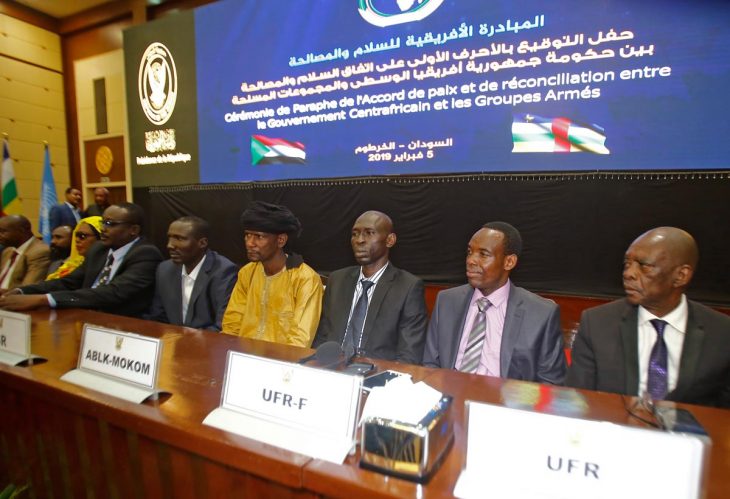

JUSTICEINFO.NET: The new peace agreement – the fourteenth in twelve years – ignores the very existence of the Special Criminal Court (SCC) and avoids talking about criminal prosecution. What does that mean?

IGOR ACKO: This silence is, from the point of view of the population, directed against them. There was a need to bring the armed groups on board, although when you go through the agreement, you don't really see what it gives to the rebels, who are strong on the ground. To appease the population, the agreement acknowledges in its preamble that impunity has sustained the cycle of violence. But the agreement does not go all the way. They're just words.

How should we interpret the the Minister of Justice's absence this weekend at the launch of a major tour on the SCC, despite the fact that his presence ha been announced

I believe that, for the time being, it is not in the government's interest to prosecute rebel groups. When you read the Khartoum agreement, you realize that transitional security arrangements extend over a two-year period until the next elections. In entering into this agreement, the government is thinking about the election deadlines, with a view to staying in power. It knows that rebel groups must be spared until then. The government is playing a balancing act and trying to satisfy the rebels in order to make progress in the country's governance. It is betting on improved security for the next presidential campaign. But there again, it is not clear, as you cannot see what is being given to the rebels in return.

I think justice for them can wait. Perhaps the SCC will deal with violence among civilians until members of armed groups can be prosecuted.

Is it really possible to support both the SCC and the peace agreements?

No, it's quite contradictory. But this contradiction dates back at least to 2015. If the Khartoum agreement is not popular with Central African citizens, the main reason is that the problem of the rebels was not resolved during the transition. The transition was completed and elections held with the rebels still active. In other countries – for example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with its four vice-presidents appointed in 2005 – a political arrangement had been reached to put an end to the rebellion problem. In the Central African Republic, at the Bangui Forum [in 2015], the population was involved and what the participants called the "republican pact", integrated into the Constitution, emerged. Without addressing the problem of armed groups, the new foundations of society were laid. However, the Khartoum agreement runs counter to this pact, with, for example, the participation of armed groups in the government, considered a reward for violence. It's very unpopular.

After this agreement, does CAR not have, with a truth commission, a demobilization and reintegration program for combatants, a mixed court, the possibility of recourse to the International Criminal Court, all the tools of transitional justice?

Yes, but what are the conditions for their implementation? Will the rebels lay down their arms and go to court? I don't think so. The agreement mentions the possibility of a presidential pardon. Here too, it is a tool that can be used to manoeuvre with regard to certain influential leaders, electoral or other calculations. Under the agreement, as long as transitional security measures are implemented – including the training of armed groups to form joint patrols with the Central African Armed Forces – the leaders cannot be brought to justice. We negotiated a peace for the benefit of the government and not for the benefit of the justice that the people are demanding.

Should we expect a reaction from the population or civil society?

Since the agreement reiterates the principle of fighting impunity -- although remaining vague -- it does not allow civil society to take action. If the agreement had it would "stop the SCC for two years", they could have organized the response. It's a smart agreement.

In 2018, lots of things happened on the justice front in CAR: national courts conducted several trials, two former anti-Balaka were arrested by the ICC and the SCC announced the opening of its investigations. In your opinion, what do Central Africans think?

The public greatly appreciated the criminal hearings [in the ordinary courts]. People appreciated the fact that there were trials on both sides, of people like Andjilo [Rodrigue Ngaïbona, aka General Andjilo, former anti-Balaka leader, sentenced on 22 January 2018 to life imprisonment] and of some former Seleka [coalition in power in 2013, which the anti-Balaka opposed]. Things have been fairly balanced. With the ICC, people agree with the arrests, but they want them to be as balanced as with the ordinary courts. For the SCC, people are still waiting to see the trials to form a positive or negative opinion. But one thing is for certain: people really expect justice in the Central African Republic, they have said it over and over again.

If the truth commission, already announced at the Bangui Forum in 2015 and provided for in the Sant'Egidio agreements in 2017, is effectively implemented, could it work?

I believe that it can work at the local level. When communities that have experienced tensions sit down to talk, people will understand each other, they will get on with their lives. But for mass crimes, I don't think it's really going to work. Since we are talking about reparations, people may be able to rebuild churches, rebuild mosques, try to help former members of armed groups reintegrate into communities. This has been tested by several NGOs and has worked at the local level. But not with the armed leaders. And there are crimes that will be difficult to deal with, such as the destruction of entire villages by Seleka or anti-Balaka.