Is the concept of universal jurisdiction, in which Spanish judges used to lead the way, about to come back in Spain? A Bill to this effect is in the parliamentary works, even if it is blocked for the moment by the party in power, the Popular Party.

Some voices within Podemos, the third largest political force in the lower house of parliament, have in recent weeks been demanding that Spain become once again a country where justice has “no limits and no borders”. This was the recent call of Miguel Urban, one of the co-founders of Podemos, on Publico-TV. In April, renowned Spanish jurist Carlos Castresana expressed regret that “with regard to universal jurisdiction our country is now completely out of the game”. Castresana is former president of the association of progressive prosecutors (UPF) and had a UN mandate from 2007 to 2010 leading the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala.

In 2014, defenders of universal jurisdiction, including groups working on “universal” causes (Tibet, Argentine dictatorship, Western Sahara, etc.) were devastated when conservatives of the Popular Party used their absolute majority in parliament to push through an “express reform” reversing universal jurisdiction law. Five years earlier in 2009, Socialist José Luis Zapatero had already made the law more restrictive, saying that crimes prosecuted must have a link with Spain. And so in 2014, the conservatives went further, depriving judges of the National Audience (the main national jurisdiction for international crimes) of their power to prosecute suspects from anywhere in the world unless they have Spanish citizenship. This move was because of diplomatic headaches caused by international jurisdiction cases, notably with regard to Israel and China. Israel had been accused of committing a crime against humanity on May 31, 2010 when it attacked the “freedom flotilla” (38 injured, 9 dead) which was trying to break the blockade on Gaza. As for China, there were several allegations (genocide, torture, crimes against humanity) linked to repression in Tibet, including against former president Jiang Zemin.

Diplomatic headaches

Mariano Rajoy, who has been Spanish Prime Minister since the end of 2011, had thought that these diplomatic “headaches” were a thing of the past. But at the end of last year, he won only a slim election victory. His party certainly got more seats than the Socialists and the radical left Podemos, but he now has to run a minority government, exposed to joint initiatives from the opposition. This is what happened in February 2017 when the separatist Catalan party ERC – which is in open war against the Popular Party – proposed to reverse the PP’s “amputation” of universal jurisdiction law and reform it so as to “return to the pre-2014 situation”. This proposal was passed with 176 votes in favour and 136 against. Since February, the party in power has managed to keep getting this move for legislative change postponed. We do not currently know when it may be brought up for further discussion.

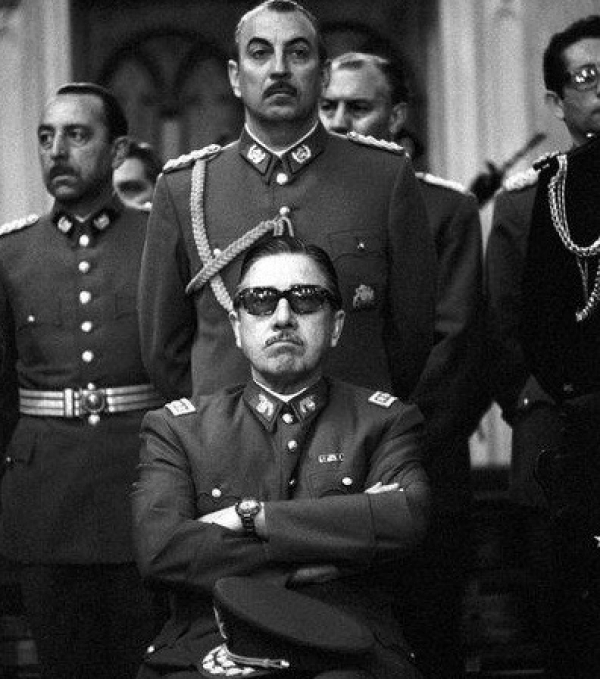

Nevertheless, it has revived the hopes of those nostalgic for the time when Spain had universal jurisdiction legislation under which, for example, former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998 and Argentine torturers Adolfo Scilingo and Ricardo Cavallo were extradited to be tried in Madrid. “If this reform is passed, Spain could once again be a leading light for justice,” says Alan Cantos, president of the support committee for victims of repression in Tibet. “Our shame will be lessened if the principle of universal jurisdiction is restored.” Leaders of the Popular Party have not made any official statements on the issue. But unofficially, some say restoring the previous legislation would bring new diplomatic tensions, for example with the United States in the case of José Couso, a Spanish photographer killed by the US army during the Iraq invasion in April 2003. In July 2010, National Audience judge Santiago Pedraz launched in vain an international arrest warrant against three American soldiers, after indicting them. If the legislation were to be changed, the complaint filed by the Couso family would be reactivated.