This has been an eventful week showing the important role transitional justice can play in places like Cambodia, Kosovo, Kenya and Burundi, but that a hesitant international community often sets it in motion late.

On Friday, the Dutch government announced that the European Union is to set up a special court in The Hague to try suspected war crimes committed by UCK separatist rebels during the Kosovo war of 1998-1999. This confirms a previous report published by JusticeInfo.net. The tribunal will be governed by the law of Kosovo but composed of international judges and based outside the country, for fear that the accused, considered by some to be national heroes and now in charge of this former Serbian province, could threaten and intimidate witnesses and judges. Pristina has been under pressure to set up such a tribunal ever since the Council of Europe published a report in 2011 on suspected crimes perpetrated on 500 Serb and Rom prisoners by UCK members during the war.

This “Marty report” (named after a former Swiss prosecutor who is a member of Fondation Hirondelle’s board) found evidence of summary executions and trafficking of organs taken from murdered victims. It pointed to the implication of former UCK leader and current Foreign Affairs Minister of Kosovo Hashim Thaçi, accusations which Thaçi has denied.

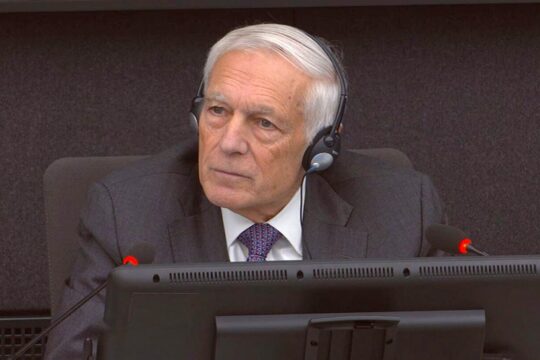

Another example of tardy justice is the second trial before a UN-backed court of two former aides of Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot for suspected genocide perpetrated on Vietnamese and the minority Muslim Cham community between 1975 and 1979. Between 100,000 and 500,000 Chams (out of a total of some 700,000) were killed by the Pol Pot regime, which is held responsible for the deaths of two million people. The regime’s ideologue Nuon Chea, 89, and the former “Democratic Kampuchea” head of State Khieu Samphan, 84, have been appearing in this trial since 2011. They were previously convicted of crimes against humanity in another trial before the same court. In the current trial survivor Math Sor, a Cham woman who was an adolescent at the time, told the Court on Wednesday how Khmer Rouge officials arrived in her village, detained and bound some 30 women and then carried some of them off.

“I heard them crying ‘Please don’t rape me!’” she told the Court. She also said she had through a crack in the wall seen soldiers decapitating women.

Transitional justice is also following its slow path before the International Criminal Court (ICC), which this week examined a request to acquit Kenyan Deputy President William Ruto and radio presenter Joshua Arap Sang, accused of crimes against humanity committed during post-election violence in 2007-2008. The ICC judges are expected to hand down a decision in the coming weeks on this symbolic case for Africa. Kenya, supported by the African Union, accuses the ICC of only going after Africans. In December 2014, the Prosecution already dropped charges for lack of evidence against Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, former political rival turned ally of Ruto.

The lessons of the past are not enough to stop the crimes of the present. A leaked UN memo revealed by the press this week recognizes that the UN does not have enough means to protect civilians if the worst, i.e. a genocide, is unleashed in Burundi. As if the United Nations were trying to cover itself in advance.

Another warning from the UN also came on Syria, which has been abandoned by the international community. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon warned that the siege of starving villages like Madaya by the Bashar al-Assad regime and armed opposition was a war crime. The UN Security Council has the power to refer war crimes in Syria to the ICC. But Russia and China, which are protecting the Syrian regime, would veto such an initiative.