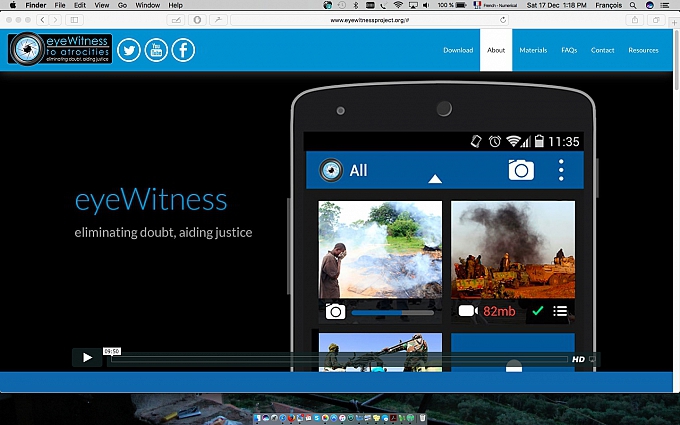

Can a smartphone and an App hold war criminals accountable? Eyewitness, an App developed by the International Bar Association (IBA), is trying to help combat impunity with this new technological tool, said to be reliable, free and accurate.

The aim is to document suspected war crimes witnessed by victims or others, through photos and videos. Wendy Bett, director of eyeWitness, explained in an interview with JusticeInfo the advantages of this project. “Images taken with the eyeWitness app include a verifiable GPS time, date and location,” she says. “All come from a registered instance of the app. Each image includes a unique numeric code which can be checked to show that the image has not been altered. Users can safely store an original copy of each image in the eyeWitness secure server hosted by LexisNexis. This acts as an offline evidence locker and protects the chain of custody required in criminal cases.”

This is hi-tech and respect for criminal procedures in the service of the law.

This week, several countries have shown their difficulties in conducting rigorous procedures. One example is Burkina Faso, where people are still waiting for justice, notably in the symbolic cases of murdered journalist Norbert Zongo and former president Thomas Sankara. In the cases of both these assassinations the main suspect, according to investigations and the word on the street, is the last ex-president, Blaise Compaoré. “It remains to be seen how far the new authorities will push the case, given that some of them have links with the Compaoré regime,” writes Gaël Cogné, JusticeInfo’s correspondent in Ouagadougou. “The NGO International Crisis Group (ICG) warned in a report in early 2016 that `impunity and injustice, if they persist, could quickly push the people of Burkina Faso to take to the streets again`. And, it adds, `since the new authorities sprang from the old regime, some judicial cases that could compromise the new government may never reach a conclusion`.”

In Mali too, the start of trial at the end of November of Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo, leader of the 2012 coup accused of murdering 21 soldiers opposed to his action, has raised hopes of justice in the country. “For too long in Mali, men like Sanogo have been seen as untouchable and above the rule of law,” writes Mamadou Ben Chérif Diabaté, JusticeInfo`s correspondent in Bamako. “Malians, who are already engaged in a difficult reconciliation process, are hoping the Sanogo trial will be just the start of fighting impunity through impartial and independent justice, whatever the nature of the crimes, or the identity of the suspects, the region or context in which they were committed.”

This shows the fundamental importance of transitional justice processes in countries experiencing difficult transitions.

Tunisia is meanwhile continuing public hearings of victims before the country’s Truth and Dignity Commission. “These hearings represent a key moment for rebuilding the collective memory at a time of transition,” transitional justice expert Kora Andrieu told JusticeInfo’s Tunisia correspondent Olfa Belhassine. “This is a pause, a solemn moment, almost a ritual, in which we can listen and look inside ourselves, both on an individual and national level,” she says. “Tunisia is not an exception. In most contexts, setting up a Truth Commission is a painful, dangerous risk, which can upset and sometimes divide people, at least in the short term. Not everyone wants to hear the truth. The subjective prisms through which each person sees reality often go very deep, and their divides sometimes seem insurmountable. The role of the Truth Commission is precisely to recognize this diversity of views and opinions without trying to impose a single view of the past, and to leave the work of interpretation to researchers and historians.”

Can this issue of how people see the past and how they come to terms with it ever find a resolution when the crimes in question are genocide and crimes against humanity? This question is raised after the early release of two Rwandan genocide convicts, sentenced to 30 and 23 years respectively by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) for their role in the 1994 genocide. Ferdinand Nahimana, one of the founders of hate-radio Radio-télévision libre des mille collines (RTLM), and Father Emmanuel Rukundo, a former military pastor convicted of aiding and abetting the massacre of Tutsis who sought refuge at religious sites, will be free in 2017. The presiding judge based his decision on the practices of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), according to which convicts are eligible for release when they have served two-thirds of their sentence. But these early releases are criticized in Rwanda, where some see them as minimizing the 1994 genocide.