Kibore Cheruiyot Ngasura was just a small boy when his family was violently expelled from their ancestral land in Kenya's lush tea-growing western highlands by British colonisers, and banished never to return.

Eighty-five years later he still bristles at the memory, recalling the fear and confusion as his community was marched to a distant, unfamiliar place, and people around him begged their white overseer for answers. "They asked him, 'What wrong did we do? Why are you punishing us like this?" said 94-year-old Ngasura, the only living survivor of a mass deportation in 1934 from Kericho, where rolling green hillsides ripple with Kenya's world-famous tea.

It is a question those forced off their land over decades in Kericho have been asking ever since. Fed up with being ignored, the Kipsigis and Talai peoples have urged a United Nations special investigator to open an inquiry into their plight.

British and Kenyan lawyers representing the victims will on Wednesday make their first visit to Kericho since filing an official complaint with the UN, accusing the UK government of failing to account for this colonial-era injustice. They allege that the British army and colonial administrators deployed rape, murder and arson to seize swathes of arable land in Kericho from its traditional owners -- rights violations for which nobody has ever answered.

The victims - more than 100,000 are signatories to the UN complaint - want an apology, and reparations for their homeland being usurped and reallocated to white settlers, who turned the fertile soils to cultivating tea.

Kericho boasts some of Kenya's most profitable agricultural land -- but the Kipsigis and Talai say they reap none of the benefit. The land today is largely owned by corporate giants such as Unilever, which sources tea from Kericho for some of its best-selling brands like Lipton.

"Blood tea"

The alleged expropriation of land began in the early 20th century but accelerated from the 1920s, after Kericho's exceptional suitability for tea was realised. "There is blood in the tea," said Godfrey Sang, a historian whose grandfather's land was doled out to white farmers. "People were killed. Livestock was stolen. Land was taken. Women were raped... And a crop was planted."

Lawyers pushing for UN special rapporteur Fabian Salvioli to launch an inquiry say the intentional displacement and resettlement of Kipsigis and Talai occurred when Kenya was under the Crown, making the UK responsible under international law. The UK Foreign Office, in a statement to AFP, said it supported the work of UN special rapporteurs, and would "respond accordingly" if contacted by Salvioli, the independent expert for the promotion of justice.

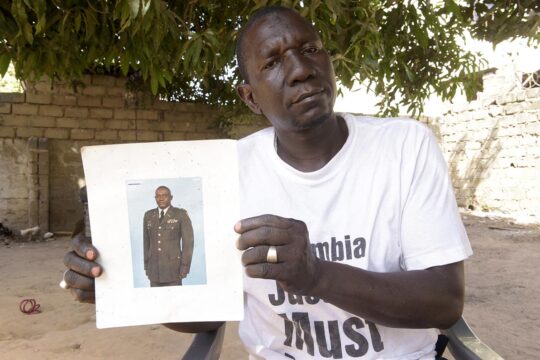

Those thrown off their land were herded into so-called "native reserves", marginal areas where conditions were often appalling. In an extreme case, the entire Talai clan -- hundreds of families, including that of 10-year-old Ngasura -- was deported by decree in 1934 and interned in Gwasi, a barren land two-weeks walk to the west, where malaria was endemic and water scarce. "Life was so difficult. People were dying," said Ngasura, speaking through a translator, surrounded by his extended family. Today, many Kipsigis and Talai live as squatters, humiliated and landless, generations after their forebears were exiled from Kericho's verdant slopes, land known locally as the "White Highlands". Most possess nothing more of their past than chunks of pottery and other fragments, unearthed surreptitiously from beneath the tea fields: proof, they say, that their people once lived there. "It is very bitter, to see where you used to live, and (know) you were chased away," said Joel Kimutai Kimetto, staring wistfully at distant hills where his father's land was razed, and tea planted in its place.

"Stolen property"

A spokesman for Unilever Kenya Ltd told AFP by email they would not comment on colonial-era claims against the UK. Williamson Fine Tea, and James Finlay Limited, two other multinationals with major tea estates in Kericho, did not reply to requests for comment. "First of all, they need to acknowledge that it is stolen property," said Kericho County Governor Paul Chepkwony, who has fought for reparations for years.

In March, they scored a rare victory when Kenya's National Land Commission ruled that the Kipsigis and Talai did suffer injustices, and recommended the UK apologise. But efforts to broker dialogue have not been successful, said Joel Kimutai Bosek, a Kipsigis lawyer representing his people.

The UK has faced a slew of compensation claims from across its former empire, including from Kenya. In 2013, the government paid reparations to victims of its bloody crackdown on the 1950s Mau Mau rebellion against colonial rule in Kenya. But similar appeals have failed. Rodney Dixon QC, a British lawyer representing the Kipsigis and Talai who is visiting Kericho this week, said the UN special rapporteur could assist in mediating a settlement, and had experience investigating long-past historic abuses. "This is a precedent that could equally apply here," Dixon told reporters in Geneva in September.

Ngasura, reaching the end of his years, just wants an apology before he dies. "After that, we would shake the hands of the British, and forget the past," he said.