The summer of 2018 visited a naturalized Ethiopian American with a twinge of pity. After about 40 years of anonymity, Nigussie Mergia, who is now 58 years old, could be facing a fatal intersection of time and space following his arrest on charges of multiple immigration offenses. The sealed indictment from the United States Department of Justice (DoJ) alleges that Mr. Nigussie lied in his immigration documents about his role in persecuting Ethiopian prisoners for their political opinions during the country’s so-called “Red Terror” period in 1977-78. His trial is to open on February 25 before a district court in Virginia.

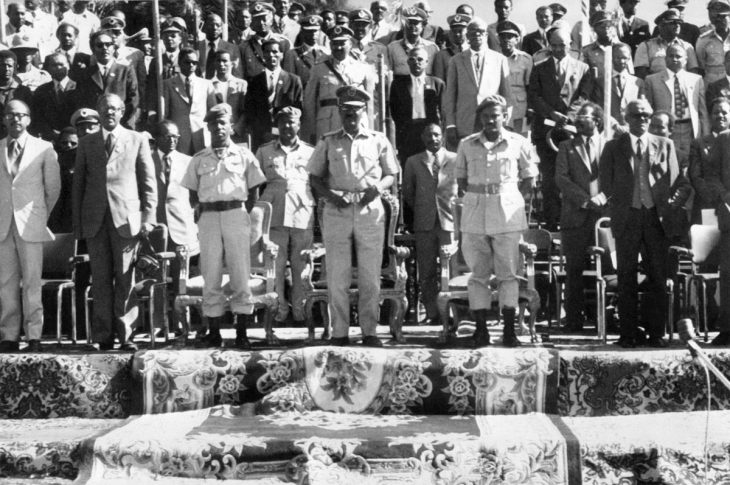

Mengistu and the Red Terror

“Red Terror” was a brutal and violent political phenomenon in 1977-1978 in Ethiopia, an unbridled moment of extra-judicial mass execution, torture, and arbitrary imprisonment perpetrated by the military government of socialist Ethiopia, known as the Dergue, against its political opponents.

The Dergue ruled the country for 17 years, from 1974 to 1991. In March 1977, three years after the Dergue’s assumption of power, President Mengistu Hailemariam smashed bottles filled with red fluid (representing the blood of enemies) before a huge crowd at Addis Ababa’s Meskel Square, expressly proclaiming a state of “Red Terror” (Qey Shibir in Amharic) against his political opponents. In the following two years thousands of students, young men and women would turn up dead in the streets of the capital and other cities. In an elaborate theatrics of violence, the government authorities would not allow the victims' families to take their corpse without first paying for the bullets used to kill them.

This violent campaign claimed the lives of an estimated 40,000-100,000 people. A Human Rights Watch report characterized it as "one of the most systematic uses of mass murder by the state ever witnessed in Africa.”

The Red-Terror Trial

The Dergue regime was toppled in 1991. The new government established the Special Prosecutor’s Office (SPO) in 1992 to “investigate and prosecute” former officials of the Dergue. It came to be known as the Red-Terror Trial and is sometimes referred to as the African Nuremberg, although it is the least known and least researched post-atrocity justice effort in contemporary Africa. The first indictment was filed in 1994. According to Human Rights Watch data, 5198 individuals were indicted on charges of killing 8752 people, causing the disappearance of 2611 others, and torturing 1837. Of all individuals indicted, 2,246 were already in detention and 2,952 were charged in absentia.

The defendants were classified into three main categories: policy and decision makers; officials who passed on orders or reached decisions on their own; and those directly responsible for committing the alleged crimes. In the first category were 55 top officials, including Mengistu, ministers, military commanders, and others. The charges brought against this group included genocide and crimes against humanity, torture, murder, unlawful detention, rape, forced disappearances and abuse of power. On 12 December 2006, the Ethiopian Federal High Court convicted all but one of these top defendants. Others from different categories were also convicted in various federal and regional courts.

The Red-Terror Trial wasn’t immune to criticism. The duty to preside over such a complicated and demanding trial fell to junior and inexperienced judges; senior judges were dismissed for having ties to the Dergue regime, and some of the new judges, especially in the regional courts, were either trained for a very short time or without any training in law or court experience. The lack of an institutionalized and skilled public defender system in the country had a negative impact on the rights of the defendants. The quantity of evidence proved to be an additional problem for the prosecution. An attempt to computerize the prosecution evidence foundered when the American computer operatives were expelled on suspicion of espionage.

Despite the pitfalls, the Red Terror trial remains significant and represents a trail-blazer for national accountability and post-atrocity justice in Africa.

Revolution squads

During the period of Red Terror, the Dergue regime divided Ethiopia's capital, Addis Ababa, into about twenty-five administrative units or wards. A ward was called a Higher Zone (Kefitegna in Amharic). It also organized volunteer civilians known as "Defense of the Revolution Squads" and distributed arms and ammunitions to them. The squads carried out the campaign by detaining, interrogating and torturing the opponents at each higher zone or ward.

Nigussie Mergia came to America in 1999. He obtained U.S. citizenship in 2008. His case has been investigated by the Homeland Security Investigation unit with the support of the Human Rights Violators and War Crimes Center, whose goal is to “prevent the United States from becoming a safe haven to those individuals who engage in the commission of war crimes, genocide, torture and other forms of serious human rights abuses from conflicts around the globe.”

According to the U.S. DoJ’s indictment, filed before the Federal District Court for Eastern District of Virginia in August 2018, a young Nigussie had served as a civilian interrogator in the Higher Zone Number 3 prison (kefitegna 3) around 1977-1978. U.S. prosecutors produced a two-page ledger, which carries Nigussie’s name. Apparently, the document emanates from an Ethiopian court. Prosecutors allege that the defendant was an agent of the Dergue and in that capacity he had persecuted and interrogated political opponents at the Higher Zone 3 prison. However, prosecutors seek to pursue Nigussie’s alleged violent past only from the angle of an immigration offense in connection to his misrepresentation in gaining entry to this country and, ultimately, fraudulently obtaining U.S. citizenship. The purpose is not to punish Nigussie for the crimes allegedly committed in Ethiopia; but to punish him for violating immigration laws of the United States.

This practice is highly consistent across U.S. courts. Europeans, however, have a differing approach in cases similar to Nigussie’s. Favoring universal jurisdiction, some courts in Europe allowed to try Red Terror fugitives on the merits of the case, for international crimes. For example, on 15 December 2017, a Dutch District court found 63-year old Eshetu Alemu guilty of war crimes, including arbitrary detention, inhumane treatment, torture and murder in relation to his role in the Red Terror. Eshetu was sentenced to life in prison in the Netherlands, after he was judged in absentia and sentenced to death by a court in Ethiopia on 12 December 2006.

Fair trial concerns

Fair trial is one of the hallmark of the U.S. justice system, arguably. Nevertheless, one cannot discount the possible risk in Nigussie’s case. The U.S. government’s leading evidence against Nigussie is an authenticated two-page ledger which had been created and maintained by the Dergue regime. The ledger, according to the U.S. government, listed names of individuals, weapons, ammunition, and their signatures. Nigussie’s name appeared twice along arms and ammunition he might have received. The judge ruled that “there is no reason to doubt that the document is what the proponent claims it is.” Statements in an ancient document are admissible, as an exception to the rule against hearsay. As a result, the court thinks that the probative value of the ledger is clear. However, the defense could push further requiring the government to prove that the ledger doesn’t carry a content that is hearsay in itself; or worst yet, a hearsay within a hearsay. Nigussie’s lawyers have already argued that there is a mismatch of signature on his naturalization documents and the 1978 historical ledger. The expert witness for the government testified, however, that “it is not uncommon for an individual's signature to change over such long periods of time.” Thus, “the exemplars of the defendant's signature appearing on these two immigration forms are of little persuasive value.” This might look like shifting the burden of proof.

The defense also raised concern about whether the copy of the ledger is an accurate copy of the original document. In response to Nigussie’s assertion that alterations or additions could have been made to the copy of the ledger, the court said that “such a bald assertion is utterly insufficient to raise a genuine concern about the accuracy of the copy the government seeks to introduce because the defendant has provided only a hypothetical basis, as opposed to an actual basis, on which to conclude that the copy is inaccurate and therefore inadmissible.” The court further relied on the government’s witness testimony that “the Special Prosecution Office (SPO) stamp which appears on the Ledger demonstrates that the Ethiopian Federal High Court verified that the copy of the Ledger stored in the court's evidence folder was an accurate copy of the original.” The defendant’s motion was rejected.

The mastermind is free

In the absence of an effective and digitalized national archive system in Ethiopia, the possibility of falsifying and imitating the official stamp of the SPO on the ledger can’t be underestimated. Falsifying government documents is not uncommon practice in Ethiopia. In the face of low ethical accountability on the part of archive employees, it may be risky to rely on the ledger as conclusive evidence.

But whatever the outcome of Nigussie’s case, the case shows that the demand for justice on the Red Terror period is still catching up with some people in a transnational legal context. His trial will provide space to tell the story of Red Terror. One paradox of justice will remain: Nigussie, the 18-year old youth, who was arguably among the youngest civil interrogators under Red Terror, is being tried while Mengistu Hailemariam, the mastermind of the violence, still enjoys sovereign protection and a luxury life in Zimbabwe, where he escaped in 1991.

DR HENOK GABISA

DR HENOK GABISA

Dr. Henok Gabisa is a Professor at Washington and Lee University School of Law, Lexington, Virginia. He also represents victims of gross human rights violations before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. He has a book coming up on “Justice System Reform in Post-Conflict Africa.” He tweets at @henokgabisa.