In the past few days, one of the most fast-trending slogans on Gambian social media sites has been “legal junglers”. This is to name the legal minds who helped entrenched the 1994-2017 military regime of Yahya Jammeh, and it refers to the “Junglers”, the feared hit-squad operating on the orders Jammeh.

The highest qualification among soldiers who took power in Gambia in July 1994 was a “A” level held by Edward Singhateh, the number 2 of the coup makers. Soon, these men would nevertheless appear more sophisticated in grasping more power, politically and legally—aided by a plethora of decrees they enacted.

In the past week, two prominent Gambian lawyers who reportedly had significant influence on the drafting of some of these decrees—Fafa Edrissa Mbai and Amie Bensouda—faced the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC), a body charged with investigating human rights violations under Jammeh’s rule.

Ruling by decree

Mbai was the junta’s first Justice Minister who stayed on with them for six months while Amie Bensouda was their first Solicitor General. A veteran lawyer, Mbai had already been Gambia’s Justice Minister from May 1982 to June 1984. His appointment under the new military junta made him one of few civilians in that government. He didn’t last long. By February 1995, he was fired. But during his time as Minister, he was also sitting in the Executive Council, a body that effectively replaced the parliament in making laws.

The Council started to issue a pile of decrees, a large number of which were giving the military leaders sweeping powers. Mbai participated in the creation of the decrees at three levels: drafting them at the ministry, deliberating on them in the cabinet and passing them in the Executive Council.

Before the TRRC, the lawyer only took collective responsibility for decrees 7 to 25 that were made while he was in office. However, he denied playing any critical role in their drafting and passing. “Soldiers believed, against better advice, that decrees were the most effective way of helping them achieve their objectives,” he argued, adding he even earned the nick-name “Uncle human rights” from the Junta members. “They were hell-bent on running on anyone who stood their way and they did. The tragedy is that the initial intentions they held changed when they tested political power and their objectives changed for the worst.”

Dialogue of the deaf

Mbai claimed he had a fringe role in the scheme of things. Before the Commission, it turned out a little different. While on official visit in Britain in December 1994 to ask the former British colony to lift a ban on The Gambia and allow tourists to come back to the West African country, he was interviewed on the BBC. “There is no mess,” he then said of the junta’s actions. “I think Captain Jammeh’s mission is to cleanse up the mess that has been created and perpetuated for over 30 years.” He eloquently defended the military regime and spoke of their desire to ensure the reign of rule of law in the country.

“In all honesty, do these decrees really reflect a respect for rule of law?” asked the TRRC Lead counsel Essa Faal.

“These decrees were the laws of the state at that time.”

“That does not answer my question. The question is whether these decrees would reflect the respect for rule of law?”

“These decrees provided that there will be a commission of inquiry.”

“Can you answer the question, sir?” repeated Faal three more times.

“I am not defending the decrees”, Mbai dithered around.

“But you defended them in your interview. You said those things were established to demonstrate our respect for the rule of law.”

“No, I did not say that. These decrees were the laws at the time.”

“Were they just laws?”

“They were good laws and bad laws.”

Faal tried again, in vain, before making one last attempt.

“My question is: would this be the standard of good laws in any society?”

“If these decrees violate human rights, then they are not good laws,” answered Mbai.

“Exactly, and these decrees violate human rights.”

“Then they are not good laws.”

The long-lasting impact of the junta’s decrees

At the time of the coup on July 22, 1994, a popular Gambian corporate lawyer Amie Bensouda, then the Solicitor General, was abroad. Back into the country, she was effectively in charge of the Justice Ministry for 2 weeks prior to the appointment of Mbai as Justice Minister. Her former boss Hassan Jallow—today Gambia’s Chief Justice—was in military detention with a number of top officials of the toppled civilian government. On July 29, under “Bensouda’s watch”, Decree No. 1 was issued by the junta, suspending parts of the 1970 constitution and with it, the parliament. “The Armed Forces Provisional Ruling Council shall have power to make laws for the peace, order and good government of The Gambia with respect to any matter,” states Decree No. 1.

The decrees also gave the junta judicial powers, in some cases ousting the courts’ jurisdiction to even question them. “The validity of this or any other decree shall not be questioned in any court of law,” states Decree No. 1.

Six months into this regime, Mbai was dismissed, together with Amie Bensouda. A Commission was established by the Junta and headed by Omar Alghali, a Sierra Leonean lawyer who would later become the Chief Justice. It found Mbai to owe the state 1.5 million dalasi (about 24,000 in today’s euros) in tax arrears. Mbai filed a suit at the country’s Supreme Court in November 1996, challenging the findings of the Commission. But as fate would have it, “his” Decree No. 11, as amended by Decree No. 25, which said no court can question a commission established by the military, caught up with him. “My case was stroke out by the Court, [which said] that it had no jurisdiction. The jurisdiction of the Court was ousted by the Decree. I felt very bad,” Mbai testified.

Thereafter, the Inspector General of Police was ordered to seize and sell Mbai’s assets. The proceeds would go to settle his “tax obligations”. He was served an eviction notice from his property in Pipeline, a middle-class neighborhood about 10 minutes drive from Banjul, Gambia’s capital city. For four years, he would go on to stay with his son at the Fajara Hotel, owned by a friend of his.

Several former officials of the deposed government were also evicted the same way. Until today they could not all have their assets back. Another part of Decree No. 11 states that “any order, ruling, finding of fact, seizure, sale or alienation of property or penalty imposed” by any commission of inquiry established by the junta “shall not be questioned or reversed by any Court or other authority under this Constitution or any other law.” A lot of those decrees would later make their way into the new country’s constitution that came into effect in 1997. They remain part of Gambia’s laws to date. A 2020 attempt to abrogate the 1997 Constitution was short-lived after the draft failed to get parliamentary approval. The 1997 Constitution, and its infamous decrees, is still the law of the land.

“You became a victim of your own creation”

Mbai showed the Commission a letter from the national revenue authorities that found that he had in fact overpaid his taxes by D50,000 (about 800 euros today).

“The irony is that all these rights violations happened as a result of the military decrees that were passed during the early days of Jammeh”, said Faal.

“Yes, I agree,” replied Mbai.

“And a lot of those decrees were passed while you were Attorney General [and Minister of Justice]. People were evicted from their homes, arrests were ongoing,” Faal continued.

“I was also evicted from my homes.”

“Yes, but I hate to say that you became a victim of a system you helped created.”

“No. My stance has always been to advise against abuse of human rights.”

“But you said you accept responsibility for these decrees.”

“Yes.”

“So, you became a victim of your own creation.”

“Not my own creation. I did not create these decrees. I didn’t enact the decrees. I was an adviser and my advice was against violations of human rights.”

“Here are 24 decrees, and every single one of them has an inherent rights violations provision in them, you kept advising against them, they kept passing them, and you still continued in office without resigning.”

“I was half way at sea,” he replied enigmatically.

Decree No. 4 proscribed publications, displays, distribution including through newspapers, books, circular pictorial or any other document to further a political agenda. Veteran Gambian politicians Sedia Jatta and Halifa Sallah of the People’s Democratic Organization for Independence and Socialism party would be arrested under this decree for publishing their party’s organ, Foroyaa. Decree No. 8 banned political activities.

And more decrees were passed.

Decree No. 45 established the National Intelligence Agency (NIA), under the Office of the President. It gave the NIA director general the powers to issue search warrants, which is a judicial function. Anyone aggrieved by the NIA could not go to court. You could only report to the country’s president, who could decide or not to appoint a high court judge. Decree No. 57 gave the Minister of the Interior unlimited powers to order the arrest and detention without charge of any person “in the interest of the security, peace, and stability of The Gambia”. It abrogated applications for a writ of habeas corpus. Decree No. 66 extended the period of preventive detention up to 90 days. Decrees 70 and 71 increased the bond required from any independent newspaper publisher from D1000 to D100 000 (today about 1,600 euros).

Amie Bensouda’s denial

Before the TRRC, Amie Bensouda claimed “her” decrees, though they gave the military sweeping powers, were meant to protect the public interest. “I could have said no probably, but what weighed on me was the public interest. Could we contain the excesses of the military? Certainly, decrees were needed. Not for the benefit of the military but for the benefit of the people,” she argued. But available evidence before the Commission suggest otherwise: people’s assets were seized, arrests and indefinite detention occurred, as well as other forms of abuse.

“Are you saying, Mrs. Bensouda, that these military decrees benefitted the public and, considering all the evidence that we have received, that this was a tool by Yahya Jammeh to entrench himself in power in this country?” asked counsel Sagar Jahateh.

“The decrees that I drafted were in the interest of the public. They incorporated them in the 1997 constitution. That is the choice of the Gambian people, not the Solicitor General or Mrs. Bensouda,” she replied.

“These decrees were churned out very quickly. Within a space of 15 days while you were Acting Attorney General, six decrees had been promulgated. In the instance of Decree No. 1 it was passed within one day after you consulted with the Chairman [Yahya Jammeh].”

“Yes, that is the nature of military rule because they don’t have to take it to anybody. They are the Executive and they are the lawmaking body at the same time.”

“If you look at the provisions of Decree No. 1, it takes precedence over the constitution which was the sole jurisdiction of the Supreme Court at the time. The fact that even the courts could not question the validity of the Decrees, in my view gives them judicial powers because the courts were no longer relevant.”

“I don’t agree. Decree No. 1, as drafted, did not oust the jurisdiction of the courts. It did not suspend the courts.”

“Not expressly but by implication it did.”

“I also don’t agree with that.”

“Can you tell us why? If you are not able to resort to the courts, if the courts are not able to question the validity of the decrees, the decree is supreme to the constitution, then I don’t see what the role of the courts there is.”

“What that means is that the courts do not have the jurisdiction to question whatever is done by decree. But it does not affect the continued existence of the courts. Let me remind you that this provision, in a different formulation, exist in the 1997 Constitution and it is still binding on the courts. So, the courts continue to exist.”

“I did not say the courts did not exist. My point is that as far as this Decree [No. 1] is concerned, the jurisdiction of the court is ousted.”

“In so far as they cannot question the validity of a decree? Yes,” Bensouda conceded.

Bensouda denied that Decree No. 1 set the pace for the entire Constitution to be suspended, including its chapter on fundamental human rights.

“What Decree No. 1 did is to suspend all those provisions which were in the constitution but were no longer relevant to the situation”, she said. “There was no president or cabinet, so the chapter on President and cabinet were suspended. There was no parliament, so the chapter on parliament was suspended. That is what Decree No. 1 did. Now, Decree 30, which came into force in March 1995, actually suspended the human rights provisions in the 1970 Constitution. By then there was a legal team advising the Armed Forces Provisional Ruling Council directly. These were not Gambians and I believe their advice was that there was no place for a human rights chapter in a military government.”

“I believe that even before Decree No. 30 was promulgated, in Decree No. 1 there was no place for human rights,” retorted the TRRC counsel. “The spirit of Decree No. 1 was against protection of fundamental human rights.”

“I don’t agree. Decree No. 1 did not suspend fundamental human rights. It enabled us at the Ministry of Justice to consistently push for the military Junta to respect human rights,” Bensouda claimed.

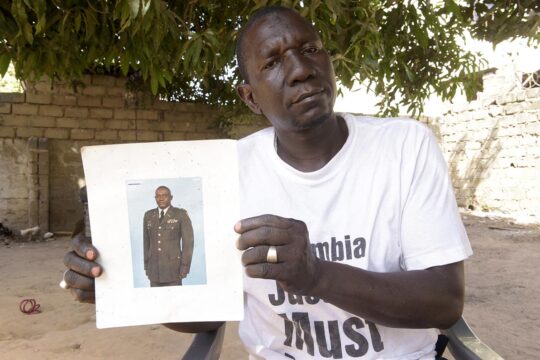

Justice Info has received a letter from a family member of Fafa Edrissa M'Bai, a former Minister of Justice under the military junta in Gambia, in response to this article. In the interests of transparency and fairness, we are publishing in its entirety this letter, which takes issue with our coverage of the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) hearing in which M'Bai was questioned about his role in the early days of former dictator Yahya Jammeh's rule.