During the reading of the verdict, the defendant stares into space. Anwar Raslan shows no sign of emotion, when the judge convicts him to life imprisonment for complicity in a crime against humanity. He is being watched by a courtroom filled to the brim with Syrian activists and survivors, as well as journalists. After the sentence has been announced and everybody sits back down, Raslan grabs his pen and starts taking notes as he always does. The 58-year-old ex-intelligence officer from Syria will spend at least the next 15 years of his life in prison.

On the 13th of January, after almost two years of trial, the so-called al-Khatib trial in the German city of Koblenz has come to an end. After the conviction of secret service defector Eyad al-Gharib in February 2021, Raslan was the second Syrian intelligence officer to be held accountable for his role in the Assad regime’s crimes. As head of investigations in the general secret service’s branch 251 in Damascus, he has been found responsible for 27 killings, 4.000 cases of torture and serious unlawful detention, one case of rape and two of sexual assault. As they were committed in the framework of a widespread and systematic attack on the civilian population, the court considered the combination of these acts as a crime against humanity.

In their reasoning that lasted from ten o’ clock in the morning until four in the afternoon, the judges depicted again the attack against civilians. These events had already been defined as crimes against humanity in the first verdict against al-Gharib. Back then, head judge Anne Kerber described in detail how the secret services had been terrorizing the population to uphold the Assad family’s rule, and how the situation became worse when the revolution began in 2011 – with mass arrests, systematic torture, and violent attacks on civilians all over Syria. In the verdict against Raslan, Kerber referred to that first ruling, but still took some time to summarize the situation once again.

Raslan maintained power

All that being said, Kerber underlined “that it is not the Syrian regime on trial here, but only the behaviour the defendant is accused of individually” – that is, Raslan’s work in branch 251, where he was head of investigations until he defected in September 2012.

He had been the one who coordinated the staff in the so-called Al-Khatib branch, stated the judges. He had interrogated prisoners, and evaluated his colleagues’ interrogations. Then, he had sent recommendations to his boss on how to proceed with prisoners. “He did not need to order torture, because its use had been common within the secret services for decades”, said Kerber.

She then described how prisoners were abused from the moment of arrival at the branch, how they were tortured during interrogation, beaten at every step, and held in prison conditions so inhumane they amounted to torture. The fact that Raslan was the head of the investigations in the al-Khatib branch during the time of the crimes had never been questioned throughout the trial. Documents, testimonies as well as the defendant’s own statements had left no doubt about that. But Raslan had claimed that he had lost his authority in the branch in mid-2011, after releasing too many prisoners and being seen as disloyal by his superiors.

The judges, however, did not believe him. “It does not seem plausible that the Syrian regime would leave a high-ranking officer in a central position of the secret services, if they doubted his loyalty,” they said. The court cited a witness who had been released thanks to the defendant’s intervention, and took this as proof that he maintained his power in the branch. They cited witnesses who had been interrogated by Raslan as late as 2012, a witness who said he had privileges like a company car until his defection, and another who said he participated in a meeting with high-ranking generals in November 2012. To this, the judges added a few minor contradictions between the defendant’s initial statement and “credible” witness testimonies to argue that “his statement is untrue and has been adapted to his line of defence.”

“A reliable, intelligent and eager technocrat”

It became clear in the judges’ reasoning that they did not buy the image that Raslan had tried to convey of himself: the righteous investigator who tried to defect as soon as things started turning violent, and who had to wait for one and a half years to defect safely with his family. Instead, Kerber described the defendant as “a reliable, intelligent and eager technocrat.” He was not just a small cog in the machinery, she argued, but a colonel who contributed substantially to the regime’s crimes.

“It was also thanks to his work that the regime succeeded in oppressing the opposition and preventing its own fall”, said Kerber, adding that Raslan had a high personal interest in preserving the regime’s position. “He is a careerist who worked his way up in a totalitarian system with which he identified himself. If the regime had fallen, he would have lost his privileges and highly paid position and would surely have faced reprisals.” According to the judges, this was not contradicted by the fact that Raslan might have disagreed with the regime’s exaggerated violence and the mass arrests.

As the prosecution had done before, the judges calculated the number of killings and torture based on witness testimonies they considered credible, reaching the total number of 27 killings and 4.000 cases of torture. For the latter, they estimated the total number of detainees in the branch during the 16-month indictment period. Due to the terrible prison conditions, the lack of oxygen and daylight, the lack of nutrition, hygiene and medical care, and the psychological torment caused by the constant screams in the prison, the court considered the detention in the branch itself a form of torture.

The judges did not find a particular severity in Raslan’s guilt, which means that he can benefit from an early release after having spent 15 years in jail. One of the aspects they assessed in his favour was the fact that he eventually defected – albeit late and in their opinion, not for ethical, but pragmatic reasons: “The court is convinced that he wanted to hold on to his position until the moment he defected. Only when war was at the gates of Damascus, when the situation became difficult and there was shooting everywhere, that is when he decided to defect.”

Focus remains on the release of political prisoners

As the news about Raslan’s life sentence spread out of the courtroom and around the world, dozens of Syrians were celebrating the verdict outside the court building on the banks of the river Rhine. Despite temperatures below zero, visitors had been queueing up as early as 3.30 in the morning to secure one of the 37 seats in the courtroom, but not all had succeeded. The predominant feeling among the Syrian diaspora crowd was relief and happiness about the verdict, but the immediate afterthought was: This was just a very small, first step.

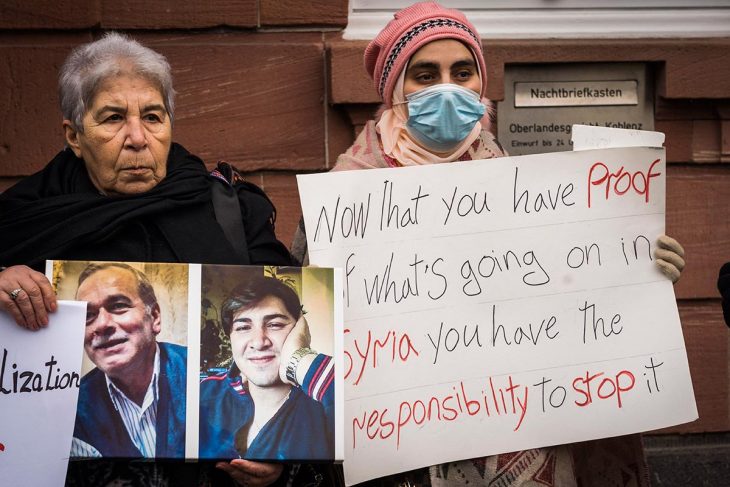

Yasmin Mashaan, from the Caesar Families Association demonstrated with pictures of the five brothers she had lost in Syria outside the court building, alongside other family members of the dead and disappeared. “For me, justice means that my brothers’ dreams from the beginning of the Syrian uprising would come true: a just, democratic and equal state.” She expressed her worry that this first ruling might cloud the international community’s view, making them think that justice had been done. For her, the focus remains on the release of all political prisoners in Syria and on an investigation into the whereabouts of her loved ones.

“This is just the beginning of a wider struggle”, said Ameenah Sawwan from The Syria Campaign, pointing out that a more comprehensive form of justice was needed. “It is difficult to see justice without senior figures of the Syrian regime being held accountable.” She added that it had been hard for her to hear the crimes described in the verdict, knowing that “this is not history. This is happening right now in Syria, thousands of kilometres away.”

That defectors like al-Gharib and Raslan are put on trial, while the Syrian regime is still in place, has been a controversial aspect of this trial. It was discussed more widely after the first verdict, because defendant al-Gharib had been of very low rank, had defected early and had shared all his knowledge with the German police. The sentiments about Raslan were a little clearer due to his stellar career in the secret services, his late defection, and his reluctance to share inside knowledge with German officials or through his statements in court.

Defence did not see individual guilt

In a press conference after the verdict, Raslan’s lawyer Yorck Fratzky announced that they would appeal the judgement. “Even though the court came to a different conclusion, Mr. Raslan was ultimately convicted as a representative of the regime”, he said. “The defence did not see that individual guilt or imputation.” In his final plea a week before the verdict, Fratzky had argued that most Syrian survivors and activists following the trial were not interested in Raslan personally, but cared about what was happening in Syria as a whole.

The al-Khatib trial may have built a foundation for future trials, but it has also shown the difficulties and flaws of trials under the principle of universal jurisdiction. One of them was the lack of protection for witnesses’ families in Syria, potentially endangered by their testimonies. Another issue that civil society organisations, journalists and academics, as well as victims’ representatives criticized time and again was that this historic trial was not recorded and that there was no translation for Arabic speakers in the public gallery.

“As a Syrian, I felt excluded from the process”, said Sawwan, disillusioned after almost two years of trial. Even though she was happy about Raslan’s conviction, she no longer believed that this trial was about Syrians. “It is a German trial taking place in Germany. Raslan is being tried, because he is here, because he is endangering German peace, and because it’s a political win.”

With the first trial on Syrian state torture coming to an end, the next one has already started. On Wednesday, before the higher regional court of Frankfurt, Germany, the trial of a Syrian doctor, Alaa Moussa, has started. He is accused of crimes against humanity for torturing detainees and killing one of them in the military hospitals of Homs and Damascus.