In five weeks, more than 60 victims and witnesses were heard out of the 80 who were summoned, stressed Marc Sommerer, president of the Paris Assize Court trying Roger Lumbala. This former rebel leader became a minister in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) before his past caught up with him and he was arrested in France in 2020. On December 10, the judge complained about lack of cooperation from the Congolese government, which protected its deputy prime minister Jean-Pierre Bemba and one of his generals, Constant Ndima, who were called as witnesses. They were named by Lumbala himself and regularly by witnesses as responsible for the infamous “Effacer le tableau” (Wipe the Slate Clean) operation that ravaged the Mambasa region of northeast DRC in 2003. Bemba and Ndima were scheduled to testify via videoconference from the headquarters of the United Nations mission in the DRC. “[French] justice requested that Ndima be heard, but he never responded, and the authorities who received my request never responded,” the judge explained at the close of hearings. “The Congolese authorities said yes, we will comply. The Minister of Justice said yes, we will summon the individuals.” But nothing came of it.

This trial therefore initially had two notable absentees. And then, to these was added the defendant himself. After appearing at the first two hearings, Lumbala decided to boycott the rest of the trial, claiming that the Paris court had no competence to try him. His box remained empty. The defendant also dismissed his lawyers, thus depriving himself of any defence. The parties to the trial contented themselves with the evidence gathered and his statements to the investigating judges to form the court’s decision. Outside the courtroom, Lumbala’s relatives denounced the trial as unbalanced, going so far as to accuse organizations representing the civil parties of recruiting false victims to incriminate Lumbala, on the basis of “promises of money and a stay in Paris”.

But despite these major absences, the court heard -- both in Paris and by videoconference -- victims and witnesses of crimes in Bafwasende, Epulu, Mambasa, Mandima and Isiro, as well as former UN experts, humanitarian workers, researchers, and journalists who worked on crimes in the DRC. It examined reports, including a UN “Mapping” report, and read the press of the time to help clarify Lumbala’s level of responsibility in these crimes.

The RCD-N, an autonomous armed group

The accused has consistently maintained that he was acting under Bemba, as part of their alliance to conquer the territories held by Mbusa Nyamwisi’s RCD-KML. But the facts and testimony have instead shown that the Congolese Rally for Democracy-National (RCD-N), headed by Lumbala, was initially an autonomous armed group that subsequently benefitted from the support of Bemba’s Mouvement de libération du Congo (MLC) after an initial defeat at the hands of Nyamwisi. It was Robert Ombilingo, a former “minister” of Lumbala during the rebellion who came to testify on behalf of his absent defence, who curiously clarified this fact. According to him, when Lumbala arrived in Bafwasende in June 2000, accompanied by a Ugandan contingent, he inherited military deserters from the RCD-KML.

“The soldiers were thousands of kilometres from the original stronghold of the RCD-KML,and because he [Lumbala] had been brought in by Uganda, they rallied to him, and we, the administrators, did the same to protect our jobs,” Ombilingo told the court. Ombilingo was then deputy administrator of the Bafwasende territory and, thanks to his loyalty to the new strongman, he was appointed “minister” of propaganda and mobilization for the new armed movement launched by Lumbala with a view to gaining popular support in the area he came from. The RCD-N had soldiers and set up an administration in the Bafwasende region, where Lumbala would rule for a year. He then moved to Isiro, following a botched attempt by Uganda in early 2001 to reunify the three movements (MLC-RCD-KML and RCD-N) beneath his command, under the banner Front de libération du Congo (FLC).

Sharing the spoils

In October 2002, under the command of his military officer Freddy Ngalimu, alias Mopao Mokonzi (“lord” in Lingala, one of the DRC languages), Lumbala unilaterally launched Operation “Effacer le tableau”. Initially, this enabled him to conquer Epulu, Mambasa, and Mandima, amid summary executions, rape, torture, and looting. However, he immediately lost these localities following a counter-offensive by the Congolese People’s Army (APC, the armed wing of Nyamwisi’s RCD-KML). Lumbala sought the support of Bemba, whom Nyamwisi had just driven out of Beni after the FLC initiative failed. Bemba sent him a battalion commanded by Ramsens Widi Divioka, alias “King of Fools”, under the coordination of Constant Ndima, Bemba’s right-hand man, who decided to set up headquarters in Lumbala’s headquarters of Isiro.

“The enemy [RCD-KML] is an unnecessary stain on the board and must be erased.” This is how Ndima explained the concept behind this military operation, which successfully drove Nyamwisi out. In their closing arguments, lawyers for the civil parties concluded that the RCD-N was an armed group that succeeded in a few months “in establishing itself over a territory four times larger than Belgium” to make itself important in a context where “you needed to have troops and effective control over a territory to be present at the negotiating table.” This explains why Lumbala, along with Bemba and Nyamwisi, was a signatory to the Gbadolite ceasefire agreements that ended “Effacer le tableau”, as well as the Pretoria agreements that ended the Second Congo War. And, like other belligerents, he benefitted from the dividends of the transition: “positions, salaries, and cars,” according to the civil parties.

Accomplice to crimes against humanity

By trying to hide in Bemba’s shadow, “Lumbala intends to escape justice”, said civil parties’ lawyer, Jeanne Sulzer. “He is seeking impunity.”

But she believes he was indeed responsible for the “Effacer le tableau” operation. In this, she is joined by attorneys general Nicolas Perron and Claire Thouault, who explained to the judges and jurors in their lengthy closing arguments on December 12 that the operation had been planned, coordinated, and claimed by Lumbala.

“He travelled around the conquered localities in military uniform, presented himself as the Head of State of the Republic, held meetings, boasted of his conquests, presented specific military objectives for conquering Mbusa Nyamwisi’s territory, asked forgiveness for the crimes committed by his soldiers, and never attributed them to anyone else. He had an effective intelligence service, integrated within the civilian population. He collected taxes that he called war efforts,” argued the prosecutors. They accuse Lumbala of complicity in crimes against humanity, through his orders and assistance. “He provided the direct perpetrators with the means to commit the crimes,” argued prosecutor Thouault. “He supplied the soldiers with food and transported ammunition during his trips to the localities. Without this complicity, such crimes could not have reached the scale that characterizes them.”

“Eighty percent of the women who came forward to testify were raped. Seventy percent of them were raped in the presence of their relatives. Forty percent were young girls and 40% of the victims also witnessed other cases of rape,” said lawyer for the civil parties Clémence Bectarte. These acts of rape, she emphasized, have repercussions on the social lives of the victims. They are rejected, abandoned by their husbands or fathers, made to feel dehumanized, and suffer psychological breakdowns. “Roger Lumbala did not rape my clients, but he was a leader who made these crimes possible. He was an accomplice, without whom these crimes would not have been possible.”

The attorneys general denounced the absence of any trials in the area controlled by Lumbala to punish his soldiers for atrocities. They cited the case of two RCD-N soldiers executed in Isiro on Lumbala’s orders and in his presence for committing rape and murder. But they viewed this as an execution without any form of trial, perceived as a response to public pressure following a case of rape committed by a female soldier against an 11-year-old girl in the streets of Isiro.

The victims’ courage

Another lawyer for the civil parties, Clémence Witt, saw Lumbala’s boycott strategy as “contempt for the victims and a denial of their status as victims”, which “hijacked the hearings and made forgiveness impossible by his absence from the dock.”

“Refusing to come here is continuing to show contempt for those who speak out, by saying ‘I owe you nothing’,” said her colleague Claire Denuau. According to Denuau, their clients had no desire to visit Paris, “a city that imposes stifling clothing” on them during this winter, but were driven by exceptional courage and their desire for justice. This prompted them to defy threats of reprisals from Lumbala’s relatives and attacks by Islamists of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF). The ADF is yet another armed group in eastern DRC, which has been ravaged by conflict for more than 30 years, and often ambushes vehicles on the Mambasa-Bunia and Mambasa-Beni roads, two places that allowed the victims to reach Paris via Kinshasa.

“Their bodies and minds are so scarred by the crimes that they still remember them 23 years later. The guilt and shame have been cast on the victims,” Witt said. “For us, justice ends here, but for the victims, it begins there [in the DRC] with fear, fear of reprisals,” added Denuau.

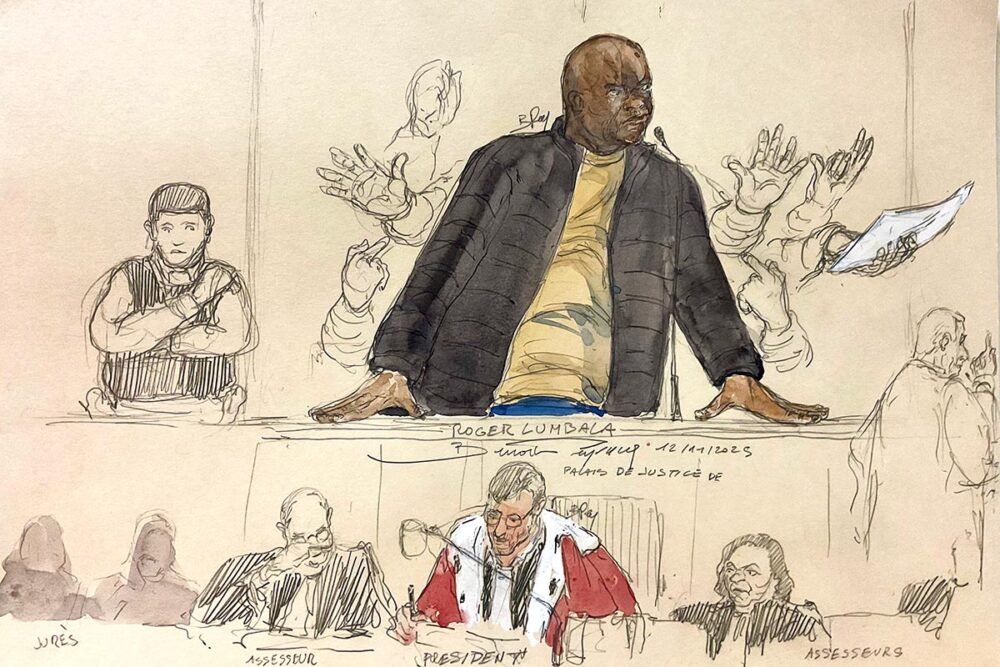

At 5 p.m. on December 15, the judges and jurors entered the courtroom after a long day of deliberation. That morning, the presiding judge had summoned the defendant to attend the verdict. “I note that Lumbala is not here to hear his verdict. It is 5:04 p.m., and I am issuing a summons for him to be here,” said the judge. The hearing was suspended. Fifteen minutes later the two lawyers appointed to defend Lumbala, Hugues Vigier and Phillipe Zeller, entered the courtroom. Police officers got the dock ready. Less than five minutes later, Lumbala entered handcuffed, wearing a black jacket, sweatpants, and sneakers. He agreed to introduce himself and was asked to stand up.

In ten minutes, his fate was sealed. He was found guilty of complicity in crimes against humanity for aiding and abetting acts of torture, rape, and pillage constituting inhuman acts, forced labour and sexual slavery. He was sentenced to 30 years’ in jail, plus a permanent ban from French territory. A written judgment will be sent to him within three days. He has ten days to appeal. A hearing in a civil case, which may rule on reparations, is set for June 30, 2026.

“Impunity still reigns”

Until this verdict, no foreign court had ever convicted anyone for atrocities committed in eastern DRC. In his closing arguments on December 11, a day after Rwanda-supported M23 rebels leading an offensive against Kinshasa captured the strategic town of Uvira in eastern DRC, Bectarte urged the court to send “a strong signal to the warlords that justice can still catch up with them, even 22 years after the events”. “International justice must be able to go after the powerful, the warlords who still commit crimes,” he said. “Impunity continues to reign. Impunity creates the conditions for crimes to be repeated. It is because no one has ever been tried, because those in high places have never been tried, that the crimes continue.” He thinks that “the legitimacy of this court comes from the participation of the victims. This trial is certainly taking place before a French criminal court, but it has been made possible because it is the Congolese victims, Congolese witnesses and Congolese NGOs who have turned to the French justice system. Because there was no other way to obtain justice.”

“The DRC has been turned into a funeral parlour,” added Deniau. “Convicting Lumbala means recognizing that the courage of the victims has not been in vain.”