"My clients were abducted, mistreated, ignored, removed from the world. They are living proof of an unconfessed state crime, and soon there will be no one left to testify," pleaded lawyer Michèle Hirsch on October 14 in one of the plain rooms of the Brussels civil court, which contrasts with the magnificence of the assizes court where trials linked to crimes against humanity are generally held. This is a civil action only.

Léa, Monique, Noëlle, Simone and Marie-José are sitting there, in the front row, facing the judge, in an almost full courtroom. "If they are fighting for this crime to be recognized, it is for their children, their grandchildren, because the trauma is transmitted from generation to generation,” explains Hirsch. “We ask you to name the crime and to condemn the Belgian State." After having buried for years their childhood suffering, these five women decided, at 70 years old, to denounce the injustices inflicted on them and to claim compensation.

A white man could not marry a black woman

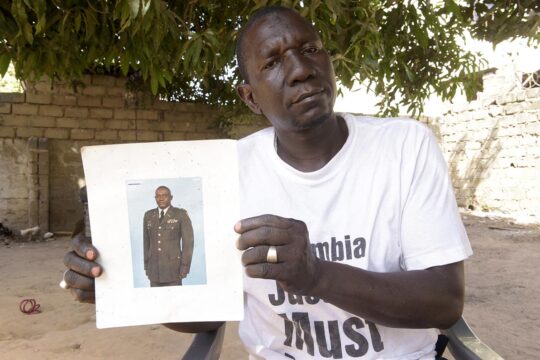

They were all born in the Congo between 1946 and 1950 of a union between a Belgian man and a Congolese woman. They were taken away from their mother, declared of unknown father, then placed in a religious institution like many other mixed-race children. Their number is estimated at 15,000. "We were called children of sin. A white man could not marry a black woman. The child born of this union was considered a child of prostitution," Léa told the press.

Deprived of their identity, the five girls were sent to the religious mission of Katende, in the Kasai province, hundreds of kilometres from their villages. They lived there for several years in miserable conditions, barely clothed, in insalubrious premises, suffering mistreatment and deprivation of food.

In 1960, the Congo’s independence was about to be proclaimed. Faced with unrest in the Kasai province, the sisters of the Katende mission travelled to Lusambo with the young mixed-race children. They abandoned them to try to get on a plane to Belgium, but were unable to do so. They abandoned them a second time when UN trucks arrived at the mission of Katende and took only the clergy.

The five girls, who remained at the mission with about 50 other children, were then sexually abused and raped by militiamen posted there to guard them on the orders of the new Congolese administrator. Later, upon learning of these abuses, the administrator decided to send the girls to Congolese families, but they were never accepted because considered white.

An apology but no compensation

On March 29, 2018, the Belgian parliament passed a resolution that recognized the targeted segregation of mixed-race children and the policy of forced abductions. As a result, it asked the federal government "to examine how, by moral and administrative means, it can repair, on the one hand, the past injustices done to the African mothers from whom their children were abducted and, on the other hand, the harm caused to the mixed-race children resulting from the Belgian colonization." The following year, the Prime Minister - Charles Michel at the time - apologized to the mixed-race children of the Congo on behalf of the Belgian state.

But in 2020, seeing that no action had been taken to compensate the victims, the plaintiffs went to court. The Belgian state, according to their lawyer, must agree to repair its crime. "An apology for history, yes, but no reparations to the victims. The Belgian state did not have the courage to go all the way, to name the crime, because it was liable for damages," Hirsch told the Brussels court.

A crime of the State and the Church

The abductions of mixed-race children were organized by the Belgian state and carried out with the help of the Church, said the lawyer. Officials of the colonizing state were told to organize the abduction of children from mixed marriages and to place them in Catholic missions. From an early age, mixed-race children were taken from their mothers, even though they were not abandoned or neglected, neither orphans nor foundlings.

The lawyer bases her request for recognition of a crime against humanity on two decrees which, according to her, establish a state policy. In 1911, Belgium applied to the Congo these two texts, which legalized the transport and confinement of mixed race children to philanthropic institutions or orphanages. These texts were the decree of July 12, 1890, which delegated to the State the protection of abandoned, orphaned, neglected or foundling children; and the decree of March 4, 1892, which authorized philanthropic and religious associations to take indigenous children placed under State guardianship into agricultural and professional colonies that they ran.

The lawyer for the Belgian state, Clémentine Caillet, contested during the Brussels civil court hearing the qualification of crime against humanity, which is not time-barred. She argued that a supposed fault of the State -- in this case the forced removal of children from their families – must be taken up within a period of five years, and the current action therefore falls on the wrong side of a Statute of Limitations.

Colonial archives still opaque

The request of the five women goes further. They have asked the court to order the Belgian state to produce the archives concerning them. This request, addressed to the Foreign Affairs services concerned, remained unanswered until recently, and the requested documents have still not been made accessible.

Another lawyer for the plaintiffs, Sophie Colmant, described an administrative imbroglio tending towards bad faith. The lawyer strongly criticized the new inventory of colonial archives inaugurated at the end of September, saying there was a poor "GPS" of the 20 kilometres of documents kept in Belgium. Designed, among other things, to allow mixed race children wanting to reconstitute their family history to access the archives concerning them, the tool is ineffective, says Colmant.

"Our clients are asking for full compensation for the harm done but also for the production of archives concerning them. These are administrative documents, exchanges of letters and telegrams within the institutions, civil status registers, etc. The Belgian state has not produced anything, not a single page," exclaimed the lawyer. "Our clients need to take back their lives, their history, to pass it on. They are in search of their identity, their origins.”

The victims have asked for a provisional sum of 50,000 euros each in compensation and the appointment of an expert to evaluate precisely their moral damage, as well as the production of the said archives. In the meantime, they and their lawyers say they are closely following the Special Commission on the Belgian Colonial Past, which is supposed to shed light on Belgium’s shameful practices of in the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. But this commission has still not started work.

The court is deliberating and will render its decision in the coming weeks.