reported. Bodelan was appointed deputy to the so-called ‘governor’ Volodymyr Saldo.

In 2025, a Ukrainian court sentenced Bodelan Jr. (in absentia) to 10 years in prison for collaboration.

The cultural battlefront

The theft of Havdzynskyi’s works and other exhibits, considered cultural treasures of Ukraine, by Russia is being investigated by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) and the Kherson Regional Prosecutor’s Office. The authorities have officially initiated criminal proceedings on 31 December 2022 on the grounds of a criminal offence under Article 342 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine regarding the theft of cultural property.

“At the beginning of the Russian invasion and occupation of Nova Kakhovka, the museum’s collection amounted to 1,176 exhibits, including works from the main collection (1,034 fine art pieces, 65 decorative and applied art pieces, and 77 photographs). There were 57 pieces in the scientific and auxiliary collection. The gallery’s art collection included 297 paintings and graphic works by A.S. Havdzynskyi, 237 of which he donated to the city in 1961; a collection of etchings by People’s Artist of Ukraine V.F. Myronenko, a collection of illustrations by People’s Artist of Ukraine V.G. Lytvynenko, and others,” the prosecutor’s wrote to Syla Hromad. “The facts of the mass expropriation of art collections from the gallery – paintings, drawings, sculptures – and the display of stolen paintings have been duly acknowledged.” According to the Kherson Prosecutor’s Office, “open sources, including those of the aggressor country, are being monitored in order to uncover evidence of paintings being sold on the black market.” The possible involvement of Volodymyr Bodelan, who displayed the stolen Havdzynskyi’s paintings in the Transneft office in Moscow, is also being investigated.

In addition, the Main Intelligence Directorate’s (HUR) confirmed to Syla Hromad that information about Havdzynskyi’s stolen paintings had already been registered in the ‘Stolen Heritage’ section of the War&Sanctions web portal. “The published information relates to four works by the People’s Artist of Ukraine A.S. Havdzynskyi, stolen by the occupiers from the gallery in November 2022 and exhibited in November 2024 at the exhibition ‘Always New Kakhovka’ at the Transneft main office (Moscow),” they wrote. However, to properly review and disclose the information in the ‘Stolen Heritage’ section of the War&Sanctions web portal, HUR says they” need a precise list and photographs of all the paintings mentioned in the request, as well as information about the individuals involved in their removal (in particular, supporting evidence), which is currently absent”.

The only person who has a complete list of Havdzynskyi’s stolen works with photographs is the artist’s granddaughter, Linda Strautman. According to her, representatives of the Kherson Regional Prosecutor’s Office contacted her a year ago with a request to provide materials for the investigation, but nothing has been done so far. According to the artist’s descendant, the investigation is progressing slowly. [The full conversation with Albin Havdzynskyi’s granddaughter is available for viewing in the video from Syla Hromad.]

“They stole a part of our soul”

“Our city was founded on the site of the former village of Kliuchove, derived from the word ‘kliuch,’ meaning ‘source.’ That is why it is often called ‘the city of a thousand sources.’ There are 900 natural sources gushing from the ground. On 28 February 1952, the Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union changed the name to Nova Kakhovka,” the mayor of Nova KakhovkaVolodymyr Kovalenko recalls. “The art gallery was the heart of the city. It had a nationwide renown. Enerhodar, Mykolaiv, Kherson: everyone would ask for Havdzynskyi’s exhibitions. Until the last day of the artist’s life, we would visit him with delegations, support him, and his works became part of Ukraine’s cultural heritage,” he says.

Just before the invasion, the city had a population of 56,000 and local authorities were preparing to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the city’s foundation. According to Kovalenko, the enemy army entered the city on the first day of the full-scale invasion, 24 February 2022.

“We faced the occupation without insulin, without bread, without the most basic necessities. But the people stood firm. Only a few of our educators, doctors and cultural workers agreed to collaborate with the occupiers. We acted with dignity,” he says. According to him, on the third day the occupiers denied art gallery employees access to their workplace. The building was immediately placed under armed guard and the keys were confiscated. “They stole a part of our soul. They stole the memory of the generations who built this city. But they cannot destroy what is inside us – our dignity, our love for Nova Kakhovka and our faith to get it back,” he added.

1,7 million items of cultural heritage stolen

The theft of the Havdzynskyi Art Gallery in Nova Kakhovka was not a coincidence or a ‘side effect’ of the war. As reported by Minister of Culture and Strategic Communications Mykola Tochytskyi, “Russia has stolen 1.7 million items of cultural heritage from the temporarily occupied territories: from archaeological objects to museum collections, which the Russian Federation has appropriated in violation of all norms of international law.”

According to the mayor, not only military but also Russian officials were involved in the looting. He also said that Ukraine imposed sanctions against Russian cultural professionals, museum workers, and other officials. “We are talking about 55 individuals and three institutions whose involvement in the theft, destruction and annihilation of Ukrainian cultural heritage has been established,” specified Tochytskyi.

According to the Main Intelligence Directorate, Russia is seeking to erase Ukrainian national identity and legitimise its aggression and occupation by appropriating Ukrainian culture and history. On 8 October 2025, the HUR published data on 178 items stolen by Russians in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine in the ‘Stolen Heritage’ section of the War&Sanctions web portal. Among them are works by Albin Havdzynskyi, stolen by Russians in Nova Kakhovka. “Documenting crimes is the first step towards establishing justice and prosecuting all those involved,” HUR’s statement says.

This report was produced thanks to a grant by Fondation Hirondelle/Justice Info. A full version of this article was published on November 29, 2025, in "Syla Hromad".