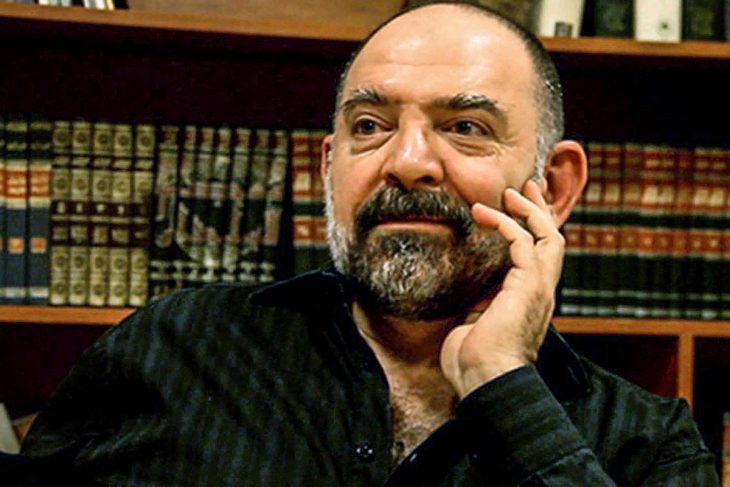

On the night of February 3 to 4, 2021, Lokman Slim was murdered near Nabatiyeh in southern Lebanon. His body was found in his rental car. He was executed with six bullets to the torso and head. No one claimed the attack.

On February 3, 2022, the day for commemorating the murder of this independent Lebanese intellectual of Shiite faith, the Lokman Slim Foundation was officially launched in Beirut. Its purpose is to document and analyse political assassinations particularly in Lebanon but also countries in the Middle East and North Africa region, which have been plagued since independence by armed conflicts and political crises causing serious violence against civilians.

Through his NGO UMAM Documentation and Research, Lokman Slim had first worked to preserve the memory of the Lebanese civil war. This centre, founded with his wife Monika Borgmann in 2005, fought amnesia, exposing unhealed wounds and taboos through publications, exhibitions and documentaries, and making its resources available to all. "He kept a space open for discussion and that's one of the reasons he was killed," says Lynn Maalouf, Deputy Regional Director for the Middle East at Amnesty International.

Lokman Slim also documented political assassinations of intellectuals, researchers, journalists and opponents in the region. "He had launched a program entitled 'Who killed whom?'" recalls Hana Jaber. a researcher associate in Contemporary History of the Arab World at Collège de France. His widow and Hana Jaber have decided to pursue this work with the new foundation.

Fighting trivialization of political murders

This new research centre is exceptional in its ambition, since no other centre deals specifically with the issue of political assassinations, even though it haunts all these countries. "When we looked at the creation of these States, we realized that at the time of their construction there were always one or two political crimes, before the balance of power stabilized," notes Hana Jaber, now scientific director of the Lokman Slim Foundation. "Then, with the establishment of authoritarian regimes, the logic of eliminating critics took hold."

The private research, documentation and statistics institute Information International, based in Beirut, has recorded 104 political murders and 94 attempted murders in Lebanon alone between independence in 1943 and the murder of Lokman Slim. No investigation has resulted in a real judicial process, except for the one conducted after the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in February 2005. That investigation, which lasted 15 years involving a UN and a trial in absentia before an international tribunal, came to an inglorious end without much of an outcome. "There is a tradition of political assassinations in Lebanon, which continued after the war. The murders of intellectuals and writers show how certain factionsand certain regimes want to prevent creation of spaces for freedom of expression," says French-Lebanese political scientist Ziad Majed. "It’s important to work against forgetting, against this banality of political murder, against impunity, because this impunity is the poison of the region."

Documenting and explaining the violence

"By political assassinations, we mean not only politicians, but also intellectuals, journalists, religious figures, diplomats, doctors -- in short, any unarmed person killed for expressing their opposition,” Hana Jaber says of the Lokman Slim Foundation's work. This foundation will essentially be doing something that normally falls to the judiciary and the state, but does not intend to replace them, she stresses. "Our idea is to create a database for each murdered person, starting with a technical file: name, date and place of birth, biography, murder, investigation, etc. Then we also want to extend this work with interviews, memories, letters, everything that can restore flesh and speech to the victim. To bring back to life those who have been silenced.”

This work is essential, according to many researchers, to explain that violence is not inherent to the region but has a history and roots; to counter the idea that these countries are doomed to chaos; and to respond to the despair and resignation of its citizens. "For many years, we have had societies based on forgetting and denial," laments Syrian Sana Yazigi, who created the Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution website documenting the Syrian uprising and the war that followed. "To heal our wounds after an assassination, a failed uprising, an explosion, a war, we are not invited nor equipped through laws and rights to seek the causes, analyse and demand justice. For most people, only God is left to save us. We go to church or to the mosque to forget. We shout and pray, then we turn the page. But in order to heal societies, we need to entrench a culture of judicial responsibility: whoever commits a crime will be judged, regardless of their rank, social or political status. In an interview, Lokman said: ‘I hope the Syrians will not follow the Lebanese example... an amnesty can never erase a memory’."

Absence of justice

"This culture of impunity is at the root of the collapse of Lebanon today," says Lynn Maalouf. "Here, all forms of violence have gone unpunished, whether during the 1975-1990 civil war, the post-war Israeli and Syrian occupations, or today." None of the militia or party leaders involved in Lebanon's 15-year conflict have been tried, except for Samir Geagea of the Lebanese Forces militia, who was convicted of killing former prime minister Rachid Karameh and several of his rivals in the Christian camp in 1987. He spent 11 years in prison. He is the only one.

"Those responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity subsequently became members of parliament and politicians, in power and therefore untouchable. The amnesty law that they voted in their own favour in 1991 institutionalized the absence of any trials," recalls Lynn Maalouf. "It is this same political class that has remained in power up to now, and it has perpetuated this culture of impunity.”

Denouncing the negligence of the political class

And the attacks have continued. "Lokman is only the last victim on the list," sighs Hana Jaber. She points out that he was killed shortly after an interview in which he accused the Syrian regime of having brought in the stock of ammonium nitrate responsible for the port explosion in Beirut in August 2020. According to him, Hezbollah, a Shiite political party and very powerful armed group in Lebanon, was to transport it to Syria. Lokman Slim had also received death threats at the time of the 2019 popular uprising, which he supported. For a long time, he denounced the control of Hezbollah and the Amal party over the Lebanese Shiite community, and the negligence of the political class.

The rooms of his family home in Haret Hreik, a southern suburb of Beirut, are overflowing with books, newspapers, films, and memorabilia collected to document these decades whose memory has been swept under the carpet. It is now the foundation bearing his name that will "continue his work," says Hana Jaber.