JUSTICEINFO.NET: What do you remember about June 5, 2000?

ALINE ENGBE: This is a sad date for me, my family and the Congolese people, because it reminds us of the beginning of the conflict that would later be called the "six-day war", which we suffered in Kisangani from June 5 to 10, 2000. In the morning of June 5, the Rwandan and Ugandan armies that were supporting factions of the RCD [Rassemblement congolais pour la démocratie] rebellion had engaged in a fierce battle in the middle of the city of Kisangani. Around 10 a.m. as I was preparing to go to school, we heard loud bursts of heavy and light weapons. In the absence of my parents, who had already left for work, me and my brothers and sisters remained holed up at home. We thought the situation would immediately return to calm, but not at all, the war was just continuing and the situation was getting worse every day. We had no water or electricity. What little supplies we had were exhausted.

Our family home was on the avenue leading to the plateau. Unfortunately, it was close to where the Rwandans [soldiers] had just installed themselves. While we were still under fire, we saw some of them climbing over the enclosure and asking us to evacuate the area. The family agreed to leave them the house. As soon as we reached our gate, we discovered the horrors of this dirty war. On the avenue, corpses lay on the ground, civilians lay wounded with no help. We had to jump over them to reach the shelter of a tent, hundreds of meters away. Unfortunately, it was near our place of refuge that the opposing group of Ugandans had just settled. Refuge here lasted only a few minutes, because we were very quickly forced to go to our other family home further away, in the commune of Tshopo.

Was that the end of your ordeal?

Unfortunately not. Because there, a shell fell on the roof of the house and destroyed everything underneath. There were no people in the room, thank God, and no one died. The city was no longer liveable, so we decided to leave to find refuge towards Buta [in the current Bas-Uélé]. This was after we shared the very last meal and prayer with the family. Along the way, we met displaced people turning back after having crossed the Tshopo bridge and encountered Rwandans who were massacring civilians. It was total despair. Life no longer made sense. More than 6,600 shells were fired at this city of 1,910 km2. In six days, more than 1,000 civilians were killed, more than 3,000 wounded and more than 300 buildings destroyed. Kisangani was martyred by foreign armies. These were really war crimes and crimes against humanity.

On the sixth day, the war ended. My family decided to seek refuge in Kinshasa [more than 2,500 km to the southwest by road], via the former province of Equateur, the Central African Republic and Congo-Brazzaville.

19 years later, what do the victims want?

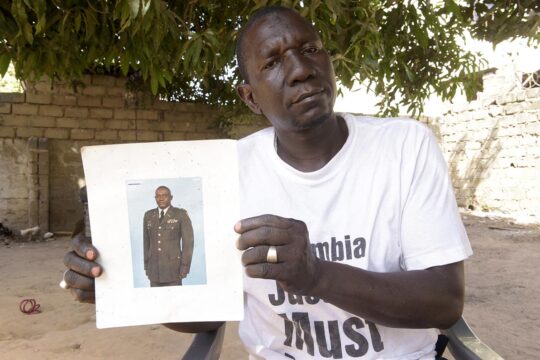

We continue to demand truth, justice and reparation. The truth, because we still don't know why we have suffered so much from a war between foreign armies. We must shed light on this past in order to share responsibility, so that such crimes never happen again in our country. Justice, because we want to see the perpetrators punished, so that it be a warning to all instigators of armed conflicts. Reparation, because it is the right of victims to be compensated for the harm they have suffered. Today, we are nearly 3,000 victim families. There are people who can no longer move because of their physical disability and who have no means of equipping themselves with crutches, people whose loved ones have been massacred and who are living in a situation of terrible trauma. There are also people who are forced to take medication every day because they still have leftover shrapnel in their bodies. To this day, Kisangani is in the same situation as it was nineteen years ago: hundreds of buildings destroyed, never repaired. Homeless families live under the stars. This is deplorable! We want compensation, but also the erection of a memorial. This is a very important work of remembrance.

Why is the memorial so important to the victims?

It is an important work of remembrance so that history can be a testimony to the horrors of war experienced in Kisangani. Barely inaugurated, we saw our Head of State [Felix Tshisekedi, elected President of the DRC in December 2018], during his first tours abroad, bow before memorials in some countries [in Rwanda and the United States]. Why not consider building ours, which will honour the memory of the compatriots massacred during the six-day war? A monument on which the names of the victims, for example, should be engraved. It is a question of memory, remembrance and bearing witness, so that humanity can know the horrors caused by Rwanda and Uganda in Kisangani, so that every time there is a commemoration, we can go to the place to pay tribute to the memory of our loved ones.

What do you think is blocking the compensation of victims?

This is also our question. In 2005, the International Court of Justice ordered Uganda to compensate victims of its human rights violations in Congo-Kinshasa, including the crimes of Kisangani. The Congolese government came to identify the victims and give them assistance tokens. We have even created a Solidarity Fund for war victims to prepare to coordinate reparation. But fourteen years later, no action has been taken, either by Uganda or by the Congolese government. In 2018, we went as a delegation to meet the authorities in Kinshasa, but nothing is moving forward.

What is true is that the follow-up to the Uganda sentencing is suspicious. After the sentence of the International Court of Justice, Congo-Kinshasa lawyer Tshibangu Kalala handed the case over to the Congolese Minister of Justice, Alexis Tambwe Mwamba, who also participated in the crimes in one way or another because he had a responsibility in the RCD rebellion, on whose behalf the two foreign armies were fighting. He is keeping the file and we wonder why this silence? Politicians must depoliticize the case. Every time there is an election, they come to beg for our votes promising to support our advocacy for justice and reparation. Once elected, they remain silent. They use our suffering for propaganda purposes. It's making fun of us. We are fighting not for favours, but for our rights.

Do you think that the advent of a new government could change the situation?

Our regret is that 19 years after a massacre, our government has remained indifferent. This is unacceptable. Felix Tshisekedi must reassess the case so that there is real justice -- because we should not only expect compensation from Uganda, because at this stage justice is not yet complete. There are those responsible who have not been bothered, for example the Rwandan and Congolese governments. Like Uganda, Rwanda must also be punished, because both of them were involved in the commission of these crimes. Also the Congolese government should not believe that it is blameless. It has a share of responsibility and must compensate, because it has failed to protect its citizens, it failed to prevent the commission of crimes on its soil. It's like the children of two neighbours who come to break into your house in the presence of the heads of household. If the neighbours do not come to make reparation, the heads of household should not cross their arms in the face of the damage. This is the case in our country. A government that has failed to protect its citizens must make amends.