Five years ago, the question of reparations was raised strongly by French, Caribbean, American, Brazilian, and English associations, particularly through the demand for reimbursement of compensation paid to slave owners in 1849 - after the abolition of slavery in 1848 - and that imposed on Haiti in 1825. Often perceived as not very serious, out of place, even excessive, this issue questioned us as researchers and pushed us to go and dig into the archives -- not in order to answer questions about the past in a mechanical way, but to provide elements for reflection on these contemporary questions. How do we think about post-slavery? Has indemnity had an impact on post-slavery? What impact on citizenship? Unlike the work of activist associations, we were interested in a scientific approach, that is to say, one based on archives, texts and fieldwork.

The first database on indemnities in the British Empire was born in England. The objective was to work on the constitution of capitalism in Great Britain, i.e. to show how the colonies had participated in the stabilization or even development of the wealth of certain people who were themselves involved in English capitalism. Our approach is different, since it is to create a database from unexplored archives and to see concretely which indemnity, for which amount, was paid to whom; to see how it was distributed and know more about the history of the indemnity.

Haiti and the independence debt

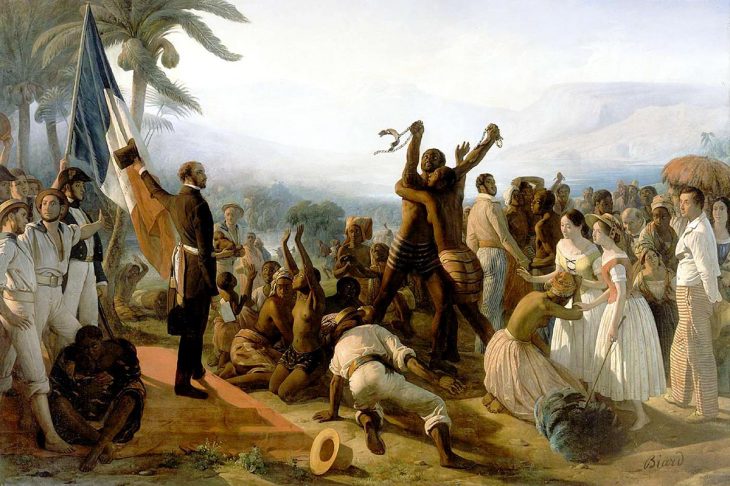

Following the revolt of the slaves of Saint-Domingue on August 23, 1791, the attempt to re-establish slavery by Napoleon in 1802 and the war that followed, Haiti became an independent country on January 1, 1804. It was an earthquake, since this uprising showed that all the enslaved - the term "enslaved" does not reduce the person to his or her status as a slave - could rise up against their masters, even kill them. From that moment on, fear spread; slavery, which had always been more or less stable even though there were revolts and resistance, was under threat and the balance of power in favour of the masters was shifting.

After Haiti, the second abolitionist movement discussed the conditions for abolition of slavery. There were several cases, notably that of the English who, in 1807, decided to abolish the slave trade. Abolishing the slave trade first meant cutting off the supply routes. Then, in 1833, England decided that slavery would be abolished with one specificity: slaves would be free within six years and not immediately. France, however, did not choose a gradual abolition but an immediate one, linked to the establishment of the Republic: equality was for all citizens.

It should be remembered that there was a precedent for this indemnity paid from 1849. It concerns the Haitian state. France asked this new country to pay the "debt of independence". In other words, France recognized Haiti's independence in exchange for the payment of an indemnity amounting to 90 million gold francs, financed by Haiti's economic revenues but also by loans from the Caisse des dépôts et consignations in France. This system maintained Haiti in economic dependence, since the state had to repay both the debt and loans until 1887, and was obliged to take out other loans to balance the country's budget. A real debt spiral was put in place.

Who were the slave owners who got compensation?

Then, in 1849, France paid 126 million gold francs to all the slave colonies of the French imperial domain; not only the owners of the so-called "four old colonies" (Guadeloupe, Guyana, Martinique and Reunion) but also Senegal, Nosy Be and Sainte-Marie of Madagascar. According to economist Thomas Piketty, this sum represents 1.3% of gross national income. The same proportion applied to the gross domestic product today would represent 26 billion euros.

Reunion was the colony that got the most - the amounts were determined according to censuses and surveys - because the island was in the process of developing the sugar industry and there was a plan to make Reunion a new Saint-Domingue. The purchase of slaves and their value was therefore more important than for Martinique and Guadeloupe, which were in a phase of decreasing their slave populations.

While working for the Repairs project on the issue of compensation in Martinique, Jessica Balguy, a doctoral student at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) within the Centre International de Recherches sur les Esclavages et les Postesclavages (Ciresc), was able to show that 30 to 40 percent of those receiving compensation were people of colour, i.e., a category of small property owners. This finding has made the issue of compensation more complex, because we can see that the opposition put forward between whites and blacks does not necessarily work. Indeed, there was an oligarchy of settlers who concentrated their land ownership after 1848, and a sort of scattering of slave ownership among smaller owners, who were people of colour. We discover that the slave relationship is multifaceted and worked in many ways.

Reparations, a demand for equality

As a result, the Repairs database opens up considerable avenues of research. Ours is a more contemporary line of research, where the question of compensation is approached from an economic, legal, and philosophical perspective, and which raises the question of reparation as part of a reflection on restorative and transitional justice. This is the work of Magali Bessone, but there is also a sociological line of research led by Elisabeth Cunin, who coordinated an interactive map that is accessible online. It allows us to ask the following questions: how was the issue of reparations organized within French overseas associations, but also in all countries that experienced slavery? What types of policies were put in place at the time of Emancipation (financial compensation to owners, no compensation, maintenance of economic dependency relationships, etc.) and what contemporary memorial policies were put in place around the memory of slavery (teaching of this issue, commemoration days, memorials, etc.)?

In my opinion, this question of reparations involves a demand for equality that has never really been achieved. To be French is, of course, to have citizenship rights, but we can see very clearly how, in the French West Indies, these rights have always been contained and minimized, subjected to discrimination and socio-racial hierarchies. The issue of reparations underlies the question of what kind of society we want. What do we want to forget? On which subjects is a lid always kept tight?

While our project tends towards equality, I think that there is no taboo subject and that, on the contrary, we must provide scientific tools to think about social issues. Symbolic reparations are very important and considered as such when they produce equality. Reparation is a kind of levelling of a historical fact, where things are put back on an equal footing. And real equality would be a serene, full and complete recognition of the history of slavery, which should not mean an indictment. To accept the history of slavery is to put back into the narrative of French history a piece of the puzzle that allows us to understand the economic and social history but also the political philosophy of France. Justice, equality and fraternity are terms that were also fully grasped by the slaves of Saint-Domingue when they rose up in 1791. They did so in the name of the principles of the French Revolution, in the name of the Declaration of Human and Citizens’ Rights!

This work is therefore only the beginning of new research that will contribute to public debate on these issues.

© Anabell Guerrero

MYRIAM COTTIAS

Myriam Cottias is Director of the International Research Centre on Slavery and Post-Slavery and coordinator of the research project "Repairs: Reparations, compensation and indemnities for slavery (Europe, Americas, Africa) between the 19th to 21st centuries". This project is supported by the International Research Centre on Slavery and Post-Slavery (CNRS); the ISJPS, Institute of Legal and Philosophical Sciences of the Sorbonne (University of Paris 1-Panthéon Sorbonne, CNRS); URMIS, the Migration and Societies Research Unit (IRD, CNRS, University of Paris, University of Côte d'Azur); and the CRHIA, Centre for Research in International and Atlantic History (University of Nantes).