A brief survey of news headlines from one week in late June 2015 reveals that, in Northern Ireland, the past is still very much in the present. Those headlines relate to the recovery of the bodies of two of the disappeared – victims who were murdered and secretly buried by republican paramilitaries during the conflict; a stark warning by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) Chief Constable George Hamilton that dealing with conflict-related atrocities is placing resource pressure on the organisation and putting public confidence in the PSNI at risk; and that one of the most controversial deaths of the conflict – that of Pat Finucane, a human rights lawyer murdered by loyalist paramilitaries in collusion with British state agents, will not be the subject of a public inquiry. These brief examples are indicative of the many unresolved questions of the Northern Ireland conflict.

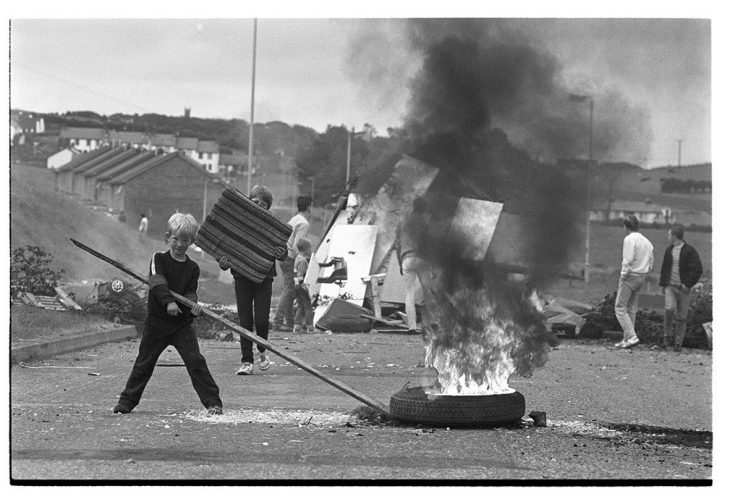

The Northern Ireland conflict, fought between loyalist and republican paramilitary organisations and the British state, began in 1968 and lasted over 30 years. During this period, approximately 3,700 individuals were killed, over 40,000 injured and tens of thousands displaced due to intimidation and political violence. The peace accord, the Belfast Agreement, was signed in 1998 by 8 of Northern Ireland’s main political parties and the British and Irish governments. While the Agreement acted as a blueprint for political and legal reform, including the release and reintegration of political prisoners, decommissioning of paramilitary weapons, reform of the police and criminal justice system and enhanced protection of human rights, it remained silent on the issue of truth recovery. Rather, dealing with the past was deemed too sensitive and potentially destabilizing for the embryonic political institutions. Sixteen years on, truth recovery has been piecemeal and the question of establishing a formal overarching truth recovery process has been the subject of ongoing political contestation. This article outlines the contours of this debate and argues that an overarching truth recovery process is required.

The Piecemeal Approach to the Past

As in other jurisdictions emerging from a period of conflict and human rights abuses, the reasons why Northern Ireland should ‘deal with’ its past have been well rehearsed even if they are not uncontested. They include promoting accountability; reaffirming the rule of law; responding to the needs of victims and survivors; challenging dishonest denial; and making known the range of forensic, personal and social truths about past conflict. In the absence of a formal truth recovery process, an array of truth-finding mechanisms have emerged, constituting what academic Christine Bell has characterized as the ‘piecemeal’ approach to the past. Four broad styles of intervention can be identified. First is the use of law as a recourse to truth and justice – typically through high profile public inquiries, such as the Saville Inquiry into the events on Bloody Sunday, 30 January 1972, when 13 civilians were shot dead by British Army paratroopers, but also through civil actions, private prosecutions and inquests in the coroner’s courts. Second is police-led truth recovery, including police-led cold case reviews by the Legacy Investigations Branch (LIB) within the Police Service of Northern Ireland and investigations into alleged historical police misconduct by the Office of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland (OPONI). Third, there has been a range of community-led truth recovery projects, including local storytelling projects and community inquiries. Fourth, there are a number of victim-centred initiatives in place, including the creation of an independent commission to help locate the remains of ‘the disappeared’ and the creation of the Commission for Victims and Survivors Northern Ireland to promote the interests of victims and survivors.

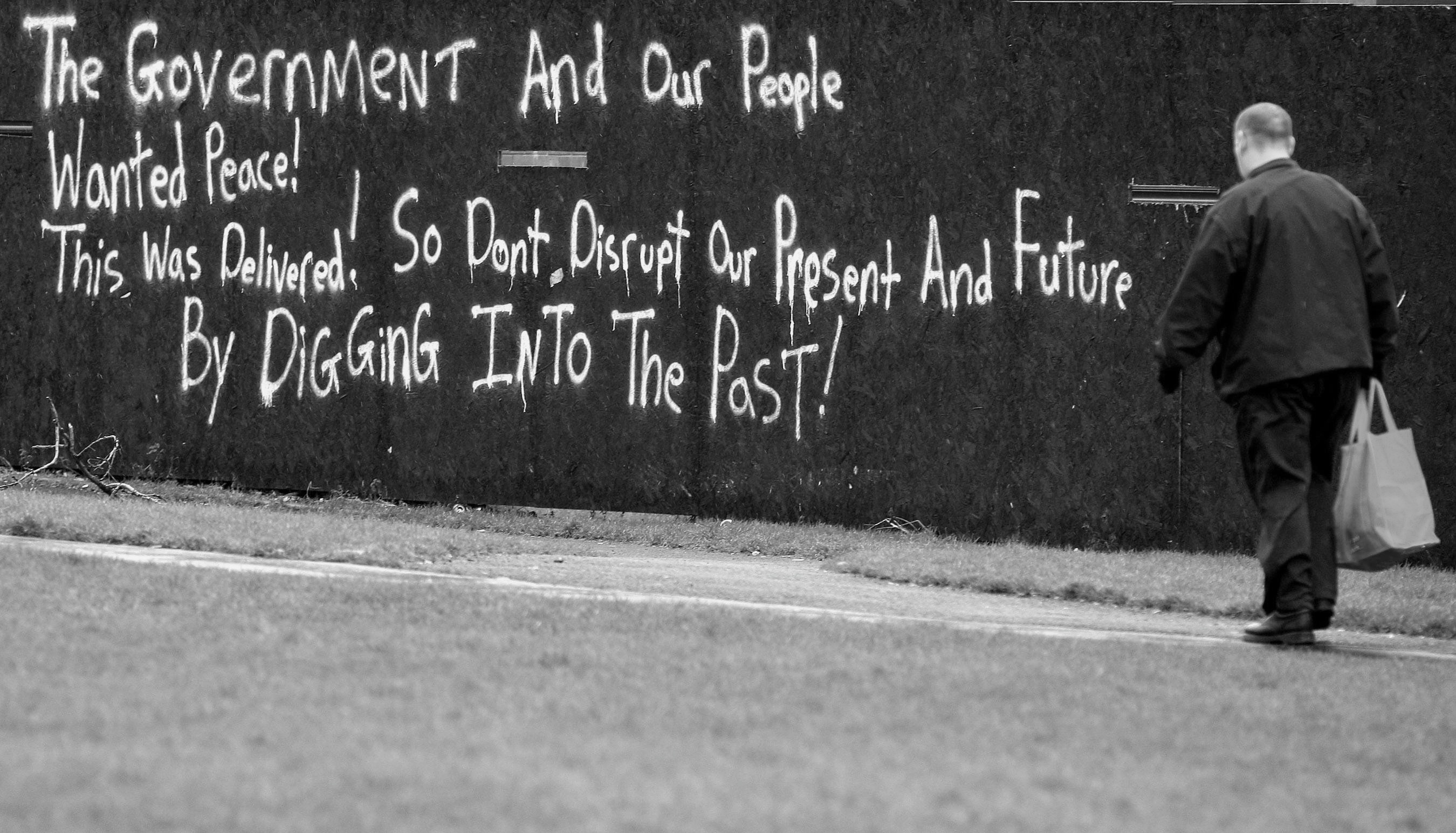

This disaggregated approach to the past is however, inherently limited. Individually, the mechanisms themselves have been found wanting. There has, for example, been strident criticism of the independence and impartiality of the policing approach to the past, while public inquiries, by nature, can only look at a limited number of cases. Inquests in the coroner’s courts have similarly been characterized by endemic delays and obstruction. Collectively, with the different mechanisms operating in isolation and often with a specific and narrowly defined remit, the current approach to the past cannot, for example, offer a full exploration of the broader context and consequences of the conflict and has created considerable ‘accountability gaps’. It is also unstructured, meaning that Northern Ireland is subject to a daily diet of past revelations and accusations which does little to promote political or social stability and can be individually retraumatizing for victims and their families. The unresolved nature of the conflict has also allowed the past and its truths to become a political weapon, with past atrocities often picked out and appropriated for political ends. Such tactics do little to promote social healing; rather, they perpetuate and reinforce hierarchies of victimhood and the sense that some victims receive more acknowledgement than others. Likewise, there are many victims who are falling between the gaps between the different mechanisms, receiving neither truth, justice nor an adequate response to their needs.

This disaggregated approach to the past is however, inherently limited. Individually, the mechanisms themselves have been found wanting. There has, for example, been strident criticism of the independence and impartiality of the policing approach to the past, while public inquiries, by nature, can only look at a limited number of cases. Inquests in the coroner’s courts have similarly been characterized by endemic delays and obstruction. Collectively, with the different mechanisms operating in isolation and often with a specific and narrowly defined remit, the current approach to the past cannot, for example, offer a full exploration of the broader context and consequences of the conflict and has created considerable ‘accountability gaps’. It is also unstructured, meaning that Northern Ireland is subject to a daily diet of past revelations and accusations which does little to promote political or social stability and can be individually retraumatizing for victims and their families. The unresolved nature of the conflict has also allowed the past and its truths to become a political weapon, with past atrocities often picked out and appropriated for political ends. Such tactics do little to promote social healing; rather, they perpetuate and reinforce hierarchies of victimhood and the sense that some victims receive more acknowledgement than others. Likewise, there are many victims who are falling between the gaps between the different mechanisms, receiving neither truth, justice nor an adequate response to their needs.

More broadly, it is clear that Northern Ireland remains far from ‘at peace’ with the legacy of its violent past. Rather, the divisions of the past are all too readily seen in the failure to deal with some of the most intractable ‘legacy’ issues including those relating to the display of flags in public places and the route, timing and nature of single identity parades and protests. Debates over who is to ‘blame’ for the conflict and a politically polarized struggle over so-called ‘innocent’ and ‘guilty’ victims continue to dominate politics and public discourse. At the societal and individual level the picture is equally bleak: it is often those communities which bore the brunt of violence that are now amongst the most socio-economically deprived areas of Northern Ireland. Suicide rates – particularly amongst young men – are growing, the prescription rate for anti-depressants is one of the highest in the world and trans-generational trauma is an increasing concern.

Establishing a formal truth process

Against this backdrop, there have been consistent calls, from victims and their families, victims groups, human rights NGOs and others, for a full examination of the past and the creation of a formal overarching truth recovery mechanism. The most recent initiative in this vein is the signing of the Stormont House Agreement (SHA) in December 2014. The product of cross-party talks, the Agreement is designed to break the log-jam on the outstanding issues of the peace process – finance and welfare, flags, identity, culture and tradition, parades and institutional reform (all ostensibly ‘legacy’ issues) and dealing with the past.

As regards truth recovery and dealing with the past, the Agreement provides for the creation of a number of bodies. If established, they will supersede the existing mechanisms and will effectively constitute a Northern Ireland specific truth commission, with the potential to overcome at least some of the limitations outlined above. In brief, proposed bodies and their remits are as follows:

- The Historical Investigations Unit (HIU) ‘an independent body to take forward investigations into outstanding Troubles-related deaths’.

- An Independent Commission on Information Retrieval (ICIR) ‘to enable victims and survivors to seek and privately receive information about the deaths of their next of kin’.

- An Oral History Archive ‘to provide a central place for people from all backgrounds to share experiences and narratives related to the Troubles’.

- An Implementation and Reconciliation Group ‘to oversee themes, archives and information recovery’.

Further work on the proposal that a pension be paid to the severely injured and the establishment of a comprehensive ‘Mental Trauma Service’ have also been recommended.

Potentials and Pitfalls

At the time of writing, legislation is being drafted on the legacy aspects of the Stormont House Agreement and it is expected that the relevant bill will be presented at Westminster in the autumn of 2015. However, much work remains to be done. The SHA is essentially an agreement based on bullet points – fleshing out the precise details of the legacy mechanisms is the outstanding task. It is also the space in which competing political interests are likely to clash. In this respect, Northern Ireland does not have a good track record. Two previous attempts to establish formal mechanisms to deal with the past – the Report of the Consultative Group on the Past in 2009, and a proposed agreement put forward by Richard Haass and Meghan O’Sullivan in 2013, disintegrated in political disagreement. It is immediately apparent that there are a number of potentially contentious areas that need to be worked out. They include whether former members of the security forces will be involved in the HIU – likely to be favored by unionist politicians given their historically close relationship, but considered by others to compromise the independence of investigations given that the security forces were an active participant in the conflict; the ability of the ICIR to offer robust guarantees of non-prosecution in return for information recovery; and whether the Oral History Archive can inspire confidence and trust in its ability to safely collect and house victims’ and survivors’ testimonies from across the political spectrum. A debate is also emerging on whether members of paramilitary organisations injured by their own actions will be eligible for the proposed pension payment.

These cautions notwithstanding, the provisions made in the Stormont House Agreement represent a vital opportunity to deal with the past in Northern Ireland. Political will, financial support, and commitment to implementation, openness and transparency are now required if this potential is to be realised.