No new publication on Rwanda escapes François-Xavier Gasimba, writer and professor of literature at the University of Rwanda. As a privileged observer, he notes that among the few Rwandans who have taken up the theme of the Tutsi genocide, survivors are in the forefront "because literature, like music, was part of the way of dealing with the trauma". These survivors have "become aware of the need to show that they exist and want to survive after the ordeal imposed on them", continues Gasimba, for whom this literature is characterized by "openness and generosity”.

"Through stories, plays, cartoons and essays, writers denounce the rumours, stereotypes, prejudices and political manipulations that are at the root of the genocide ideology," explains the Rwandan academic. The lack of Rwandan writers, he believes, is bad for society, carrying the risk of "leaving space for denial of the genocide against the Tutsis, obscurantism and closed-mindedness, without any innovation or creativity".

Writing as mourning

Among the pioneers of Rwandan literature on the genocide is Yolande Mukagasana, an anaesthetist nurse and genocide survivor who says nothing predisposed her to a career as a writer. In an interview, she told JusticeInfo how she used her pen to fulfil an obligation of remembrance. "I started writing during the genocide. I didn't think I'd write a book. I just wrote the dates that my loved ones were killed so I wouldn't forget them. I didn't even hope to survive. When I arrived in Kabuga [a town on the eastern outskirts of Kigali], which had been liberated by the Rwandan Patriotic Front, other people were looking for food but I had only one need: a pencil and paper. I started writing instead of talking," recalls this woman who lost her husband and children during the genocide.

When she arrived in Belgium in 1995, she met various psychotherapists on the advice of friends, but none of them managed to calm her pain. "The only thing that could help me was my notebook. It is thanks to my writing that I was able to mourn my loved ones. I felt a great sorrow, as if I had an abscess at the back of my throat and a heart too heavy for my chest."

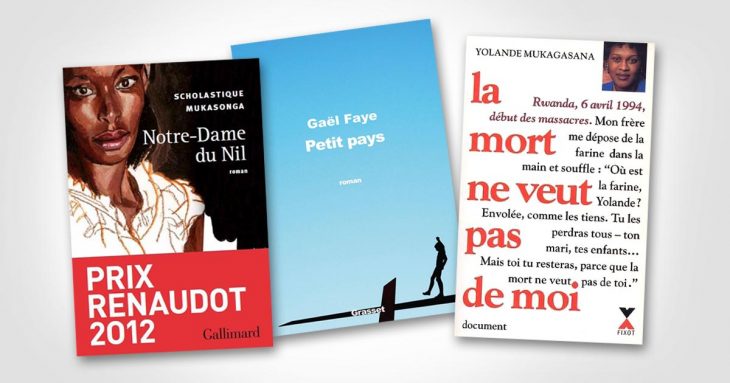

Since 1997, she has published or co-published half a dozen books. The best known is “Death Does Not Want Me”, which has been translated into Italian, Flemish, Turkish, Norwegian, Danish, Hebrew, Portuguese and English. In this poignant literary testimony, the author not only tells her story, but also deals with the history of the genocide, justice and prevention, because she feels she has a mission to serve truth and peace in her country.

A Rwandan woman wins the Renaudot

Other writers followed, including Scholastica Mukasonga. In 1960, Mukasonga's family, originally from Gikongoro in southern Rwanda, was displaced to Nyamata in the Bugesera region near the border with Burundi. It was the time of the first anti-Tutsi pogroms and Mukasonga was then four years old. In 1973 she was expelled from school and took refuge in Burundi, where she studied as a social worker before marrying a French development worker. Living in the north-east of France since 1992, she learned through the media of the killing during the genocide of her family, who had remained in Rwanda. "I wasn't with them when they were cut down with a machete. How could I continue to live during the days of their death?" she writes in “Inyenzi” (Cockroaches).

The author believes this genocide was planned, that it would happen one day, that the only unknown was the circumstances under which each of the victims would be killed. "In Nyamata, we had long since accepted that our deliverance was death. We had lived in expectation of it, always on the lookout for its approach, inventing and reinventing ways to escape it. Mothers trembled with anguish as they gave birth to boys who would become Inyenzi and so could be humiliated, hunted down and murdered with impunity. We were tired and sometimes we gave in to the desire to die. Yes, we were ready to accept death, but not the one we were given. We were Inyenzi, all you had to do was crush us like cockroaches all of a sudden. But people took pleasure in our agony.

In a biographical novel, "The Barefoot Woman", Scholastique Mukasonga pays tribute to her mother, for whom she was unable to be present at the last. "Mum, I was not there to cover your body and all I have left is words - words in a language you didn't understand - to do as you asked. I am alone with my poor words, and my sentences on the paper weave and reweave the shroud of your absent body.”

“I don’t want a Tutsi Virgin Mary”

But it is above all thanks to "Our Lady of the Nile" that Scholastica Mukasonga gained her acclaim in literature. In this novel, which won the prestigious Renaudot Prize in France in 2012, the reader is taken to an imaginary school for young girls, Notre-Dame du Nil, in the early 1970s. This Catholic boarding school, which is reminiscent of a convent, is nevertheless far from a haven of peace. In its dormitories, toilets, in the courtyard, there is anxiety, fear, discrimination and even hatred, often mixed with contempt. Tutsis make up 10% of the students. In a simple, sober but extraordinarily rich style, the book evokes all the seeds and ingredients of the genocide that took place in 1994. The few Tutsi girls suffer from all kinds of harassment and exclusion on a daily basis, as if they were in exile in their own country.

The book’s main character is Gloriosa, a final year student and daughter of a Hutu minister. As a committee member of the Activist Rwandan Youth, she is the “eye” of the majority Hutu people’s party. Her activist zeal, veering towards the grotesque, leads her to push away anything in her path that reminds her of the Tutsi ethnic group. She takes issue with the statue of the Virgin Mary, finding that her nose is too aquiline, and therefore too Tutsi. “It’s a little, straight nose, a Tutsi nose (…) Let’s break the statue’s nose and stick a new one on (…) I’ll talk to my Dad about it (…) He has told me we are going to de-Tutsify schools and

the administration. We want first to de-Tutsify the Holy Virgin.”

Petit Pays wins the Goncourt des Lycéens

Among the youngest Rwandan authors inspired by the genocide, 30-year-old rapper Gaël Faye has been prominent since his first book, Petit pays (Small Country). It is a poetic novel that has won many awards in France, including the Prix Goncourt des lycéens and the Prix du premier roman. This “Small Country” is Burundi, where the narrator, a young boy of about ten years old, lives with his French father and his mother, a Rwandan Tutsi woman in exile. In the early 1990s, the naive and innocent child encounters violence on the streets of Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi, whilst also hearing news from neighbouring Rwanda, his mother's country of origin. When the genocide began in April 1994, his mother returned to find the bodies of her family. "Mum felt helpless, useless. Despite her determination and energy, she could not save anyone. She was witnessing the disappearance of her people and her family without being able to do anything. She was losing her footing, moving away from us and herself. She was being eaten up from the inside. Her face withered, heavy pockets surrounded her eyes and wrinkles lined her forehead."

“Take up your pens, children of Rwanda!”

Other Rwandans have taken up writing to try to heal their wounds or so that future generations should know what happened. But even in Rwanda, some people still find the production insufficient, at least in terms of quantity. "There are very few people who write. Even now, oral culture dominates," says Raphaël Nkaka, a historian teaching at the University of Rwanda.

Yolande Mukagasana agrees, urging her compatriots to follow in her footsteps. "Bana b'u Rwanda ["children of Rwanda", in Kinyarwanda], write your story, otherwise foreigners will write it for you in their own way. Be the messengers of truth, of cohabitation in your differences, because they are riches to be shared. Build bridges that lead to each other through reconciliation, be proud to be Rwandan, so your country will be the cradle of all its children," she says in an interview with JusticeInfo.

A NASCENT CINEMA

Rwandan cinema did not exist before the genocide. Today, it is trying in its own way to capture the history of the genocide. Since 1994, most of the films inspired by the Tutsi genocide have been the work of foreigners. The few Rwandans who have gone behind the camera with scenarios evoking the genocide are almost all young people. The first to choose film so that the world and future generations would know what happened in Rwanda in 1994 was Eric Kabera. His best-known film in Rwanda and abroad is 100 Days, shot at one of the sites of the genocide. This is the very first fiction film on the subject. Produced in collaboration with British documentary filmmaker Nick Hughes, who covered the killings in 1994, this feature film was released in 2001. The central character, Josette, a young Tutsi, seeks refuge in a church in the midst of a massacre. But she finds herself at the mercy of a Hutu priest who abuses her and gets her pregnant. The film denounces the responsibility of the authorities of the time, the role of France and the Church.

Writer, director, producer and sometimes actor, Eric Kabera is aware of the shortcomings of Rwandan cinema. That's why he founded the Kwetu Film Institute, a training centre in the capital, Kigali. "We still have many challenges and most of this comes from lack of financing, culture of cinema,” he says.

The example of “Forgiveness”

Among the young Rwandan filmmakers who have nevertheless been able to break through is Joël Karekezi. His film Le Pardon (Forgiveness) has as its theme reconciliation after the genocide. First presented as a short film, the film won the Golden Impala Award at the Amakula International Film Festival in Uganda. A feature film version was made in 2011 and presented at the Gothenburg International Film Festival, followed by the Seattle International Film Festival (2013), the Chicago International Film Festival and FESPACO. "As Africans, we have a duty to tell our story, without waiting for it to be told by Westerners," says Karekezi. But he deplores the lack of a framework for training and promoting cinema in his country, where priorities are elsewhere.

But Kabera is optimistic. "With the new generation we owe to change it, and it has happened since Rwandans now do appreciate the appetite of visuals and film and TV content,” he says.