JUSTICEINFO.NET: What is the general atmosphere in the Western part of Ukraine where you stay right now?

WAYNE JORDASH: Everyone is watching with a degree of horror as the war impacts a large part of the East of Ukraine and of course everybody knows somebody who is impacted or, as with us, had to flee their home. We have friends nearby who’ve also fled, or have family members caught up [with the war]. They have to face this sort of choice of what to do, whether to flee or stay. Every day is taken up with thinking about how to make sure friends and family are safe and what to do if the war gets closer to them or closer to us.

Ukraine was very swift at filing applications before every international jurisdiction available: the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the International Criminal Court (ICC) or the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). How did the Government of Ukraine manage to mobilize so quickly on the legal front?

Each ministry has had years of dealing with these cases since 2014. If you look at the ICJ it pretty much mirrored what the team has already been doing [before this court]. With the ECHR the team was already in place. In the field of war crimes, we’ve been supporting the national prosecutor since 2015 and up to now. In relation to civil society the coalition that was formed to document war crimes has been working on the subject since 2015 too. This is not the first invasion; it’s the continuation of the same invasion: Crimea first, then Donbass, and now the rest of the country. In that sense there has been a similar response from those groups since then.

In the past, Ukrainian authorities were learning about their approach to the ICJ. Prior to their latest claim their suit required both International Humanitarian Law (IHL) experts, which they didn’t have, public international law experts which they did have, and international criminal law experts which they didn’t have. This latest suit was really public international law expertise – and the interpretation of the Genocide Convention - which they did have.

I think the real test is whether they call upon the right expertise if it goes beyond the preliminary stage and requires a proper investigation into whether Ukrainian involvement in the conflict in Donbass could conceivably amount to genocide – which of course it didn’t. But you need proper international criminal law experts, IHL experts to argue it on the merits. The real question is whether Ukraine will deploy those experts which in the past it hasn’t.

Ukraine is fighting the communication battle and it’s an important one.

What’s the value of all these legal initiatives: is it more political than legal at this point?

I think Ukraine is fighting the communication battle and it’s an important one. If there is going to be any possibility of deterring Russia’s behavior, whether by minimizing violations of humanitarian law or communicating to the Russian public what is happening or keeping up the pressure on the international community, then communication is absolutely vital.

We shouldn’t pretend to ourselves that if the ICJ requests provisional measures to stop the invasion effectively – which is what Ukraine is asking for – the Russians are going to listen to that. But it’s absolutely vital from a communication perspective that the international community understands that Ukraine is using the law to try and communicate its argument that the justifications for the invasion are completely baseless, that there was not a glimpse of genocide in Donbass committed by Ukraine. So you call it political or communication or law: ultimately it comes down to communicating that the invasion was legally baseless, that Ukraine has the law on its side.

It’s important that Ukraine did move fast to show that it is a responsible member of the legal community as well as the political community. Irrespective of the fact that Russia will, of course, ignore it.

Each international mechanism is an important piece in Ukraine’s attempt to communicate to the outside world that it is on the right side of the law.

Some experts say that the European Court of Human Rights may be the best way to go…

I think that each international mechanism has a part to play. Each is equally toothless in the face of a Kremlin attempt to ignore international law. But each is an important piece in Ukraine’s attempt to communicate to the outside world that it is on the right side of the law. The ECHR is very relevant to Ukraine’s interstate conflict in that this court stood the greatest challenge to identifying Russia’s role in Donbass and describing it more accurately.

No sensible state disputes that Crimea’s sovereignty remains with Ukraine and that Russia was trying to annex the territory. In the case of Donbass it was less clear because the political positioning was less clear. The UN General Assembly was clear that Russia was supporting the armed groups; it wasn’t clear in terms of whether that Russian support went further and moved towards control of the armed groups. The ECHR was perhaps the only court which is actually looking at that subject more squarely and more comprehensively, and asking the question of whether Russia’s support amounted to some kind of control of part of the territory.

Was Russia in effective control of the armed groups such that human rights obligations are attached to Russia and such that an international conflict arose alongside the non-international armed conflict? You don’t have that question in the ICJ case or at the ICC. To that extent the ECHR is asking more directly relevant questions.

Still, each court has its part to play in piecing together the jigsaw of Russia’s involvement in Ukraine from a legal perspective.

39 states have referred the case of Ukraine to the ICC and the ICC prosecutor has been very prompt to announce the opening of an investigation. But during eight years the ICC has been seized with the situation in Ukraine without making a single move. How do you feel seeing the ICC being called upon and praised as a new hope when it’s appeared as the opposite up to now?

I think the ICC prosecution has been incredibly slow in responding to the conflict, undoubtedly.

Slow is a kind word.

Absolutely. Especially when compared to the oversized expectations that civil society and the Ukrainian government have had from the ICC.

More than 80 communications have been filed to the ICC Office of the Prosecutor over the past 8 years without any result…

Civil society has been filing communication after communication asking the ICC to find that there was a reasonable basis to proceed [with a full investigation], which there undoubtedly is and has been for the whole of those eight years. There is no justification for the delays that have occurred in terms of the law and the facts – none. There is no justification why the preliminary investigation went on for this amount of time – it didn’t have to.

We should still be very cautious in getting too excited as to the role the ICC can play in terms of bringing any form of real accountability.

So what can be hoped from the ICC now?

The ICC Prosecutor can only play a small part in terms of documenting, investigating, adjudicating the massive international law violations that have occurred in Crimea and in Donbass, in the East. We should still be very cautious in getting too excited as to the role the ICC can play in terms of bringing any form of real accountability.

Let’s be realistic: the prosecutor might at best secure additional funds which allow him to enhance its resources and focus on the Ukrainian situation. But what are we talking about: ten investigators? Twenty? We would still be talking about a fraction of the resources that are needed to conduct a proper investigation into the Ukraine situation. So I am not excited by the prosecutor’s newfound focus on Ukraine. I am obviously pleased that there is a newfound energy but let’s face it: even with the most optimistic view, what the ICC prosecutor can do in documenting the widespread and systematic nature of the violations is a small fraction of what is actually needed. Yes, it’s better late than never but what’s needed is for states to step up and support Ukrainian civil society and Ukraine’s Prosecutor General’s Office to actively conduct its own investigations because if we leave it to the ICC it is not going to be sufficient.

It puts the ICC in a position where it has to go after a world power when it has proven to be unable to do so. Since he has taken over as ICC prosecutor Karim Khan has defined a very pragmatic line that seemed to spare powerful nations from its prosecutorial priorities. Is this a change and why would he be more effective now?

The role of the prosecutor has to be also embedded into what can be achieved [politically]. The previous prosecutor didn’t do enough to pressure the Assembly of State Parties (ASP) to fund a proper investigation into Afghanistan, into Georgia and into Ukraine. I don’t see that this previous caution is justified even within the constraint of the resources available and those imposed upon the Office by the international community’s unwillingness to apply the law evenly to the big powers as it is prepared to apply it to the smaller or medium powers.

The new prosecutor’s caution rightly attracted criticism in regard to Afghanistan and the jury is out now whether he is prepared to go after a superpower or at least a stronger power. His recent action in seeking arrest warrants for Russian affiliates in the Georgian situation indicates that we ought not to worry too much about that. But ultimately the prosecutor is always dependent on the ASP willingness to fund it properly. I always come back to the same thing: even with a courageous prosecutor the resources that he has at his fingertips are a fraction of what’s required to pursue proper investigation. Because the obstacles are significant: no access to Crimea, no access to the East.

Why Ukraine never ratified the Rome Statute and joined the ICC as a member state?

There was general support for ratifying the Rome Statute, both across government and civil society but lots of misunderstanding about the effect of doing so. There were many who did not understand the effect of the declarations filed in 2014 [that allowed the ICC to have jurisdiction over Ukraine], or understand the Rome Statute system as a whole, and many mischievous voices fueling that misplaced anxiety. It did not help that none of the big powers, including Russia itself, the US or China were not members of the ICC. This provided the sceptics with the ammunition they needed to suggest that what was good for them, was also good for Ukraine.

We cannot analyse Russia’s latest invasion without the clear departure point which is that Russia invaded Crimea and the East in 2014. You can’t really analyse the current conflict without seeing those crimes and that control.

You have been closely working with Ukraine’s national prosecutors in charge of Crimea and the East on war crimes committed since 2014. Is there any use today of what has been collected all those years or is it going to be buried under the most recent crimes?

There is no simple answer to this question. My organization has spent the last ten months investigating Russia’s role in the East. We were two or three weeks away from publishing the most comprehensive analysis of Russia’s support to armed groups [when the invasion began]. We will publish a report in the coming weeks that show the systemic support and control that Russia has had over the armed groups and term what was initially an internal armed conflict into an international armed conflict both in terms of the scale of the support Russia has offered to the armed groups, financing them, supplying them with weapons and providing political support.

It’s a misconception to talk about an internal armed conflict. It’s a Russian invasion in the East using proxies. The armed groups in the East could not survive, engage in armed conflict, commit international crimes without Russia’s support. They wouldn’t have existed. In my view it is as simple as that and it is what the evidence points very clearly towards. The examination we’ve done, evidence gathered by Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Justice, the General Prosecutor’s Office and the civil society points convincingly to Russia’s involvement in the international crimes in the East and in Crimea.

We cannot analyse Russia’s latest invasion without the clear departure point which is that Russia invaded Crimea and the East in 2014. You can’t really analyse the current conflict without seeing those crimes and that control. The silver lining of the current invasion is that there is a new enthusiasm in the international community or among national authorities from the United Kingdom to the Swedes to the United States to the Irish to the Dutch, to actually provide those resources [to investigate the case].

My organization may be the only one that has been consistently funded in Ukraine to support the national judicial effort since 2015. It’s been incredibly poor. Donor countries were supporting trainings, capacity building, activities which scratch the surface and provide minimum support to Ukrainian authorities and civil society. We were not supported to be able to build cases. It’s very obvious that the international community let Ukraine down in many respects: look at the amount of investigators made available to investigate a single terrorist attack in Lebanon through the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. It’s disappointing, to say the least.

With the latest invasion I have seen those states starting to step into playing the role they should have played in 2014 onwards.

What I don’t want to see happening in Ukraine is civil society and the Prosecutor General’s Office to be left alone to investigate and try to preserve evidence for the purpose of future trial.

Some people suggest there should be an international evidence-gathering mechanism created for Ukraine as there is for Syria. Is it a good idea?

The UN Human Rights Council has resolved to create a commission of inquiry which has the potential within its mandate to mirror the functions of the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) for Syria. It has a mandate to investigate human rights and to preserve and support the investigation of violations of IHL. I think it’s absolutely necessary but my concern is that I am not certain how it does both things, report and investigate for the purpose of trials before national courts and in Ukraine. If you look at the IIIM and previous efforts to support national efforts, they have been absolutely necessary but not sufficient. The IIIM mandate has extended to preserve what has been done by civil society but not necessarily to support them to do it.

There is a coalition of civil society in Ukraine which is formed around organisations that have been doing it since 2014. What I don’t want to see happening in Ukraine is civil society and the Prosecutor General’s Office to be left alone to investigate and try to preserve evidence for the purpose of future trials which may – if we’re lucky - happen in years to come. Crimes should be documented in real time and publicized to the extent possible so that everybody is aware in Ukraine and globally of Russia’s violations of international law. Ukraine’s Prosecutor General’s Office needs substantial help to be able to fulfil its role. It needs expert advisors and investigative experts who can work with the prosecutors. It needs mobile investigative units as was used to good effect in Chechnya in the 90s. Given the challenges of the crime base this support will prove essential.

If we start to focus on an international tribunal which is not the ICC we’ll start to distract from those national efforts. That’s where we might achieve something.

Germany, Spain and Poland have already announced national investigations into war crimes in Ukraine or the crime of aggression. What does it add?

There is a movement among international lawyers over the last week to create an international tribunal to try the crime of aggression. I am less interested in that. What I am interested in is supporting Ukraine to conduct its own trials, supporting regional national authorities such as Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Moldova, to really investigate and prosecute these crimes, not to create a super international tribunal which will disappear into the Western capitals’ political conversation.

It’s going to be difficult to get hold of Russian officials, of Putin, of these hundreds of enablers of this crime of aggression and many other violations. It’s going to be more important to try and further these trials in their domestic settings such as Ukraine and those regional national authorities that try to do it. If we start to focus on an international tribunal which is not the ICC we’ll start to distract from those national efforts. That’s where we might achieve something.

Let’s not fool ourselves. International lawyers are very excited about how Germany has acted quite boldly and pursued universal jurisdiction on Syria and that’s a good thing. But what we really need to do is to support Ukraine to do it and hope for political change in Russia. The whole thing must be joined up not to create jobs for international lawyers but to create real accountability locally as much as is possible. Let’s support Ukraine to do it first.

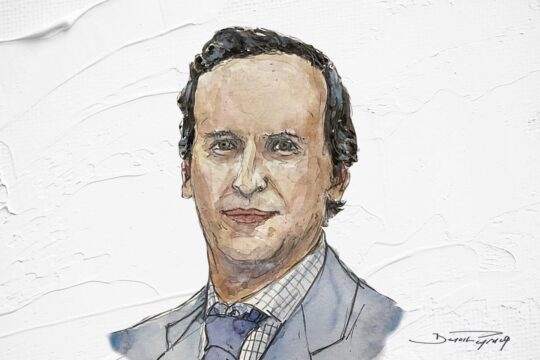

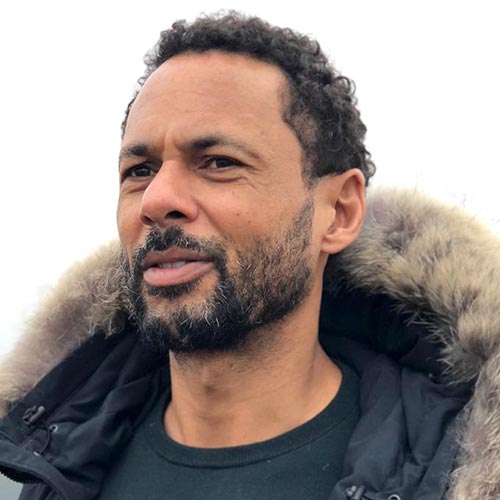

Wayne Jordash is the Managing Partner of Global Rights Compliance (GRC), a law firm and a foundation. Since 2015, GRC has worked with the Ukrainian Prosecutor General and civil society to support the investigation and prosecution of Russia's violations of international law in the occupied territories of Crimea and Donbass. Jordash has also been a defense lawyer before many international tribunals, including the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the Special Court for Sierra Leone.