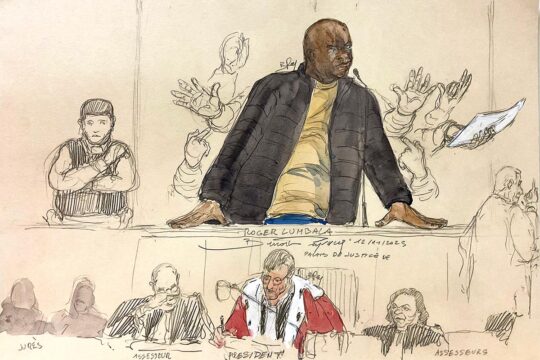

The trial of Hamid Noury, 60, started on August 10 in Stockholm. This Iranian man was arrested in autumn 2019, almost as soon as he disembarked from a plane bringing him to Sweden for a holiday.

In this universal jurisdiction trial, the former Iranian prison official is charged with violations of international humanitarian law and war crimes - including counts of torture and inhuman treatment - and murder. Noury is alleged to have played a significant role in the 1988 summary executions in several prisons across Iran. This is the first time that an actor in this dark episode of Iranian history has faced justice. It is also the "most important war crimes trial that Sweden has seen in recent years", according to Göran Hjalmarsson, a Swedish lawyer specializing in international crimes.

In July 1988, the young Republic of Iran was emerging bloodied from eight years of war with Iraq. Ayatollah Khomeini, Supreme Guide of the Revolution, ordered the execution of prisoners linked to the People's Mujahedin, an Islamic, Marxist-influenced movement allied with the 1979 revolutionaries which turned its weapons against the regime in 1981. Having moved to Iraq, the People's Mujahedin headquarters coordinated multiple attacks on Iranian territory, up to a deadly last lightning offensive in July 1988, just before the signing of a ceasefire between Tehran and Baghdad. In the days that followed, the Supreme Guide issued a fatwa [religious decree] ordering the execution of prisoners still loyal to the Mujahedin.

Thousands of prisoners executed

“Death committees", composed of a religious judge, a prosecutor and an intelligence official, toured the prisons. Prisoners with close or distant ties to the Mujahedin were brought to them. “Some were only guilty of participating in the demonstrations organized by the movement in the early 1980s," Hjalmarsson says indignantly. Those who did not deny their sympathy for the armed group were executed. In less than three weeks, thousands of detainees were killed without further trial. After a brief interruption in mid-August, the executions resumed. This time, left-wing activists were brought before the committees: Communists, Trotskyists, Marxist-Leninists. They were asked if they believed in God. Those who refused to lie, without knowing that their lives depended on their answer, were taken before the death squad. As for the women, they were whipped “into submission”, causing some to die.

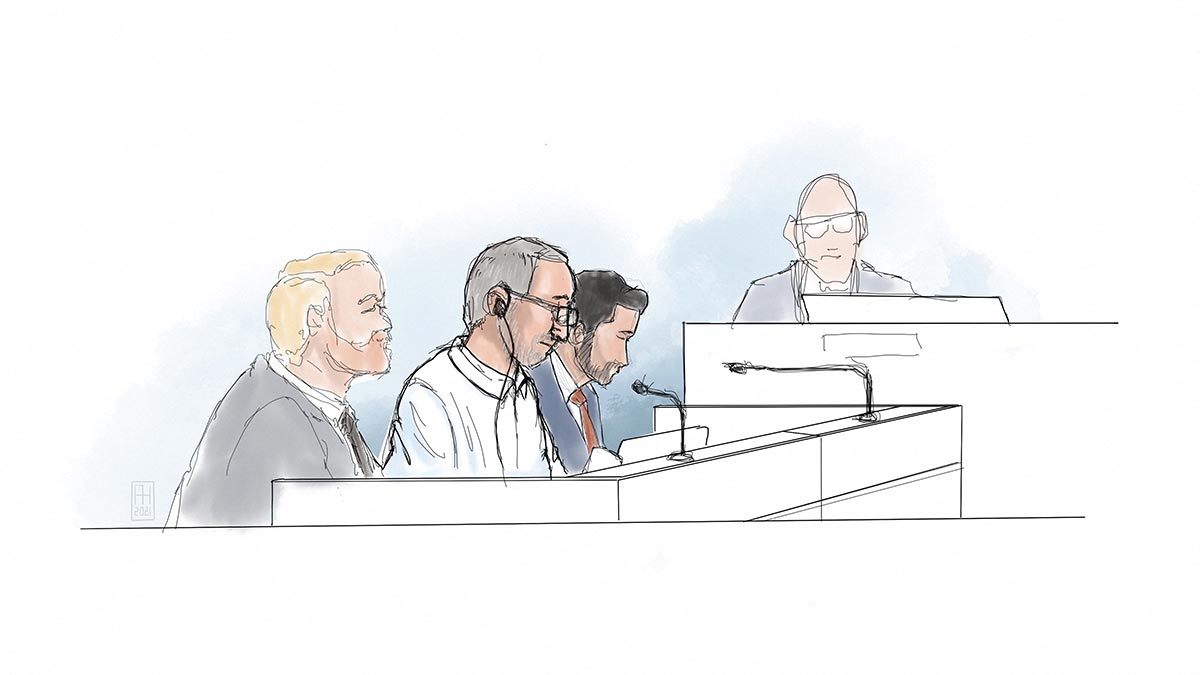

Thirty-three years later, the exact number of prisoners killed remains unknown. Without totally denying that these executions took place, the Iranian regime has always denied having perpetrated a massacre. According to Amnesty International, Tehran has even in recent years gone about removing the mass graves where the bodies were dumped. It is true that in 2012, a "citizens' tribunal" - a symbolic trial organized by victims and human rights organizations in The Hague - tried to shed light on the "crimes against humanity" committed in the 1980s in Iran. But no one responsible has ever been tried. Noury is the first.

Noury, administrator of executions?

The 60-year-old prison official was assistant to the prosecutor of Gohardasht prison, west of Tehran, according to the prosecutor in charge of the case, Kristina Lindhoff-Carleson. He was not part of the “death committee” and did not take part in the decisions, the prosecutor said, but he managed the administrative tasks, helping to select the prisoners sent to the committee and then transferring them to the execution room.

In the indictment, the Lindhoff-Carleson team lists 136 people they believe they can show were killed at Gohardasht during this period. But the prosecutor estimates that "at least 600 to 700 people" were killed in the prison between July and September 1988 -- a massacre for which, she asserts, Noury is one of those responsible.

"The accused is suspected of participating, together with other perpetrators, in these mass executions and, as such, intentionally taking the lives of a large number of prisoners, who sympathised with the Mujahedin and, additionally, of subjecting prisoners to severe suffering which is deemed torture and inhuman treatment,” the indictment states. With an international armed conflict going on between the Iranian regime and the Mujahedin since 1981, these acts are considered by the Swedish justice system to be violations of international humanitarian law and war crimes. In addition, “the accused is suspected of intentionally killing, together with other perpetrators, a large number of prisoners who sympathised with various left wing groups and who were regarded as apostates,” continues the indictment. “These acts are classified as murder according to the Swedish Penal Code since they are not considered to be related to an armed conflict.” There was no armed conflict between the regime and these political groups at the time, "so these acts cannot be prosecuted as war crimes," said Lindhoff-Carleson. And the Swedish Penal Code only recently incorporated the notion of crimes against humanity, in a non-retroactive law. "On the other hand, Swedish justice has universal jurisdiction for the crime of murder," explains the prosecutor. That is why Noury is also prosecuted on this count.

Trapped by ex-son-in-law, victim and lawyer

The accused denies "any involvement in the alleged executions of 1988," his lawyer, Thomas Söderqvist, told AFP. Flying in for a European vacation in November 2019, the 60-year-old never imagined he would fall into a trap - cleverly woven by an unlikely alliance between one of his ex-gendarmes, one of his victims, Iraj Mesdaghi, and London lawyer Kaveh Mousavi. The three knowingly lured him to Sweden, as reported by Libération, while warning the Swedish police of his arrival. “We received information from a London law firm four or five days before Hamid Noury arrived in Sweden," confirms Lindhoff-Carleson. “They sent us a number of documents with enough information for us to decide to open an investigation.”

In the wake of this, a complaint was filed in Stockholm. And when Hamid Noury got off the plane at Arlanda airport, he was picked up by the police and placed in custody. "After his arrest, we had to work very quickly to gather enough evidence to justify his continued detention, with a view to his future indictment," adds lawyer Hjalmarsson, who helped the victims and the London lawyers to build the case. Since then, the number of civil parties, which he represents with three other lawyers, has multiplied. "Among the plaintiffs are both surviving former Mujahedin and the families of slain leftists," Hjalmarsson says. "Many of the survivors recognize Hamid Noury with certainty," he further asserts, "Some will say that more than thirty years have passed, but such a traumatic memory does not disappear." In total, 26 families and 33 former supporters of the Mujahedin have filed civil suits. But more than 70 people, refugees from all over the world, will be heard during this trial, which is to continue until April 2022. “For my clients, this trial has a very symbolic importance," continues their lawyer. “They know that they will probably not get any economic 'compensation' but that is not the issue for them. What is at stake is the feeling of obtaining justice and finally shedding light on what happened in 1988.”

The affair has political impact particularly since the new Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi - who was sworn in on 3 August - is suspected of having taken part in one of these "death committees" when he was deputy prosecutor in Tehran in 1988. Agnès Callamard, secretary general of Amnesty International and former UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions, expressed alarm at the accession to power of a man who should be "investigated for the crimes against humanity of murder, enforced disappearance and torture”. The United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Iran, Javaid Rehman, has called for an independent investigation into the events of 1988 and the role that Raissi played in them.

![An Iranian activist stands in front of thousands of photos of people killed in Iran during the 1988 massacre of political prisoners and more recent anti-regime uprisings [September 2020, near the US Capitol in Washington DC]. © Saul Loeb / AFP Activist in front of thousands of photos of victims of the 1988 massacres in Iran](https://www.justiceinfo.net/wp-content/uploads/Iran-Sweden_1988-massacre-Washington-photo-exhibit_@Saul-Loeb-AFP-730x487.jpg)